A lot of chords you’ll hear and play are diatonic, meaning they’re mostly going to sound ‘good’. However, eventually you’re going to want to add a bit of interest to what you’re playing by adding some non-diatonic notes into interesting places.

In this important guide, I’ll talk you through the process of adding dissonance to your guitar chords.

If you’re looking for a place to start learning chromatic melodies, then look no further…

Contents

Diatonicism V Chromaticism

Most of our guides here at BeginnerGuitarHQ are based on diatonicism. Whether you’re trying to pick up a grasp of how to play standard triadic chords or learning some beginner melodies to play on guitar, they’ll typically be diatonic to one key. Check out these major chord variations if that is what you’re looking for.

This essentially means that within a scale, you’ll make your chord or melody up using notes that exclusively exist within this scale. For example, a C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) could create melodies or chords using only notes from this scale and they will be diatonic no matter how they sound. A C major triad, for example, is just as diatonic to the key of C major as a B diminished chord is, because both are made up exclusively of notes from the C major scale.

If you want to get really technical, to be diatonic is to be found within a scale that uses 5 whole steps and 2 half steps with the 2 half steps separated from each other by either 2 or 3 whole steps. This means various modes and the natural minor scale also fall into this category.

In terms of playing chromatic melodies, this is simple. Any note used that lives outside of the scale you’re using is a chromatic note. When playing dissonant (an ‘irregular’ sounding) chords, they might not be chromatic. This makes things a little confusing.

A chord such as the B diminished mentioned above is both diatonic and dissonant due to it being made up of notes from the same scale, but including the dissonant tritone interval. A B minor chord used in the key of C would not be dissonant, but would be chromatic as it borrows an F# from another key.

Below, I’ll talk you through dissonant chords that happen to be diatonic to keys. This is relatively simple to get used to. Then I’ll move onto the use of chromatic chords; these may or may not be dissonant, but will always borrow chromatic notes from non-diatonic keys.

If you’d like to check out a similar guide, but with a focus on chromatic melodic content, then click here.

Diatonic Dissonance In Guitar Chords

We often associate dissonance to chromaticism, but this doesn’t always need to be the case. You can remain completely in your home key and create some seriously dissonant chords.

In a C major scale, for example, there are 3 types of dissonant intervals available. The major 2nd connects C and D, D and E, F and G, G and A, A and B, so playing any of these notes together will create diatonic dissonance.

Similarly, the even more dissonant minor 2nd exists between E and F as well as C and B. The once illegal tritone (augmented 4th/diminished 5th) is found between F and B. This means you have the option of some extremely dissonant clashes within a diatonic scale.

Think about it: if you pressed down every white note on a piano, it would sound pretty dissonant, but technically it would still all be diatonic to C major. Now just play an E, F, C and B all at once. This gives you a tritone and two minor 2nd clashes in one chord, but it’s still diatonic.

In the example below, I’ll talk you through some diatonic chords which are still full of dissonance.

