Working off of tabs is perfectly fine, but if you want to level up a bit or you’ve developed an interest in classical guitar, sheet music is a good thing to learn. It’s not that you only find classic guitar pieces in guitar sheet music, you do find it in tabs too. But this is a nice transferable skill to develop.

Looking at sheet music for the first time can be overwhelming. It just looks like a bunch of lines and symbols, and French or Italian words. But once you get to know what each symbol means and how the lines and spaces work, it becomes as easy as reading a book.

It takes time to get there and most importantly, consistent good practice. In order for your brain to send the messages to your fingers to play the notes you’re reading, you’ll need to practice on your guitar too. You’ll need a bit of theory, don’t worry, just the basics, before you will fully understand what’s going on.

How to Read Guitar Sheet Music

Technically, it’s just sheet music, although what you find for guitar may be specifically written for guitar. But you can play any sheet music on a guitar. Well, some of the notes for brass instruments and woodwinds, organs, and even stringed instruments played with a bow are longer than the guitar can manage. But most pieces and songs can be played on the guitar if they take your fancy.

Naturally if you find some music and there are markings for vibrato or bends, it’s for a stringed instruments. Piano sheet music, for example, won’t have those markings since the piano can’t do those things.

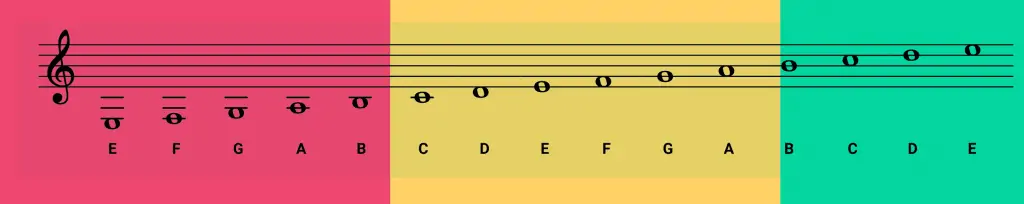

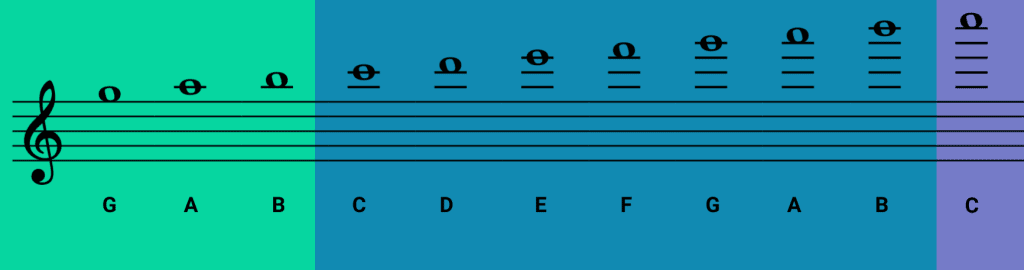

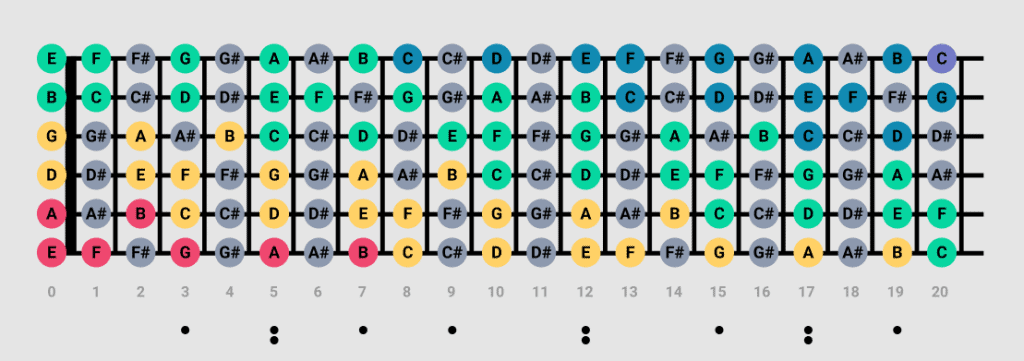

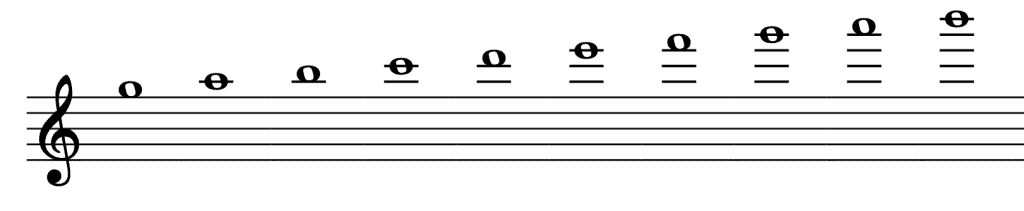

That said, let’s get into how to know which notes are where on the guitar. You can follow the notes linearly along the strings to match them to the notes on the staff.

- The sharps are included on the diagram of the fretboard, but note that the notes on the staff aren’t sharp or flat unless the key signature indicates that or there are specific accidentals.

To understand all that, be sure to check out the basic theory section.

The Guitar Fretboard Notes in Relation to the Staff

Some Basic Theory You Need to Know to Read Music Effectively

