Alongside the notes you play, the rhythms you use to play those notes are what makes the tune you’re playing recognisable! Time signatures (also known as meters) are the first thing you need to get your head around, and that’s where we come in!

In this important guide you will learn:

- What a time signature is

- What the most common time signatures are

- The idea of compound time

- Some tips on counting time signatures (with examples)

- How to work out what time signature a piece is in

- And we’ll take a look at a few more advanced time signatures

If you’re struggling to understand time signatures or just need a helping hand, then you’re in luck.

First things first

- Note values. A whole note (also called a semibreve) is 4 beats long. A half beat note is 2 beats long, a quarter note is 1 beat long, an eighth note is half a beat long and a sixteenth note is a quarter of a beat long. The pattern carries on like that, but don’t worry, we won’t need anything more than a sixteenth today. J

- Stay in time. Understanding tempo and how to tap along with a song at the right tempo is key to being able to understand time signatures.

- Barlines. A bar is a way of subdividing music. They are small sections within a tab (or musical score), which will be separated by a thin black line to tell you where to start counting the time signature from the beginning again.

What is a time signature?

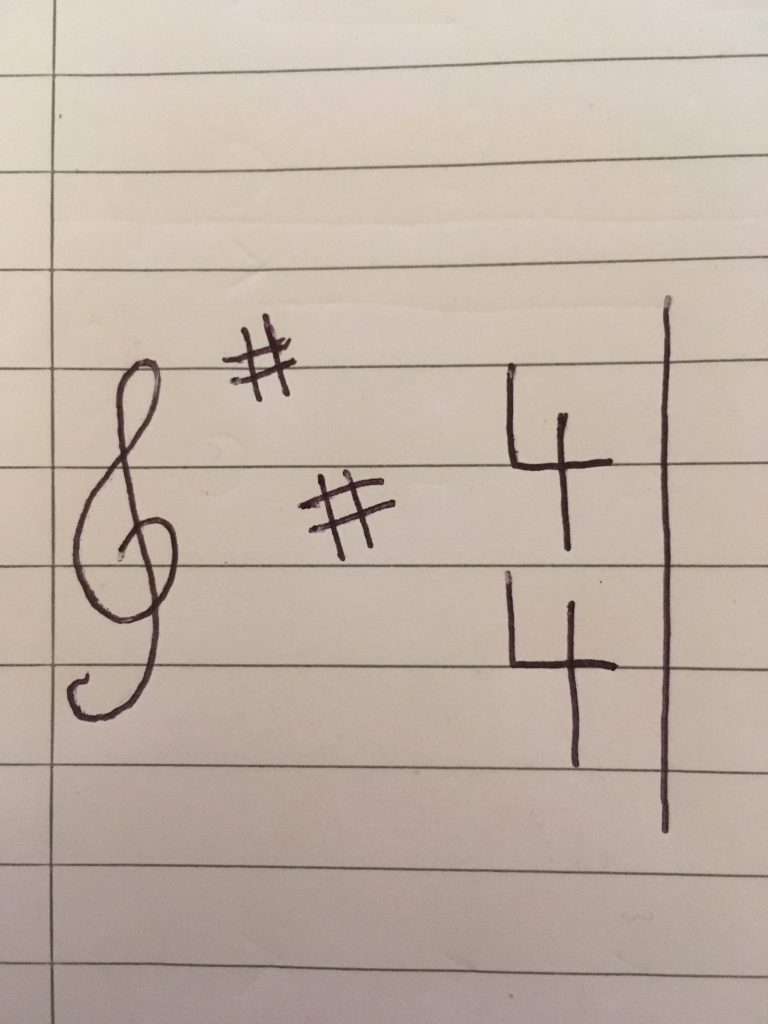

In musical notation, the time signature is one of the first things you’ll see. It’ll be right at the beginning of each line, just after the clef (the symbol you’ll see at the start of a piece of notated score, but not tab) you’re playing in and any key signature that might be being used. If you’ve never seen one of these before, it’ll just look like a number sitting on top of another number.

