Playing by ear is a great way to pick up songs easily and quickly. You can both do it with notes and chords, and it can be nice and easy or really hard. You’ll be able to start off with ease, but then it’ll take practice…

In this important guide, I’ll show you how to learn by ear through understanding how to recognise certain intervals.

If you’re looking to learn by ear, then this guide will help you out!

What Is Learning By Ear?

Learning by ear is essentially the process of learning a piece of music without any written music. It comes from the aural tradition of folk music, where melodies would rarely be written down, and people would learn by hearing, and then replicating music.

While in many cases, it can make learning music harder, it can also give a much more natural musicality to your playing. Think about it: playing from sheet music means you’ll be playing exact notes at exact rhythms like a robot; playing by ear means you’ll hear the subtle nuances of the performer and be able to bring these subtle rhythmic/melodic inflections to your own playing, making it more natural.

There are certain people who will be able to take a few shortcuts when learning by ear. A huge benefit to this would be if you happen to have something called perfect pitch. This where you can hear a note and know what it is without seeing it written down and without context. For example, you could hear the opening ‘E’ of Metallica’s ‘Enter Sandman’ and know it was an E straight away. Test this out yourself, and if you find you have this gift, everything we talk about below will become a lot easier. It’s also really helpful for tuning, as you’ll know when your guitar is in tune.

Another alternative is relative pitch, where you can understand which note is which, when in context with others. So if you hear an ‘A’, you can’t tell it’s an ‘A’ straight away, but as soon as you know you’ll be able to put there notes that follow it into context. This understanding of intervals will also be really helpful when learning everything below.

What Is The Process?

Melody

- Listen. Don’t worry about holding your guitar at the moment, just listen to the song and focus.

- First Note. This is the key part. If you don’t have perfect pitch, you’ll basically just have to do this through experimentation. You’ll be able to hear whether the note is high or low and roughly where it is, but pinpointing the exact note can only really come from trial and error.

- Second Note. This is where you’ll get your starting point for working out the melody. Use the interval training we’ll look at below to get used to hearing the way certain intervals sound and apply them to the track you’re learning.

- The Rest. Apply this to the rest of the notes in your melody.

- Rhythm. Rhythm is a bit easier to learn by ear as you can simply remember the sound of the melody you’re playing, and hit each note at the times you remember.

- Check. If the situation allows, check your playing against a recording of the song you’re learning. If it doesn’t clash, you’ve pulled it off. If you hear clashes, go back and see which notes you’ve gone wrong on.

Chords

- Listen. Don’t worry about holding your guitar at the moment, just listen to the song and focus.

- First Chord. This is the key part. If you don’t have perfect pitch, you’ll basically just have to do this through experimentation. You’ll need to understand the type of chord, which will often (but definitely not always) be determining whether the chord is major or minor (basically, does it sound happy or sad) and the root note.

- Second Chord. Use the interval training below like when working out a melody, but combine it with the understanding of chord types. Your major/minor understanding should be easy, but in certain case you’ll need to listen out for extensions to chords. You can do this using interval training too.

- The Rest. Apply this to the rest of the notes in your melody.

- Rhythm. Rhythm is a bit easier to learn by ear as you can simply remember the sound of the chords you’re playing. Most of the time this will be a strumming pattern, but you should also be paying attention to the way the chords are being played: funky, staccato, overdriven etc.

- Check. If the situation allows, check your playing against a recording of the song you’re learning. If it doesn’t clash, you’ve pulled it off. If you hear clashes, go back and see which notes you’ve gone wrong on.

Interval Training

Interval training is used to get used to how certain intervals sound when in context. I’ll show you this through famous melodies you can use as a reference point, as well as giving examples of how to play each interval on a standardly tuned guitar.

-

- Unison: This is definitely the easiest interval you’ll come across as it is literally just the same note. This shouldn’t take any working out, as once you’ve heard the first note, the second will simply be exactly the same.