Below, you will find the basics that are an important part of reading music and understand what you’re playing fully. If you know a piece or song, it’s not hard to look at the notes and just play it properly because you have the timing of all the notes in your head. But for new pieces of music, you need to understand the note and rest values.

To add depth and emotion to your music, ornaments and dynamics are vital. Here’s what all those things look like.

Note Values

I’m going to start here since this is just as important as knowing what note to play. The value tells you how long to hold the note:

(Breve or Double Whole Note): 8 (rare)

(Semibreve or Whole Note): 4

(Minim or Half Note): 2

(Crotchet or Quarter Note): 1

(Quaver or Eighth Note): 1/2

(Semiquaver or 16th Note): 1/4

(Demisemiquaver or 32nd Note): 1/8

(Hemidemisemiquaver or 64th note): 1/16 (rare)

(Semihemidemisemiquaver or 128th Note): 1/32 (very rare)

I just had to include the crazy quaver notes. There is an even rarer quaver note, the demisemihemidemisemiquaver. Say that fast 5 times! As you may have guessed, it’s a 256th note and counts 1/64.

But don’t stress too much, I popped them in there more for fun. Quavers and semiquavers are pretty common, and now and then you’ll come across a demisemiquaver, but the others are very rare. So you won’t have to sit there counting tails.

Rest Values

Another important thing to know is the rest values that correlate with the aforementioned note values. Rests indicate that you stop playing for a certain count:

(Semibreve Rest or Whole Rest): 4

(Minim Rest or Half Rest): 2

(Crotchet Rest or Quarter Rest): 1

(Quaver Rest or Eighth Rest): 1/2

(Semiquaver Rest or 16th Rest): 1/4

(Demisemiquaver Rest or 32nd Rest): ⅛

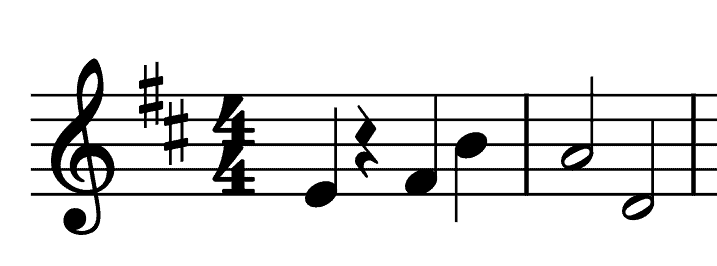

Time Signature

The time signature indicates how many beats are in a bar. Most of the time, the bottom number will be 4, although you will also find 8. More rarely, you’ll find bigger numbers. The bottom number indicates crotchets in the case of a 4, and quavers in the case of an 8. The number at the top indicates how many beats is needed in that bar to equal the beats at the bottom.