Showing where the time signature will be at the beginning of a piece.

The number at the bottom will be a 1, 2, 4, 8 or 16 (bear in mind that it is possible to keep this pattern going forever, but it’s unlikely you’d ever come across anything higher than 16) and the number at the top could be anything (though again, you’d very, very rarely see anything above 20). These numbers are there to tell you how many beats there are in a bar, and of which length each beat is.

- The bottom number is telling you the note value each bar will be using.

- The top number is there to tell you how many of each note value is heard within each bar.

This means that a time signature of 4/4 would have 4 quarter beat notes per bar. A 2/4 time signature would have 2 quarter beat notes per bar; a 3/2 time signature would have 3 half beat notes per bar; a 7/8 time signature would have 7 eighth beat notes per bar. Make sense? Take a look at this table to help you understand how long each note value lasts- it’s really important.

A table showing how to form the bottom number in a time signature, and how to understand the concept.

Basically, if you’re in 4/4, you’re going to be counting to 4 a lot, if you’re in 3/4, you’ll count to 3 a lot. You’ll get the hang of it really quickly, but…

We can make this simpler

A lot of the numbers you see in a time signature are much more likely to appear than others, with simple time referring to these common, easy to understand time signatures. Think back to the last time you made something up on guitar- it was probably in common time. If I had to guess, I’d say 4/4, which looks like this.

A 4/4 time signature.

Let’s take a look at some simple time signatures!

Common Time Signatures

Now that we know how time signatures are formed, we can have a look at some of the most common ones you’ll come across, especially as a beginner.

- 4/4: 4 quarter notes per bar. This is the most common time signature in popular (western) music. In fact, I challenge you to take a look at the charts right now and find me a song that you don’t tap along to in measures of 4 beats. Let’s have a look at some examples: Ed Sheeran’s ‘Shape Of You’ and Eminem’s ‘Not Afraid’. I guarantee that you can find 1000 more.

- 3/4: 3 quarter notes per bar. Another quite common signature, often attributed to waltz music, but also found in a lot of pop. While it’s hard to find this time signature crop up in ‘four to the floor’ dance music, there are still a number of hits with 3 beats to a bar: Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Manic Depression’ and Jay-Z’s ‘My 1st Song’.

These two are a guitarists bread and butter- nice and easy to recognise, learn and compose with. J Below, things start to get a little more complex.

- 2/4: 2 quarter notes per bar. 2/4 is another interesting time signature, as it is rarely used exclusively in a song, sometimes it will only be used for one bar, during a piece that is mostly in a different time signature. Take Outkast’s ‘Hey Ya’ for example. When Andre 3000 reaches the “hey” of the chorus, start tapping out this pattern in time with the song: (1, 2, 3, 4), (1, 2, 3, 4), (1, 2, 3, 4), (1, 2), (1, 2, 3, 4), (1, 2, 3, 4). Notice that cheeky bar of 2/4? Me neither… at first.

This example actually raises a key point. Time signatures can change throughout a piece. One minute you could be playing in 4/4, and the next be in 3/4. Or you could have a piece in 2/4, and suddenly be presented with a bar of 5/8. So be ready.

- 2/2: 2 half notes per bar. This is where things get a bit more ambiguous. 2/2 is a lot less likely to appear in popular music, and as you may have guessed by now, could be a little hard to recognise. Most 4/4 meters can be counted in half time, simply emphasising every other beat (instead of every beat) and creating a pseudo-2/2.

- 6/8: 6 eighth notes per bar. A bit like 2/2, 6/8 can be slightly ambiguous, as you could count it as 2 sets of 3 beats or 3 sets of 2 beats. This makes it confusingly similar to 2/4, or 3/4, so we need to understand a new concept: compound time.

What is compound time?

Compound time essentially takes meters that could have each beat divided into 2 (like 4/4 and 3/4) and makes them divisible by 3.