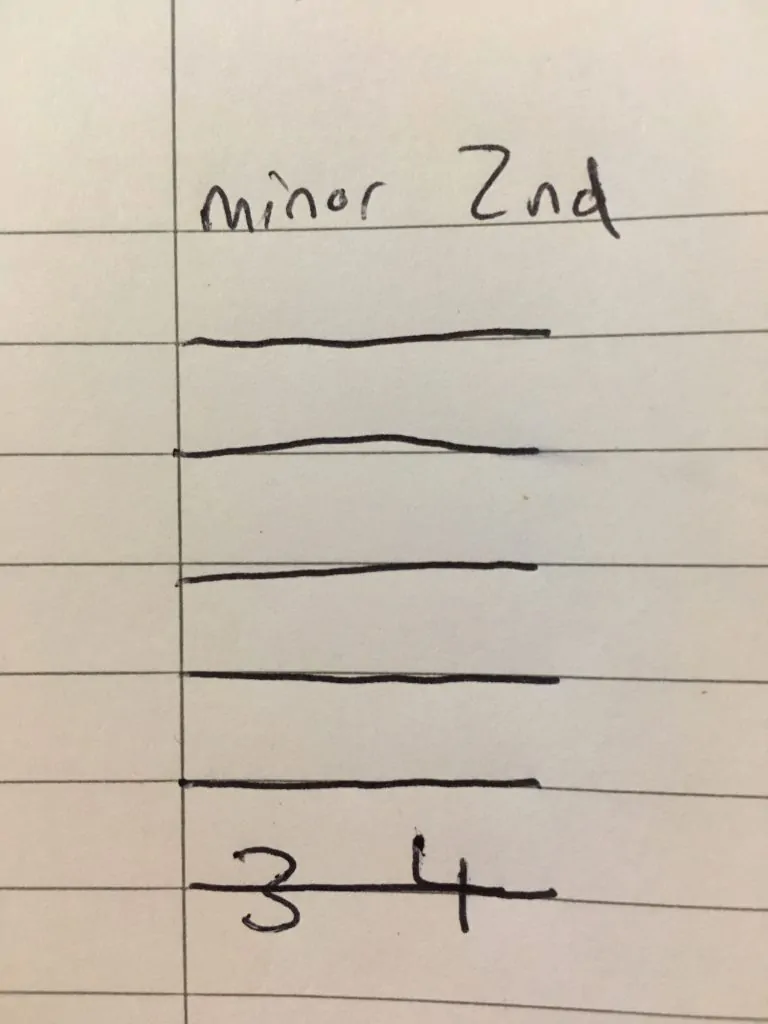

- Minor 2nd: A minor second is movement of one single semitone. It’ll rarely come directly after the tonic note, as this wouldn’t be diatonic to the key, but it could appear here if using the Phrygian mode. A listening example of an ascending minor 2nd can be seen in the theme to Jaws; while a descending example comes from Beethoven’s ‘Fur Elise’. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

- Major 2nd: This movement of one tone is much more common in music, and there are countless melodies that use them throughout. A tonic could easily move to the major 2nd, as that would be diatonic. An example of an ascending major 2nd comes from the classic tune of ‘Happy Birthday To You’; while descending can be shown in ‘Mary Had A Little Lamb’. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

- Minor 3rd: The minor 3rd (or in some cases, augmented 2nd [they sound the same but appear in very different contexts]) is my personal favourite interval in music. It’ll appear diatonically from the tonic when in a minor key if you move up by one tone and a semitone. The example I always use is Axel F’s ‘Crazy Frog’ when ascending; while descending examples come from The Beatles’ ‘Hey Jude’. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

