Of every type of scale you can play on the guitar, one that has really stuck with me is the pentatonic scale. Songs like Amazing Grace, Cotton Eyed Joe, and the iconic Led Zeppelin hit Stairway to Heaven all use it. The pentatonic scale has a very unique, and pleasant sound – but even better, it’s fairly easy for anyone to play! As you read on we’ll go over how the minor pentatonic scale works, and how you can get started in playing it.

Contents

What is the Pentatonic Scale?

The pentatonic scale is a scale containing only five notes per octave. Exploring its origins, the word “pentatonic” derives from the Greek word “pente”, meaning five, and “tonic”, which means tone. This is why the pentatonic scale, may sometimes be referred to as the five-tone scale.

This differs from the seven-tone scales we are used to, otherwise known as “heptatonic scales”. These heptatonic scales, house our “diatonic scales”, “diatonic” which is Greek for “through tones”. In a nutshell, these diatonic scales can be any heptatonic scale, provided it has five tones and 2 semitones within the scale, like our major and minor scales. (C Major, E minor, G minor scales… etc.)

Major VS Minor

Major and minor keys have always been two sides of the same coin, as they bring about very contrasting moods in one another. When it comes to pentatonic scales, this can give you some really cool melodic content, so it can be helpful to understand how these scales are constructed.

We’ll begin with our major pentatonic scales, which can be constructed in one of two ways. The first way is by taking five notes in consecutive order from the circle of fifths. For instance, the C major pentatonic scale, starting on note C within the circle of fifths going clockwise by five notes will give you: C, G, D, A, and E. Taking these notes and placing them in a scaled fashion, you now get the notes: C, D, E, G, and A in that order. This is our C major pentatonic scale.

The second way, however, is by taking its diatonic scaled version and removing its fourth and seventh scale degrees. For instance, let’s look at our C major scale’s diatonic form:

C > D > E > F > G > A > B > C

The underlined notes inside the scale are to indicate our fourth and seventh scale degrees. If we were to remove them both, we would be left with: C > D > E > G > A > C. Whatever way you choose to make your major pentatonic scale, the result is the same.

Our minor pentatonic scale, however, is a little different than its major counterpart and can be constructed by taking away the second and sixth degrees of its diatonic form. If we went to C major’s relative key, A minor, then its diatonic scale would look like this:

A > B > C > D > E > F > G > A

The second and sixth degrees of our A minor scale have been underlined, therefore, removing them would give us: A > C > D > E > G > A. This is our A minor pentatonic scale.