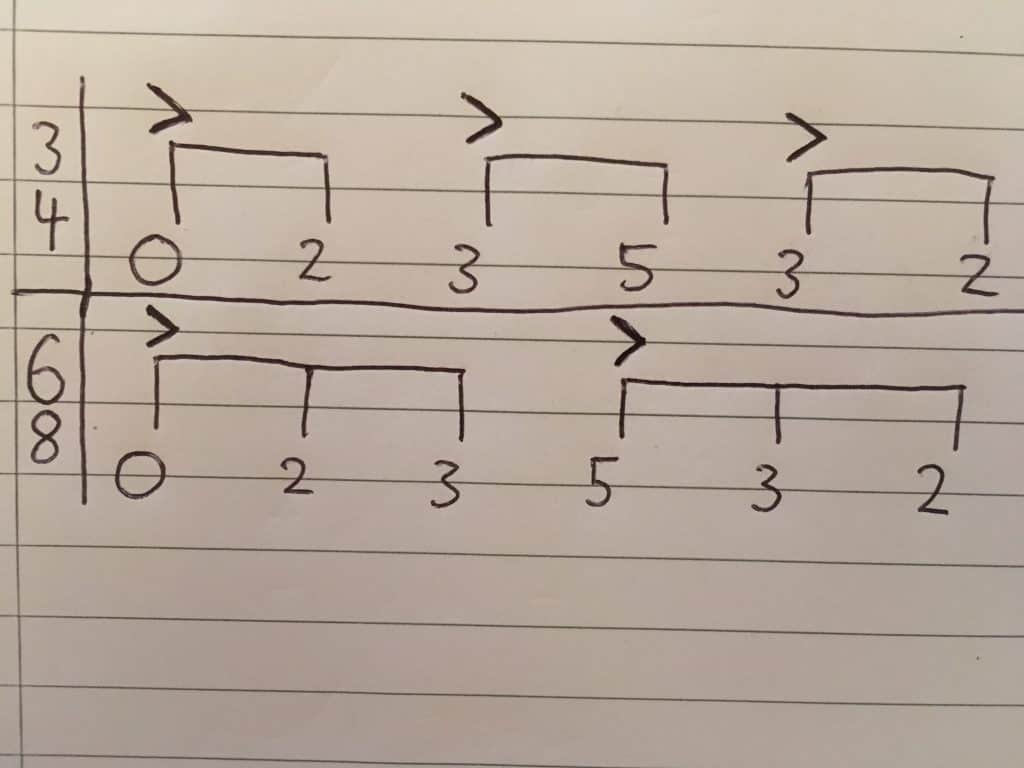

The best way I can show this is by comparing the way you’d emphasise (often using an accent, which looks like this: >) the beat in a bar of 3/4, with the way you’d emphasise the beat in a bar of 6/8, if both sets of notes were all eighth notes. Bold represents emphasis, with an underline strengthening the emphasis even further.

- 3/4: One and Two and Three and.

- 6/8: One two three four five six.

Comparing a 3/4 time signature with 6/8, based on the placement of accents.

See how they the same pattern, but the different accents mean they are different time signatures?

First of all, notice the ‘and’ when counting in 3/4. These represent the eighth note beats that fall in between the quarter note beats, which are put into a 3 beat grouping that emphasises all 3 beats in the bar.

This ‘and’ is dropped when counting in 6/8, as the eighth note pattern shown in the time signature already implies the use of eighth notes. This divides the bar into a 2 beat grouping, with emphasis on the first and fourth eighth note.

Despite these differences in emphasis, the patterns would last exactly the same amount of time, but it is the pattern of emphasis that determines the time signature.