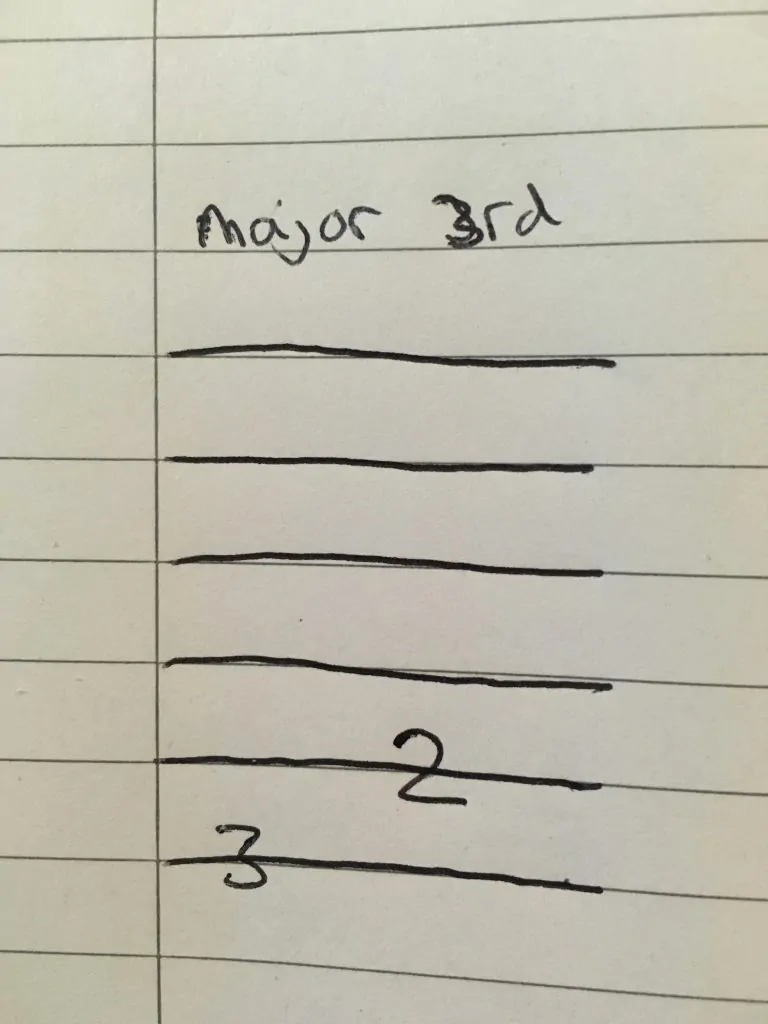

- Major 3rd: Major 3rd intervals present themselves diatonically in a major key when moving from the tonic. It is a movement of 2 tones. The old tune of ‘Oh When The Saints’ opens with an ascending major 3rd; while ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’ has a descending major 3rd that’ll help you get used to hearing the interval. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

- Perfect 4th: When you move from the tonic by 2 tones and a semitone, you’ll reach the perfect 4th interval. This appears in major and minor keys, as well as most modes. The opening leap from the Harry Potter theme is built around an ascending perfect 4th interval; while ‘Oh Come All Yee Faithful’ moves down a perfect 4th after the opening unison interval. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