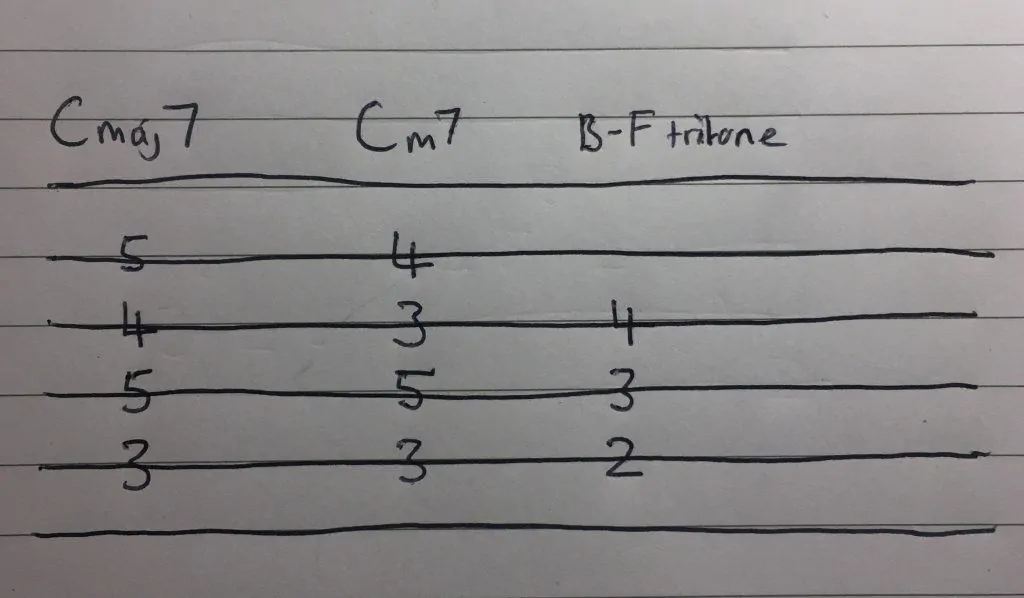

- Major 7 Chords: In a standard major scale you’ll be able to make two maj7 chords, on chord I and chord IV. For example, in C major the notes C, E, G and B are diatonic to their key, but still have a major 7th interval (which is the equivalent of a minor 2nd but reversed) and is highly dissonant. In the context of the chord, the sound is noticeably pleasant, but still adds a bit of interest to your harmonic writing. This means if you’re just starting out with your use of dissonant chords then this is a pretty safe choice.

- Minor 7 Chords: Similar to a major 7th chord, you can find minor 7th chords naturally and diatonically in the major scale. In C, the 7th chords on D, E and A are minor 7ths by default. This chord is arguably less dissonant, as the interval is a minor 7th (the reverse of a major 2nd) but it still creates a nice sounding chord with the addition of a spicing up your harmony.

- Major 9/11/13 Chords: This chord takes a standard maj7 chord and adds 9th, 11th or 13th intervals above. Typically, a Cmaj13 chord would imply the maj7 by default, but the 9th and 11th would not be present, just the 13th. The notes here would be C, E, G, B, A which means you now have an A clashing against the G and B either side of it, as well as the C and B clash from the major 7th interval.

- Minor 9/11/13 Chords: This chord abides by the same rules as the above. If you chuck a 13th on top of a Cm7 chord then the 7th will be implied, but not the 9th or 11th, meaning the notes are C, Eb, G, Bb, Ab. This again adds a new dissonance, though this time it is arguably stronger, as the Ab against G is a minor 2nd.

- Tritones: Technically a tritone isn’t a type of chord in itself, simply the interval which perfectly intersects an octave. When played together, the result is a highly dissonant sound which used to be referred to as ‘the devil’s interval’. In a major scale, the 7th and 4th degree clash in this manner, which means you have access to a very strong dissonance even when remaining completely diatonic to a major key.

Something to note about these chords is that they often exist in scales as diatonic chords naturally. However, they aren’t necessarily always a diatonic chord. For example, if you used a Dmaj7 in the key of C major, it would no longer be a diatonic chord, because the F# and C# aren’t in the key of C major.

Diatonic dissonance is relatively common in music. We’re able to hear chords such as the maj7 in various pop tracks, because while it has certain dissonances within it, the overall effect remains pleasant. Having said that, things like the maj7 chord are unlikely to be found in a particularly heavy piece of heavy metal, as it simply sounds too ‘nice’.

A Few Examples Of Diatonic Dissonance In Music:

- Arctic Monkeys- When The Sun Goes Down. The 3rd chord you hear in this track from Arctic Monkey’s first album is an Emaj7. Notice how this chord is pleasant sounding, but still brings an interesting twist to the harmonic language of the track. That’s the nice, diatonic dissonance at work. Check it out here.

- Chic- Le Freak. Blink and you’ll miss it but in the guitar solo of Chic’s ‘Le Freak’ there is a sneaky Am7 chucked in, showing how easy it is to put a bit of dissonance into a really poppy and accessible tune. Check it out here.

- Thelonious Monk- Monk’s Mood. One of Monk’s best tracks is full of diatonic dissonances. From the beginning, you can hear the contrast between those which are calming and diatonic such as the Cmaj9, and those which grate slightly more. Check it out here.

Chromatic Dissonance In Guitar Chords

Moving from diatonic dissonance, chromatic dissonance can also add a flair to your chords. Typically, this type of dissonance will be more jarring and unexpected, arguably creating a ‘stronger’ dissonance. This is because not only is the interval used dissonant, but the notes used are unexpected in their new context.

As explained above, you can find dissonance in C major. However, if you allow yourself not only every note from C major, but also every other note, you can create a whole new world of dissonance.

This gives you access to every single major 2nd, every single minor 2nd and every tritone to be combined in any way you want. Pressing down an entire octave of 12 chromatic notes will create one of the most dissonant noises imaginable, while carefully choosing which chromatic notes to add to your harmony can give it an interesting flair.

Below, I’ll talk you through some types of dissonant chords that are (almost) always chromatic.