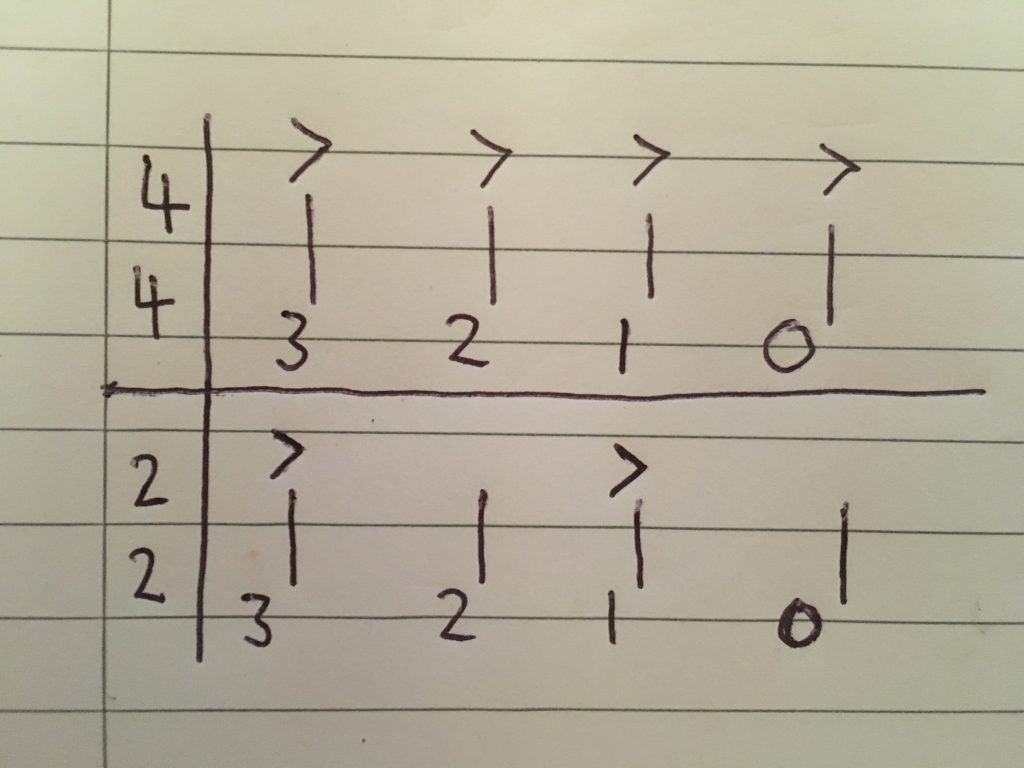

In a bar of 4/4, there will normally be a strong accent on each beat, and you could count out loud in groups of 4 quarter notes.

However, even if you hear a note played on each beat, that doesn’t mean it’s being emphasised. This bar of 2/2 below could be counted in 4/4, but due to the nature of the emphasis it would make a lot more sense for groups of 2 half notes.

Comparing a 4/4 time signature to 2/2, with the use of accents.

You can use the same knowledge to understand other time signatures. 9/8 for example, is counted in a pattern of 3 groups of 3 eighth notes, rather than the 3 groups of 2 eighth notes that comes from 3/4.

Let’s try and put this into practice

- The Animals- House Of The Rising Sun

This track is a great example as it’s nice and simple on guitar, so you can form it using the simple chords you’ve already picked up.

Before I tell you the time signature, have a go on your own to see if you can count it.

I’ve got a few handy tips if you can’t get it straight away:

- Listen out for chord changes. Often (and certainly in this case) chord changes will correspond with each bar.

- Tap along in time to find out how many divisions there are within the bar. This will at least help you to narrow it down to a few options.

- Then to find out exactly what’s going on, listen for where the emphasis is. Is it in 2 groups of 3 or 3 groups of 2 beats? (or something else… but we’ll get to that later).

For this track, our time signature is 6/8. Notice how each bar is made up of 1 chord, separated into 6 eighth notes. The emphasis is on the ‘one two three four five six’ pattern, making this distinctive meter stand out.

Use the same tips to try and work out this time signature:

- Mumford & Sons- I Will Wait

Another track that you’ll be able to get the hang of chord-wise pretty early on, but can you work out this time signature?

There is a nice helping hand going on throughout, as the bass drum hits on every quarter beat. They might as well be clapping your hands for you! Beyond this, we can rule out any triple meter as it just doesn’t fit (try and count this in 3/4- you’ll see what I mean) and then we’re down to the final question- is it 4/4 or 2/4?