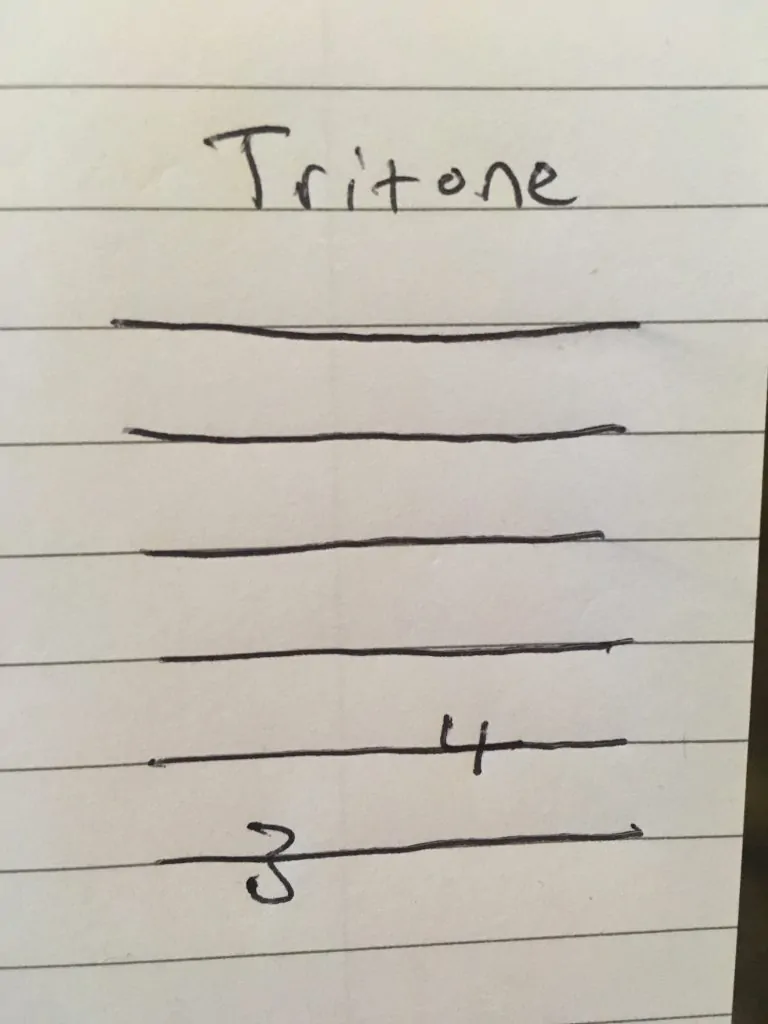

- Tritone: A tritone (also known as an augmented 4th, diminished 5th or the devil’s interval) is the exact halfway point between an octave, and a semitone less than a perfect 5th. It has a large amount of dissonance, and is particularly hard to sing but is a defining feature of the Lydian mode. The opening chant of The Simpsons theme is a tritone; while Black Sabbath’s self-titled first song descends by a tritone after the initial octave leap. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

- Perfect 5th: A jump of a perfect 5th is a simple interval that appears in almost every scale and most chords. ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’ opens with an ascending perfect 5th; while the theme to The Flintstones opens with a perfect 5th descent. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

- Minor 6th: Minor 6th leaps are relatively rare in music as they are quite jarring, large intervals made up of a semitone more than a perfect 5th. Scott Joplin’s ‘The Entertainer’ has a very distinctive minor 6th ascension that you’ll be able to use as a reference point when learning by ear; while the “call me” of Carly Rae Jepsen’s ‘Call Me Maybe’ is a descending minor 6th. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

- Major 6th: The major 6th is probably even more rare, and hence appears in relatively few well known pieces of music, unlike that shown above. ‘My Bonnie Lies Over The Ocean’ has a distinctive jump of a major 6th; while ‘Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Seen’ gets a major 6th descent into the word “nobody”. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

- Minor 7th: Minor 7th intervals are just a tone away from being a pure octave, so it’s often quite a dissonant jump which appears in the minor scale. ABBA’s ‘The Winner Takes It All’ shows off the large leap with ease; while Herbie Hancock’s ‘Watermelon Man’ has a large minor 7th descent. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

- Major 7th: A major 7th is essentially a reverse minor 2nd, as it is one single semitone away from an octave interval. It’s use often leads up to an octave, with the example of ‘Take On Me’ by A-ha doing exactly that; while one of the only examples of it being used as a descent comes from Cole Porter’s ‘I Love You’. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