4/4 (common time, sometimes written as a C): 4 beats in a bar, e.g 4 x crotchets or 2 minims

3/4 (Waltz): 3 beats in a bar, e.g 3 x crotches or 1 x minim and 2 x crotchets

2/4: 2 beats in a bar, e.g 4 x quavers or 1 x minim

6/8 (like a waltz with a swing feel): 6 beats in a bar, e.g 6 x quavers or 3 x crotchets

You can have different combinations, but the note values have to match the top number. Remember, your rests count as beats too.

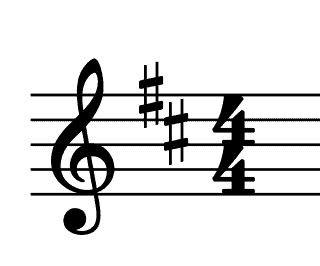

Key Signatures

The key signature is written next to the treble clef which is the clef guitars use.

For the most part, guitar music deals with keys that have sharps, but you will also find keys with flats. Knowing the key you’re playing in is important so that you don’t miss which notes are sharp or flat and can play along with others.

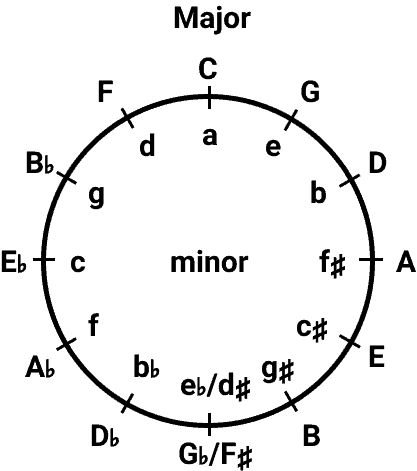

My favorite tool for this is the Circle of Fifths. Once you understand how it works, it’s as simple as memorizing the positions of the keys around the circle. You can also keep a picture up or keep it on your phone or just Google it if you need to and know in seconds what the key is.

Look at the right-hand side of the circle like a clock and the left-hand side as the mirror image. 12 o’clock has zero sharps or flats. Then 1 o’clock indicates one sharp, as does the 11 o’clock position, but for flats. You just carry on like that.

Keys don’t change, they always have the same number of sharps or flats. So you just need to remember where they are on the clock. You will be able to tell from your sheet music how many sharps or flats is in the piece.

The sharps and flats always follow the same order when written in the key signature. You can use these rhymes to remember it:

Sharps: Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle

Flats: Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles’ Father

Also note that E# is in fact F and that B# is in fact C. Fb is E and Cb is B. These are the only exceptions, but they need to be written as E#, B#, Fb, and Cb to be read on the staff.

Ties, Slurs, and Dots

Dots

I’ll start with the dots. If you see a dot next to a note, this means, you hold it for an additional half of the note.

For e.g.

. = 3

A dot under a note means to play staccato (sharply detached).

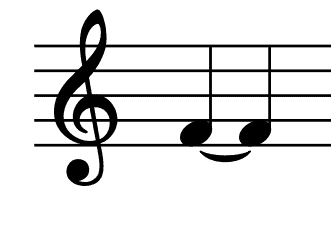

Ties

Ties mean you have to hold the note twice as long or as long as its value along with the note it’s tied to’s value.

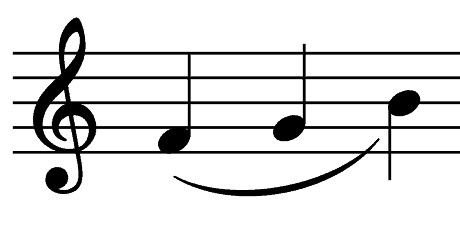

Slurs

Slurs look almost like ties but they function differently. Rather, they have you play multiple notes one after the other according to their note values in a smooth manner. You may also see the term legato which means to play smoothly.

Connected Quavers

♫ ♬

You’ve probably seen this at some point. This just a means of grouping together quavers, semiquavers, etc within a bar. You play each note, and they usually sound fairly quick because the note values are short. But you don’t need to do it in a staccato manner unless indicated on the music.