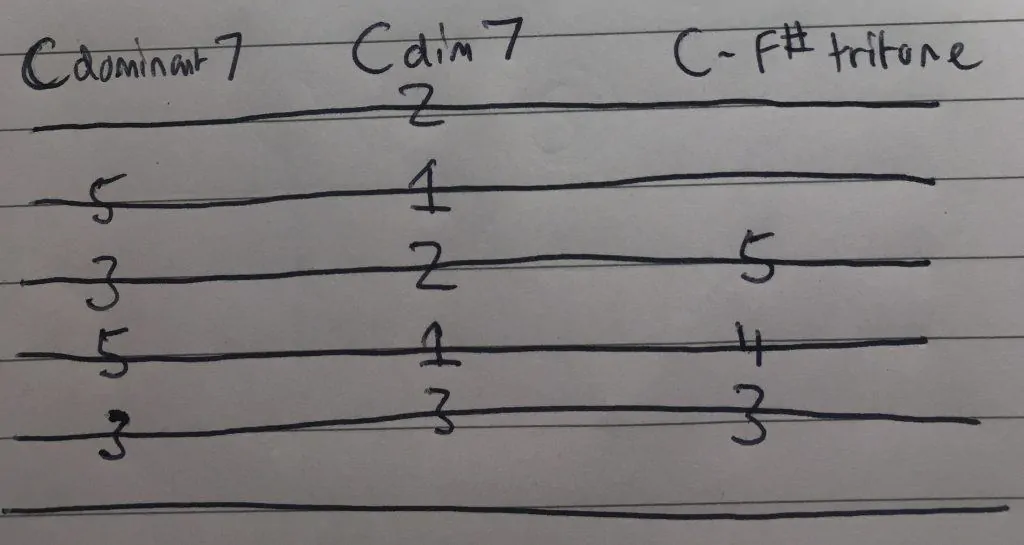

- Dominant 7 Chords: While a standard major scale can actually provide you with a non-chromatic dominant 7 chord (try adding a 7th to chord V- in C major the chord V is G, add a 7th and you have a non-chromatic G7 chord which is still dissonant), they are more often chromatic. For example, making your tonic chord into a dominant 7th requires a flattened 7th which doesn’t appear in a major scale. C7 forces you to bring a chromatic Bb into the major scale, or to sharpen the expected Eb when in a minor scale.

- Dominant 9/11/13 Chords: This concept follows on closely from a dominant 7th chord, but with added extensions as we make the chord more and more dissonant. If we take the C major example again, the flattened 7th is chromatic, then we add a D to create the 9th, an F to create the 11th and an A to create the 13th. In a dominant 9th, 11th or 13th chord, the assumption is that the 7th is always present, but not necessarily the 9th, 11th or 13th as well.

- Diminished 7 Chords: This is one of the most dissonant chromatic chords frequently available. It is made up of 4 stacked minor 3rd intervals, which in themselves aren’t dissonant, but from being stacked create two tritones. This means you have 2 different appearances of the most dissonant interval available within the same chord. This can be used to replace chord V in a particularly powerful cadence and will help resolve a chord sequence with a lot of finality. This type of chord appears within a harmonic minor scale (technically) but because a harmonic minor scale isn’t diatonic, this still counts as a chromatic dissonance.

- Major/Minor Chords: A rare chord to find due to its strange and often quite unpleasant dissonance created by using a major and a minor 3rd at the same time. This is down to two factors: the major and minor 3rd collision creates a semitone, minor 2nd dissonance which is particularly harsh, while the merging of major and minor creates an ambiguous chord with no rooting in a specific key. You’re pretty unlikely to find it in pop songwriting, but when used to create tension it can be an effective device. For example, trying to reflect a bittersweet situation.

- Added #/b Chords: If you saw a chord spelled like this: C7#9 then this would translate as a C dominant 7th with an added 9th, which is sharpened further than you’d expect, meaning it is always chromatic. The notes in this scenario would be C, Eb, G, Bb and D#, creating huge dissonance. The same can be seen with added flats in a chord. Dmaj9b13 would be a Dmaj7 chord with a 9th added, and then a 13th which is made flat (and thus chromatic). Made up of the notes D, F#, A, D#, E and Bb, the chord is almost diatonic to D major, but due to the b13, the chord is chromatic by default.

Something to remind you of here is that while this list of chords are always chromatic chords because they include simultaneous notes which don’t appear in the same scales. However, as I mentioned above, the chords which are able to be diatonic can still be chromatic.

Chromatic dissonances are often avoided in chart pop music, as they move away from the pleasant sound most pop artists are going for. For example, you’re rarely going to find anything more than a dominant 7th in the work of Ed Sheeran. Chromatic dissonance is normally reserved for the extended chords of jazz, the grinding aggression of extreme metal and the technical complexity of progressive rock, amongst various other genres.

A Few Examples Of Chromatic Dissonance In Music:

- Jimi Hendrix- Purple Haze. You’ll probably be familiar with the distorted tritone intervals of the introduction, but the verses of this Hendrix tune are full of dissonance. The main chord he hangs onto is the E7#9, which due to the nature of its extension actually almost creates a major/minor clash, as the #9 is technically the same pitch as a b3rd. Check it out here.