How to Play the Minor Pentatonic Scale

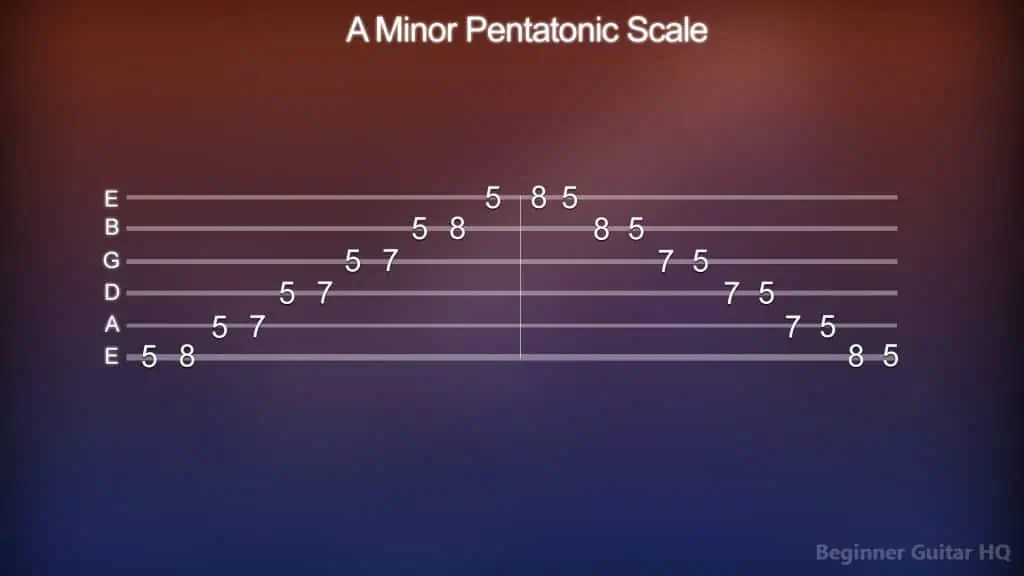

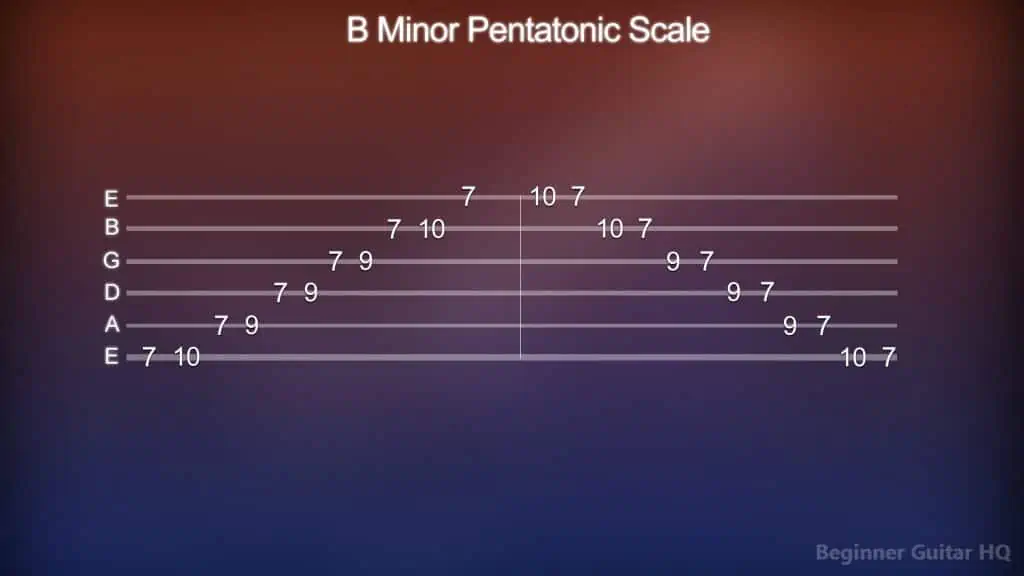

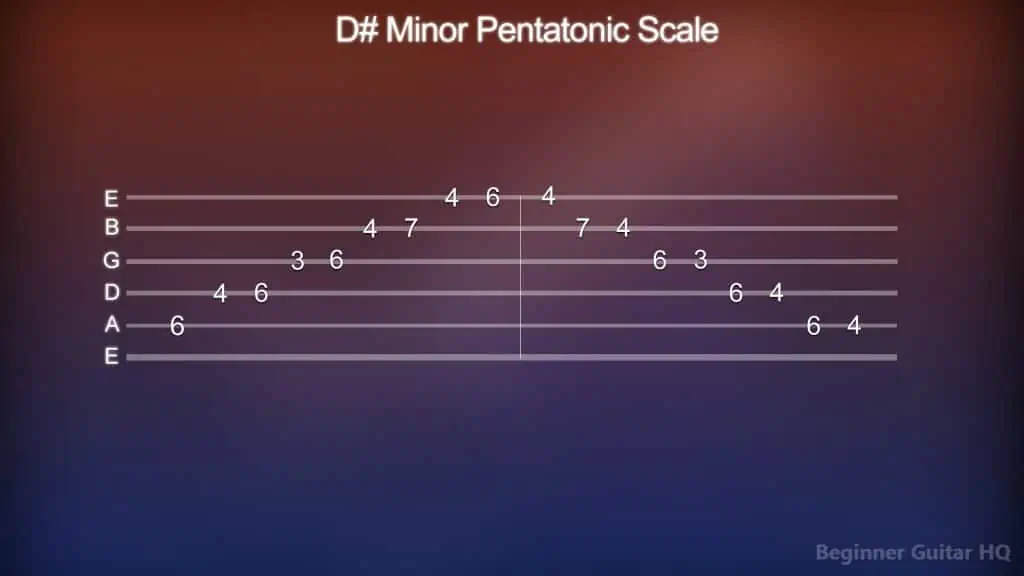

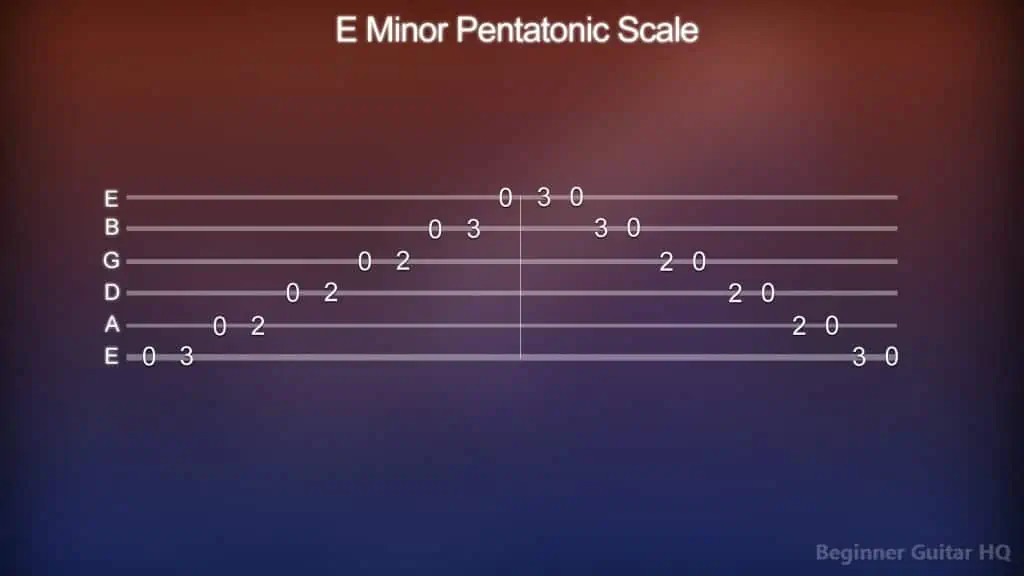

Now that we have covered how these scales are built, let’s go over how they are played. We have our A, B, C#, D#, E, F#, and G# minor pentatonic scales and we’ll cover each one in order:

Tablature diagram of the “a minor pentatonic scale” played from the fifth fret.