As the chord often changes every 2 beats, the emphasis sometimes comes every 2 beats. We can suggest that this one is in a 2/4 time signature. Although, it is pretty ambiguous and you wouldn’t be wrong to suggest 4/4.

Ready for a tricky one?

- Pink Floyd- Money

Taken from ‘Dark Side Of The Moon’ this track has sealed its place in rock history, but something pretty special is going on with its time signature.

- The chords change in an uneven pattern of 3 quarter notes, then 2 quarter notes, then 2 quarter notes.

- The emphasis comes alongside the chord changes, giving a pattern of 3+2+2, which gives us a total of 7.

- The fact that most notes fall on the beat, with no filler in between, means we can fairly confidently say that this piece follows a pattern of quarter notes (so the bottom note of the time signature will be a 4).

This creates 7/4 time, something quite complex and relatively rare, but let’s take a look anyway!

Complex time signatures

Complex time signatures.

This is where things get weird.

An understanding of this aspect of music theory is essential for your development as a guitarist, though a beginner will rarely encounter such complexity.

If you feel like checking back later when you’re more comfortable with the basics, then put your new found understanding of time signatures to the test with our ’10 Easy Songs On Guitar’ or maybe even try to ‘Learn Guitar Scales’ in a few different time signatures.

Ready?

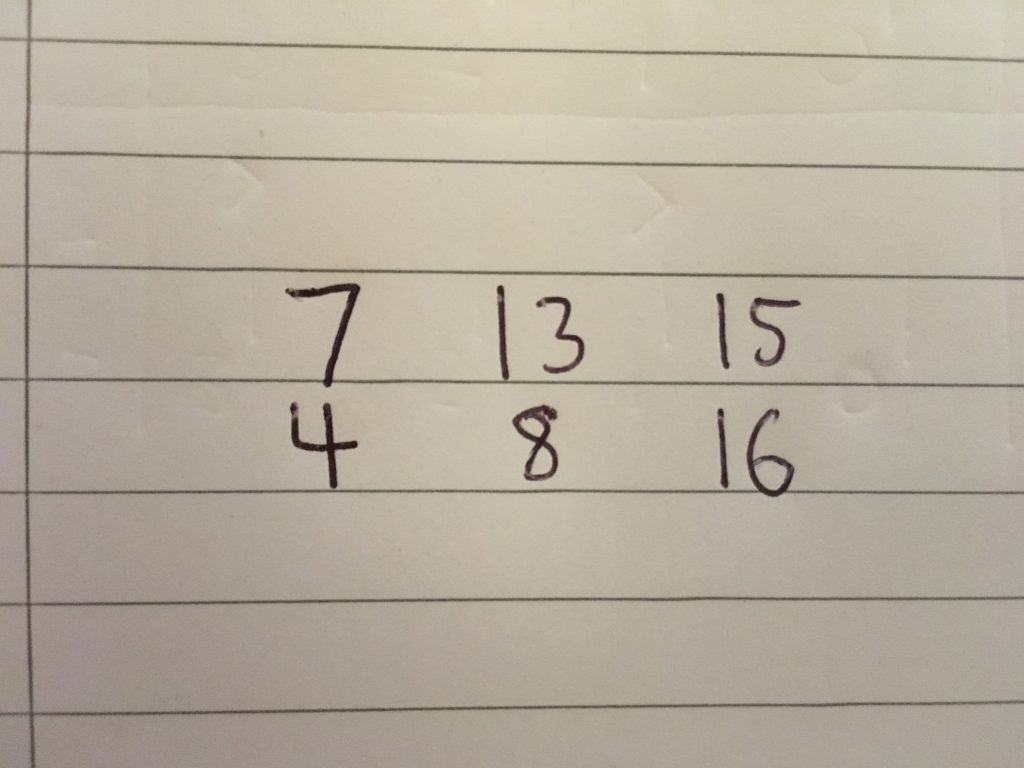

So if you remember everything we’ve just done, you’ll know exactly how many beats are in a bar of 5/8 (5 eighth notes) or a bar of 13/16 (13 sixteenth notes). In terms of being able to read music that uses these time signatures, that’s pretty much all you’ll need to know.