- John Williams- ET Flying Theme. This is a weird one and pretty hard to replicate on guitar as its played by a full orchestra in the original, but towards the end of this theme, you may hear the bass instruments playing a minor 3rd against the major chord above. This eventually resolves but it works really well to create some tension before the resolution. Check it out here.

- PREP- Cheapest Flight. This track is full of dissonance, with slightly simpler Fm7 and C#maj7s making their way in throughout. But listen to the end of the chorus, where the band chuck in a C7b9 creating a massive dissonance which helps to conclude the cadence. Check it out here.

Here is a detailed look at all extended chords

Alternating Between Major And Minor Chords

This is an interesting one, as the use of major chord in place of what would be expected to be minor (and vice versa) is not technically a dissonance. However, the effect can often be dramatic and unexpected, employing a chromatic note to change the tone of chord.

In C major, we’d expect the G chord to be major with a B natural. However, changing this to a Bb would create an unexpected sound which doesn’t fit the key. However, this wouldn’t necessarily be dissonant and can be used to particularly interesting effect.

A particularly common example of major/minor alterations is making chord IV in a pattern minor instead of major (or vice versa). Try brining an Ab into your use of the C major scale and see what I mean. This isn’t technically dissonance when played on its own, but its unexpected nature creates some interesting harmonies to expand your own work.

A Few Examples Of Major/Minor Alterations In Music:

- Radiohead- Creep. This chord sequence is immediately recognisable and one of the most important parts is the transition directly from C major to C minor. This isn’t technically dissonant in the true sense of the word, but it still creates a jarring and noticeable effect that your chord sequences could certainly benefit from. Check it out here.

- Lionel Richie- Hello. This major minor alteration creates a specific situation at the of the track called a Tierce de Picardie. This is when a piece of music in a minor key suddenly ends with an unexpected major chord. Again, this isn’t technically a dissonance but its effect is still strange, yet in almost all situations (including a lot of classical piano music) its effect is very pleasant. Check it out here.

The Use Of Cluster Chords

We’ve looked at a lot of relatively simple dissonances that will fit into many styles, but there are types of dissonance which are rare and particularly grating to hear.

A cluster chord is theoretically a cluster of next door notes combined. This can exist in a diatonic setting, in which you hammer out a mesh of next door notes (at least 3) from one scale. This creates some serious dissonance, but can be increased further by being used chromatically.

Playing 3 or more next door chromatic notes can create an even further level of chromaticism. This would end up so jarring that it is rarely found in popular music, and is more likely to be found for dramatic effect in film score, for example.

A Few Examples Of Cluster Chords In Music:

- The Beatles- A Day In The Life. In the strange middle section which connects both halves of the song, you’ll hear this noisy section made up of clusters of notes. It gives a massive amount of dissonance and tension which builds up before the second half of the track kicks in. Check it out here.

- Scott Joplin- Wall Street Rag. In a slightly more normal use, the piano work of Scott Joplin often bounces around with cluster chords in the left hand. These typically take the form of three notes separated by just a tone, so aren’t overly dissonant and instead give a pleasant sound of a crunchy jazz chord. Check it out here.

An interesting thing to note is that without some questionable tuning methods, its essentially impossible to create a chromatic cluster chord on the guitar. Unless you have some seriously impressively long fingers, you’ll struggle to create a true cluster.

If you’re looking for jarring minor 2nd dissonance, try playing the 4th fret of any string at the same time as the open version of the one above it.

In Conclusion…

You have a lot of dissonance available to you and are able to control it in a variety of ways. You can stick to pleasant sounding diatonic dissonance and give your playing a little interest and flair. You can create chromatic chords which add even more of an edge, and can sound fantastic when employed in the right places. You can even bring intentionally harsh sounding, grating dissonances by combining some seriously angry intervals in your music.

Just make sure you test it all out first- dissonance can sound terrible if not used in the right place.

Dan is a music tutor and writer. He has played piano since he was 4, and guitar and drum kit since he was 11.

He plays a Guild acoustic and a Pacifica electric. He has been sent to many festivals and gigs (ranging from pop to extreme metal) as both a photographer and reviewer, with his proudest achievement so far being an interview he has with Steve Hackett (ex-Genesis guitarist).

He ranks among his favourite ever guitarists, alongside Guthrie Govan, Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, David Gilmour and Robert Fripp. His favourite genre of music is progressive rock, which he likes to use as a reference point in my teaching, thanks to its huge complexity in structure, rhythm and harmony. However, he is also into a lot of other genres including jazz, 90’s hip-hop, death metal and 20th century classical music.