Tablature diagram of the “b minor pentatonic scale” played from the seventh fret.

Tablature diagram of the “c# minor pentatonic scale” played from the fourth fret.

Tablature diagram of the “d# minor pentatonic scale” played from the sixth fret.

Tablature diagram of the “e minor pentatonic scale” played from open note position.

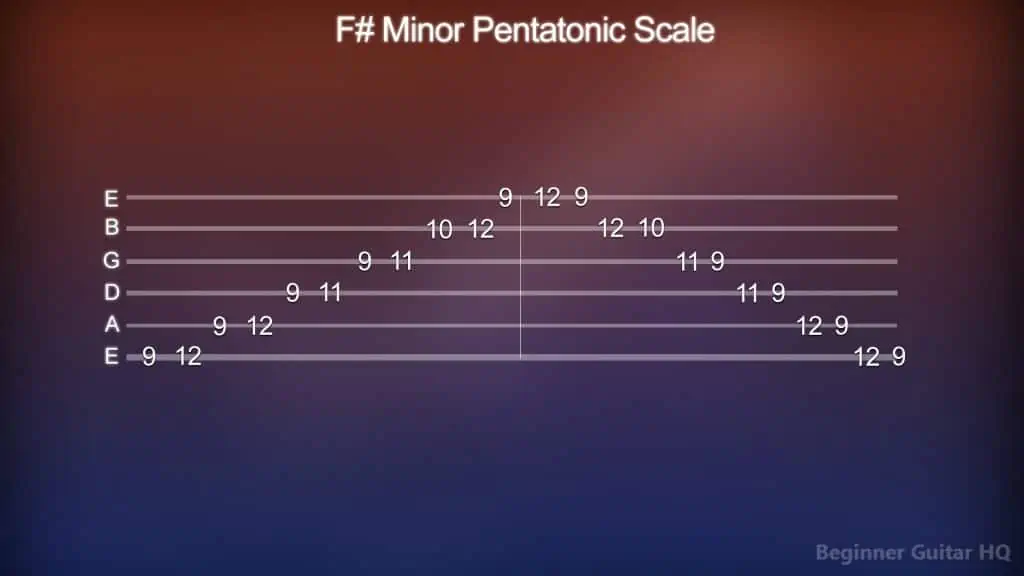

Tablature diagram of the “f# minor pentatonic scale” played from the ninth fret.