-

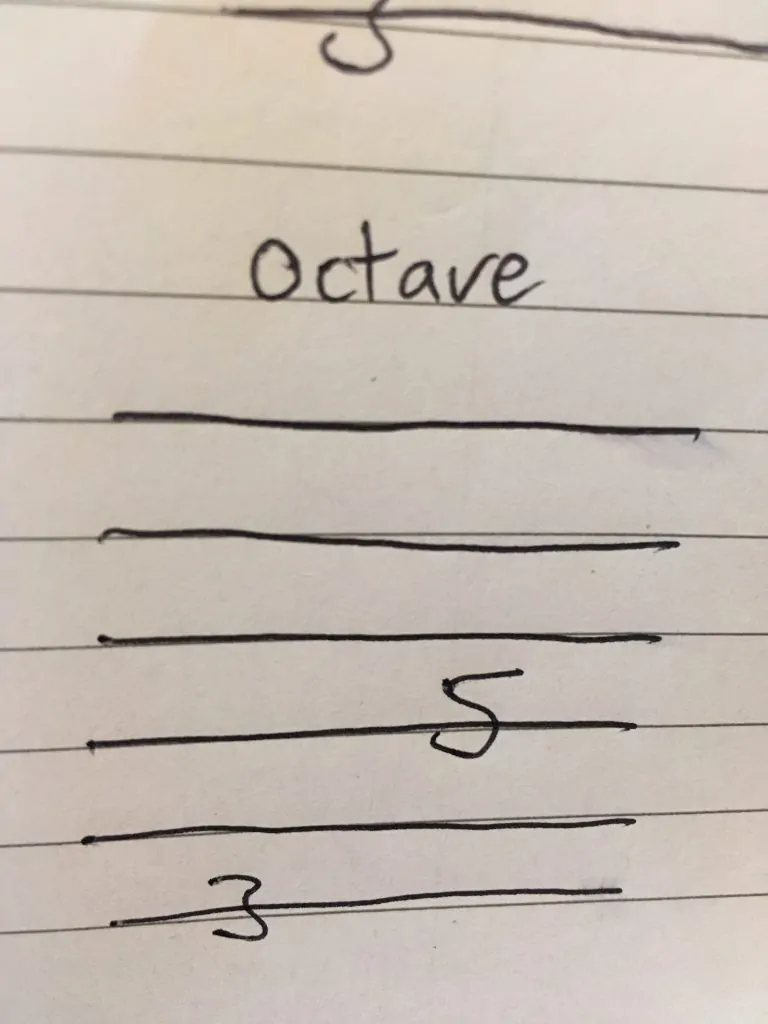

- Octave: Finally, we’ve reached a common interval once again. An octave simply repeats the same note, but up a whole octave (AKA 12 semitones). ‘Somewhere Over The Rainbow’ opens with this huge jump, while the descent from ‘Willow Weep For Me’ is also an octave. Playing the interval based on the starting point of a ‘G’ on guitar is shown here.

Trying It Out

Firstly I’ll guide you through a simple riff that any beginner guitar player should know: Deep Purple’s ‘Smoke On The Water’.

- Listen: Listen to the track here.

- First Note: Do a bit of trial and error to work it out (technically two notes are playing at once here, but just using one of them will work and sound fine for now).

- Second Note: Now use the interval training above to see what the first interval you’ll be moving up by is, and then determine how many frets that means you’ll have to jump.

- The Rest: Keep using the interval training to work out the rest of the notes in the melody. They aren’t too hard but you’ll have to both ascend and descend.

- Rhythm: This should be nice and easy, as all you’ll need to do is listen to the piece and determine how long you’ll be staying on each note for.

- Check: Try and play along with the song to see if your notes are clashing or not.

Dan is a music tutor and writer. He has played piano since he was 4, and guitar and drum kit since he was 11.

He plays a Guild acoustic and a Pacifica electric. He has been sent to many festivals and gigs (ranging from pop to extreme metal) as both a photographer and reviewer, with his proudest achievement so far being an interview he has with Steve Hackett (ex-Genesis guitarist).

He ranks among his favourite ever guitarists, alongside Guthrie Govan, Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, David Gilmour and Robert Fripp. His favourite genre of music is progressive rock, which he likes to use as a reference point in my teaching, thanks to its huge complexity in structure, rhythm and harmony. However, he is also into a lot of other genres including jazz, 90’s hip-hop, death metal and 20th century classical music.