Dynamics

For a piece of music to sound like something more than just notes, dynamics are important. By this I mean going louder or softer.

Crescendo (Getting louder gradually)

Decrescendo (Getting softer gradually)

These two symbols that are kind of like greater than and less than signs are written at the bottom of the staff and will span the notes that you need to build the volume on.

You may also see the following, although most often they don’t come with the above dynamic markings

p: Piano (Quiet)

pp: Pianissimo (Quieter as in more quietly)

ppp: Pianississimo (Very quiet)

f: Forte (Loud)

ff: Fortissimo (Very loud)

fff: Fortississimo (Very very loud)

Ornaments

Because it’s not just dynamics that bring depth and emotion.

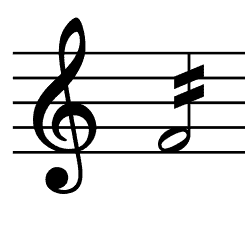

Tremolo

This is when you quickly pick or pluck a note in quick succession. The number of lines on the stem will indicate how many times you should pick or pluck in terms of time like tails on the quavers. The one in the example indicates a 16th. So as fast as you would pick a 16th note is how fast you pick the string in quick succession. The more lines, the faster you would pick or pluck the note for its duration.

This technique is unmistakeable if you hear it. Fair warning, it takes some practice to get this right and do it without it sounding like a sloppy mess. So practice slowly and in time using a metronome.

Check it out here:

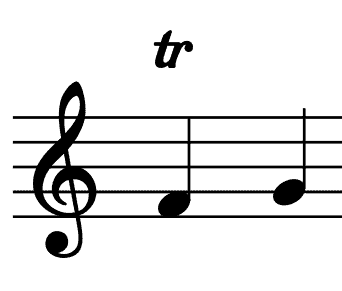

Trills

This sign will usually be written above a note. This indicates that you quickly need to alternate between that note and the note above it. The note it needs to alternate with will be written as the next note. If notes are directly on top of each other it means to play them at the same time.

Sometimes you may see a squiggly line to indicate how long the trill needs to go on.

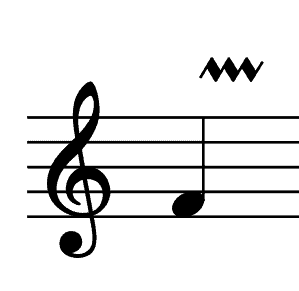

Vibrato

Vibrato is a pretty common technique used in guitar solos as well as when playing classical pieces. It can be done via your hands as in the video, or you can use a whammy bar if your electric guitar has one or even a vibrato pedal if your guitar is a semi-acoustic or electric.

The squiggly line at the top will usually indicate the duration. The longer the duration, the longer the squiggly line.

Accidentals

This is the collective names for sharps (♯), naturals (♮), and flats (♭) used outside the key.

- Sharps: Sharps make a note go up half a step (semitone).

- Naturals: If you have sharp or flat notes because of the key, a natural sign cancels that for that particular note and the subsequent notes that are the same in just that bar.

- Flats: Flats take a note down a semitone.

Conclusion

Learning to read sheet music and play it on the guitar can be a daunting experience, but so rewarding. It’s always a good idea to level up your skills. You’ll be able to play with a wider range of musicians and play any music you want that you struggle to figure out by ear.

Just keep at it and enjoy the fact that doing this work practically as well as theoretically makes the journey easier and more fun.

Happy learning!

Cheanné Lombard lives in the home of one of the new Seven World Wonders, Cape Town, South Africa. She can’t go a day without listening to or making music.

Her love of music started when her grandparents gave her a guitar. It was a smaller version of the full-sized guitars fit for her little hands. Later came a keyboard and a few years after that, a beautiful dreadnought guitar and a violin too. While she is self-taught when it comes to the guitar, she had piano lessons as a child and is now taking violin lessons as an adult.

She has been playing guitar for over 15 years and enjoys a good jam session with her husband, also an avid guitarist. In fact, the way he played those jazzy, bluesy numbers that kindled the fire in her punk rock heart. Now she explores a variety of genres and plays in the church worship group too and with whoever else is up for a jam session.