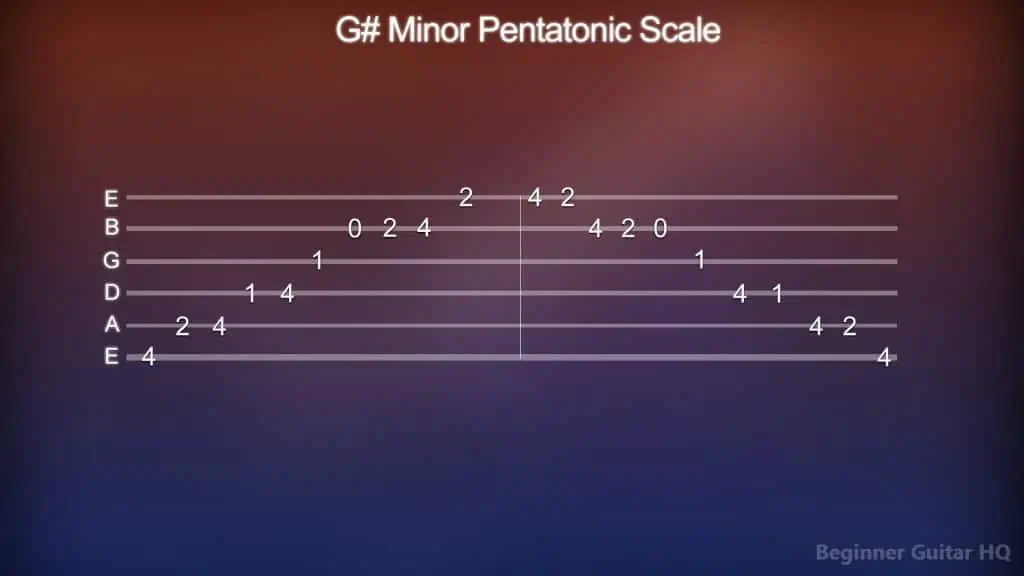

Tablature diagram of the “g# minor pentatonic scale” played from the fourth fret.

Trouble With Tablature?

If you are relatively new to guitar and don’t understand how to read tab, fret not, it’s very simple. Each of the horizontal lines represent a string on the guitar, with its corresponding name on the left. The E on the bottom is our low E string, and also the lowest note you can play in standard tuning. On the other end, we have our high E string and our A, D, G, B strings in between.

The numbers you see on each string represent the frets to be played. If you’ve got a (3), that’s the third fret and should be played on the corresponding string, the same would occur for (1), (7) and really any other number you would encounter. When you see a “0”, that indicates that you are to play an open note. An open note is when you play the string, but don’t fret a note on it.

And there you have it!

How to Practice With Scales

Practicing with scales can be one of the best ways to build up your finger strength and dexterity. Amongst all of the different types of scales, you will get various finger patterns and different melodic content which can make practice more exciting. We have gone through about half of the circle of fifths played on the pentatonic scale, so how can we make the most of them in practice?

Well, it can be helpful to have a metronome first and foremost before practicing any scales. A metronome will help you keep on time and adjust the tempo comfortably to your playing ability. This also allows you to set yourself goals in achieving clean runs of a scale at a different BPM (beats per minute). A recommended practice, especially for beginners is to start with something relatively slow, like 40 – 60 BPM. This might be fairly painful, especially if you love to zip through scales, but if you can’t play it clean at a faster pace you need to slow it down. As you improve you may want to increase it by 3 – 6 BPM each time, however, the choice is yours.

Exercise 1

When you’re playing through scales, the most standard practice you may try is to simply play the scale upward 2 octaves and then back down. Except, when you’re about to hit the root note to finish the scale, you simply hit the fret next to it (a fret higher) and go back up using that as your new root note. Following that, you come back down and rinse and repeat. You can do this all the way until you hit the 12th fret of the guitar without messing up. You can define the levels of what you call a “mess up” depending on your skill level. This can be defined as an accidentally muted string, a buzzing string, or a wrong note. Personally, however, if you are a new guitar player, I would correct the note played, and continue on until you can get used to this.