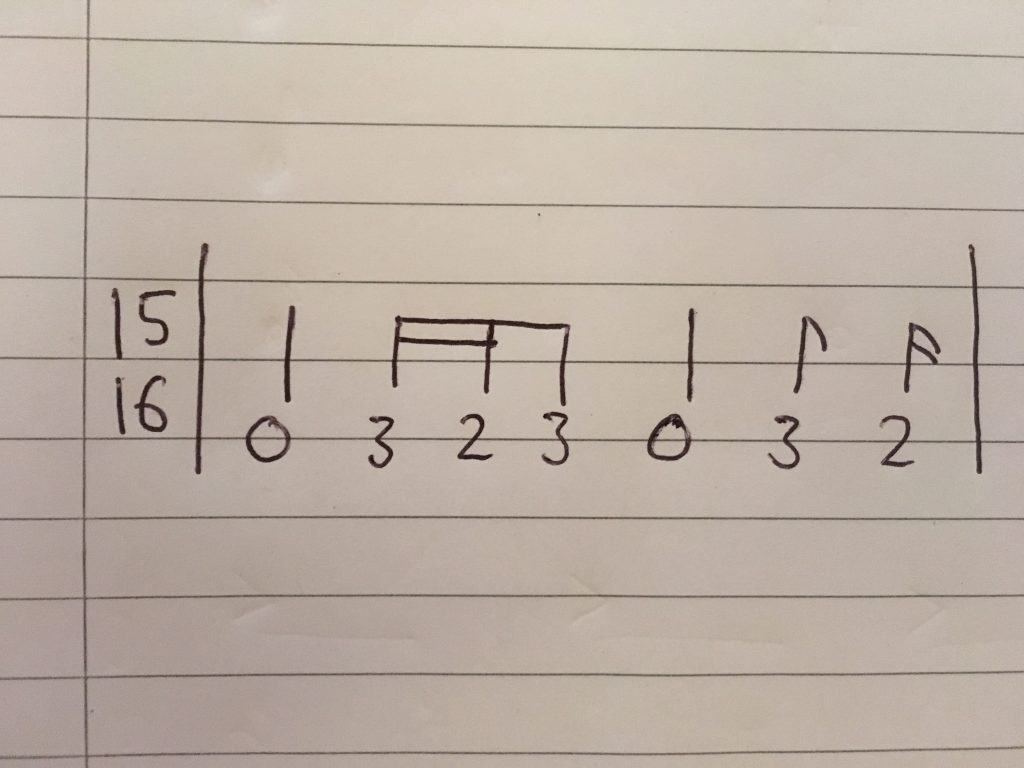

This melody for example, includes 2 quarter notes, 2 eighth notes and 3 sixteenth notes, which works out to form a 15/16 time signature.

A melody in a 15/16 time signature.

A few tips for playing in complex time signatures:

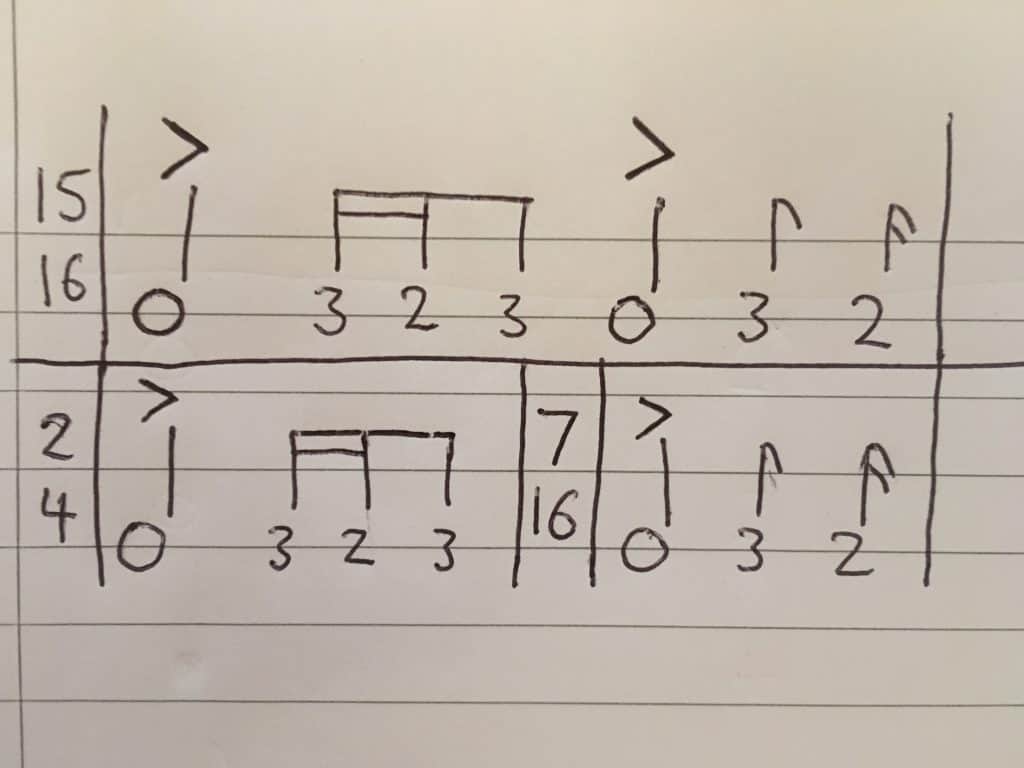

- Look out for accents and emphasis. Most pieces written in/using bars of complex time signatures will show you exactly how they should be broken down in terms of emphasis, through the use of accents.

You could view these as individual bars and follow the specified accents or approach by dividing it up into mini time signature changes based on where the accents are.

Deciding whether to use accents or seperate time signatures when playing using complex meter.

Both options would give the same sound, just approach it with whatever technique feels more natural.

- Practice with a metronome. Starting out on a piece which uses complex time signatures is always tricky, so get used to the rhythmic pattern by using a metronome with the setting you need. Time signatures go together with tempo to set the rhythm of the piece, so make sure you’re using the right tempo too. There are many free metronome apps available.

- Check your strumming pattern. Make sure to take our lesson on ‘Learning To Strum A Guitar’ so you can use the techniques you’ve picked up to adapt your strumming technique based on the time signature you’re playing in.

Check out this video on Dream Theatre’s ‘Dance Of Eternity’ (widely regarded as having the most time signature changes of any song). It shows a bit of everything we’ve covered in this guide, from how the time signatures change alongside accents/emphasis, as well as guiding us through the different, often very complex, time signatures. Don’t worry if it’s a bit baffling at first- I’m still wrapping my head around it too!

A final summary:

- The top number is how many beats, the bottom is what type of beat.

- Time signatures can change. Be on the lookout!

- When listening for a time signature, chord changes might help.

- Check where the accents are, and when playing, make sure to accent where necessary.

- Time signatures can be ambiguous! Be careful!

Dan is a music tutor and writer. He has played piano since he was 4, and guitar and drum kit since he was 11.

He plays a Guild acoustic and a Pacifica electric. He has been sent to many festivals and gigs (ranging from pop to extreme metal) as both a photographer and reviewer, with his proudest achievement so far being an interview he has with Steve Hackett (ex-Genesis guitarist).

He ranks among his favourite ever guitarists, alongside Guthrie Govan, Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, David Gilmour and Robert Fripp. His favourite genre of music is progressive rock, which he likes to use as a reference point in my teaching, thanks to its huge complexity in structure, rhythm and harmony. However, he is also into a lot of other genres including jazz, 90’s hip-hop, death metal and 20th century classical music.