Exercise 2

An additional exercise you can pile on to the prior method is what I think of as a pendulum scale exercise. If you think of a pendulum clock swinging back and forth, that’s what we will be doing with the scale.

Using this method of practice, we would start on our 1st degree of the scale, and then proceed to play the 2nd degree after. Unlike the prior method, we wouldn’t then move to our 3rd degree, but instead, we would return to our 1st degree. Then we would play our 2nd degree, and then our 3rd degree, but then return to our 2nd degree and back to our 1st degree. So you kind of get the idea, it goes forward, then all the way back to the start, then a little further, and then returns to the beginning, and so on.

Once you reach the peak of the scale, you would do the exact same thing as the prior method in landing on the fret next to the 1st degree and using that as your new root note. Continue that until you reach the 12th fret without messing up.

Exercise 3

The third method is playing in thirds. If you are familiar with how intervals work, you’ll typically be skipping a note in the scale and playing the one after. Once you play this note, you’ll then take a step back by a second, and then play an interval of a third higher from there. So on a C major scale, the notes would look something like this:

C > E > D > F > E > G > F > A > G > B > A > C

Once you’ve gone through the two octaves, you’d return back down and land on the fret next to our tonic and use that as the new root note.

Exercise 4

Now that you’ve gotten the hang of it, it’s time to put it to use. If you can find a song you enjoy, or a nice backing track that falls in the same key as that scale, practice improvising with it. The idea of improvising is to only play notes that fall within the key, and do your absolute best not to mess up or play a wrong note. As you get more comfortable with it, try challenging yourself and playing from different spots on the neck but within the same key. This can ultimately help familiarize yourself with the notes on the fretboard and make you more confident in improvisation and soloing.

Spider Exercises

If you are having trouble playing clean, maintaining posture, or coming down directly on the strings and the prior exercises aren’t cutting it for you in terms of technique, spider exercises can help with this. You can start this type of exercise by playing from the first fret and moving chromatically with all four of your fingers up each string.

Starting from the low E string, you would play the frets: 1 – 2 – 3 – 4, but while doing so, keep your finger glued to that string. Then when you have to move to the A string, only one finger changes to the string at a time. So your index will change to the first fret of the A string while the rest of your fingers stay on the low E string. Then after, the middle finger follows on the second fret of the A string, the ring finger to the third fret, and the pinky to the fourth fret of the A string, each of them one at a time, and so on up each string.

As with the exercises before this, you’re going to come back down in reverse playing the frets 4 – 3 – 2 – 1. This might be a little tricky and awkward at first, because the sound of each note as you’re changing strings might be a little “clunky” and disconnected. As your fingers get used to these changes it will smooth out, so it’s important you get used to the motions.

You may also choose to play no notes at all, but to simply get used to the act of moving your fingers in this way, which is a great way to start spider exercises until you can add your picking hand into the mix. The important thing to look out for when doing these exercises is that your fingers are coming right down on the string, and not coming into contact with the string beneath it. It may be difficult at first, but you will thank yourself in the future as this will help in cleaning up your guitar playing technique.

What Chords Work Within a Pentatonic Melody

When trying to make chords to go along with a pentatonic melody, it’s not actually as complicated as you would think! This is in part due to the notes of a pentatonic scale deriving from those of a natural major and minor scale, but with certain notes taken out and not added.

However, learning to play chords that go well together involves a lot of knowing the key, scale degrees, and the composition of its different triads.

Keys

The key of your scale is the fundamental starting point for the steps to come. To find the key, you’ll likely have to consult the circle of fifths. The circle of fifths is a handy diagram that displays the sharps and flats used within the most common major and minor keys. It’s fairly straight foreward, however, if you are struggling to understand which notes are exactly sharp, and which notes are flat there are a couple of helpful acronyms to help you:

For sharps: Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle

For flats: Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’, Father

The idea behind these acronyms is that each word starts with a letter representing a note that is to be sharp or flat. As you go further, either clockwise or counter-clockwise, an additional sharp or flat is added. For instance, in the key of C major/A minor:

Clockwise

C Major (a minor): no sharps

G Major (e minor): F#

D Major (b minor): F#, C#

A Major (f# minor): F#, C#, G#

E Major (c# minor): F#, C#, G#, D#

B Major (g# minor): F#, C#, G#, D#, A#,

F# Major (d# minor): F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#

C# Major (a# minor): F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, B#

Counter-Clockwise

C Major (a minor): no flats

F Major (d minor): Bb

Bb Major (g minor): Bb, Eb

Eb Major (c minor): Bb, Eb, Ab

Ab Major (f minor): Bb, Eb, Ab, Db

Db Major (bb minor): Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb

Gb Major (eb major): Bb. Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb

Cb Major (ab minor): Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, Fb

Scales

Now that we have our key signature, we can now build our scale. For this example, we will use the natural A Major (f# minor) scale:

Major: A > B > C# > D > E > F# > G# > A

Minor: f# > g# > a > b > c# > d > e > f#

Each of these notes has a corresponding degree with a given name:

A Major (f# minor) = 1st degree (tonic)

B Major (g# minor) = 2nd degree (supertonic)

C# Major (a minor) = 3rd degree (mediant)

D Major (b minor) = 4th degree (subdominant)

E Major (c# minor) = 5th degree (dominant)

F# Major (d minor) = 6th degree (submediant)

G# Major (e minor) = 7th degree (leading tone)

A Major (f# minor) = 1st degree (tonic/octave higher)

Triads

With each note on these scales, you can form a trio of notes known as a triad (a type of chord). Major triads are formed using the major 3rd (M3) interval from the tonic to the mediant, and a minor 3rd (m3) from the mediant to the dominant. Minor triads, however, are done the opposite way; a minor 3rd between the tonic and mediant, and a major 3rd between the mediant and dominant.

A Major Triads:

A Major – A, C#, E

b minor – B, D, F#

c# minor – C#, E, G#

D Major – D, F#, A

E Major – E, G#, B

f# minor – F#, A, C#

G# diminished – G#, B, D

f# minor Triads:

f minor – F, Ab, C

g diminished – G, Bb, Db

Ab Major – Ab, C, Eb

bb minor – Bb, Db, F

c minor – C, Eb, G

Db Major – Db, F, Ab

Eb Major – Eb, G, Bb

The triads listed above can help us build ourselves chord progressions that flow nicely together. Using these, we can now apply them to our pentatonic scale.

Major Pentatonic Scale

As we know within a major pentatonic scale, it’s essentially a natural major scale, except for having the 4th degree (subdominant) and the 7th degree (leading tone) taken out. These are the degrees that typically build the most tension within a chord progression, and also what give the major pentatonic scale its peaceful and beautiful sound. The general idea, however, is that the major pentatonic scale could be played along with the compatible chords used in the diatonic scale. For instance, we have our compatible chords within the A major scale:

- A Major (tonic – 1st degree)

- b minor (supertonic – 2nd degree)

- c# minor (mediant – 3rd degree)

- E Major (dominant – 5th degree)

- f# minor (submediant – 6th degree)

And when we take the A major pentatonic scale, we get the notes: A, B, C#, E, and F#. Which can fit in perfectly with the chords to make some really cool sounding solos.

Minor Pentatonic Scale

The minor pentatonic, on the otherhand, replicates the natural minor scale, except for the 2nd degree (supertonic) and the 6th degree (submediant) being taken out. If you were to play a minor pentatonic melody in the key of f minor, using the f natural minor scale, we can find the chords that go well with it:

- f minor (tonic – 1st degree)

- Ab Major (mediant – 3rd degree)

- bb minor (subdominant – 4th degree)

- c minor (dominant – 5th degree)

- Eb Major (leading tone – 7th degree)

Taking the remaining notes within the f natural minor scale, we get F, Ab, Bb, C, and Eb, and we have our playable chords within our F minor pentatonic scale.

Conclusion

Now you know how to play the minor pentatonic scale, as well as what’s needed to play along with it. Pentatonic scales in their entirety are very fun and simplistic, as realistically, it’s just a major/minor scale with reduced notes. You may even choose to take things up a notch and learn one of its variations such as the diminished or augmented pentatonic scale, or even the “Japanese scale” which is based on the Phrygian mode. Nevertheless, it’s a very nice scale to incorporate into your daily practice to improve your fingerwork. Taking what you now know, how will you make use of the pentatonic scale? More importantly, how may using the pentatonic scale splash into other areas of your practice or songwriting?