At BeginnerGuitarHQ, we want to keep you at the top of your musical game in every way possible. Sure, we can teach you how to play the guitar really well, but you’re also going to need to gain a certain level of theoretical understanding to take your playing to the next level. As such, we’ve provided you with a checklist of the most important aspects of music theory, including miniature guides to the basics and links to more comprehensive guides to specifics.

In this important guide, I’ll help you get a basic understanding of the most important music theory starting points.

If want to be able to understand exactly what you’re doing with your guitar, then look no further than this guide.

What Is Music Theory?

In short, music theory is the study of the theory behind music. Sounds simple, right? Well, up to a certain point, it is. Labeling an ‘A’ as an ‘A’ is technically related to the theory behind music, as it assigns meaning to a sound. However, we can take this to much more complex or wide-ranging angles and bring music down to effectively a science.

The main areas in musical theory are structure, texture, harmony, tonality, melody, rhythm and timbre. However, many of these can be widened to include a variety of related concepts that make up a wider entity. Rhythm, for example, can be expanded to include tempo, metre and specific rhythmic values of a note.

As this is just a checklist, we’re going to cover every angle of music theory via a whistle-stop tour that should introduce you to concepts that you can look at in more detail elsewhere on the Beginner Guitar HQ website.

Structure

As you’re probably aware, structure is the way we view the overarching form of an entire piece of work. This means that certain sections in a piece will be given a distinctive name in order to keep a grasp on the returning sections and their purpose in the piece as a whole. We’ve separated classical and popular music into two distinct halves here, as the two often follow very different structures.

Popular Music

The most common form of structure in popular music is the verse-chorus organisation. In general, this means you’ll hear a verse in which lyrics change upon each repeat, and a chorus that remains the same.

Some other important terms to remember in popular music include: bridge (a section that provides contrast to the verses and choruses we have hear so far), intro (a short section at the start of the piece), outro (the concluding passage of a piece).

The most common structure in popular music is: intro, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, chorus, chorus, outro.

Classical Music

Classical music very rarely employs a verse-chorus structure, instead falling back on more traditional ways of organizing music. The first thing to note is that classical music is often much longer than popular music, and as such, is frequently set into ‘movements’ that break up connected, but not overtly similar sections of a longer piece. It is important to note that certain genres, such as progressive rock, often use movements in particularly long pieces.

Some other important ways of distinguishing classical structures include: Sonata form (a form which uses an exposition, development and recapitulation to introduce ideas, develop them in detail and the return to them), arch form (a form that makes the shape of a bridge by introducing sections one by one, before reaching a midpoint and then reprising them in reverse order) and fuge form (a type of contrapuntal structure that places a variety of melodies on top of each other).

It is also important to remember that many classical structures refer to sections as ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C; etc. rather than giving them specific names.

Pitch, Scales And Melody

Pitches, scales and melodies all overlap in music theory as they are all built on the construction of the melodic lines that you hum after hearing a song.

Pitch

Pitch is something that exists outside of music. Every sound has a pitch, and when applied to music, this pitch can be assigned to a note. For example, a 440Hz pitch is referred to as ‘concert A’; a pitch that orchestras use to tune their instruments.

While a pitch can theoretically be of an frequency, the physical range of human hearing moves from 20Hz to 20,000Hz and deteriorates with age. The lower the frequency, the slower the sound waves move and the lower the pitch we hear. The higher the frequency, the faster the sound waves move and the higher the pitch we hear.

Scales

A C Major Scale

A scale is a way of organising pitches. A smooth movement from 0Hz to 100,000Hz wouldn’t really be a scale, as it would encompass every minute pitch. Western music typically follows a set of pre-determined pitches that relate to the 440Hz mentioned above, but various other tuning systems exist around the world and would likely sound ‘out of tune’ to the Western ear.

The Western chromatic scale organises a specific set of pitches within the human hearing range, and allows us to move up through every single note. While we are used to this sound, it’s important to remember that this doesn’t nearly cover every single pitch.

Other scales include the major and minor scales, which are an even more refined scale than the chromatic and are the two most often used in Western music. Each scale begins on a specific note, but can be transposed to have the same qualities, but be local to a different note. For example, C Major is made up of the notes C, D, E, F, G A and B but you could transpose this to F# (F#, G#, A#, B, C#, D#, E#) and while almost none of the note overlap, the tonal quality would remain the same.

Modes

A mode is a type of scale or tonality built on something aside from the typical major and minor scales and keys we are used to. An easy way to explore the major modes is by viewing them as a selection of white notes that start on a different note to the C major scale we’d expect to create using white notes. As such, the Dorian scale is the white notes from D-D, creating a distinctive sound.

However, there thousands of modes that can be created using similar principals but starting on a different note and using different types of scales as their base. Using the notes of the F major scale but starting and ending on C, for example, would create a Mixolydian mode.

The D Dorian Mode

Melodies

We don’t need to spend much time on melodies as they are one of the most accessible and clear areas of music theory. A melody is effectively a selection of pitches organised into a horizontal line that creates a (hopefully) memorable tune.

The tone of a melody is based around the scale/mode it takes its notes from. Typically, the darker (more flats) a melody is, the more negative it’ll sound, while the brighter the scale used (more sharps) the more uplifting it should be.

Tonality And Harmony

The ideas of tonality and harmony often overlap as harmony is created from notes that exist within a tonality.

What Is A Key?

Using what we already know about scales, the concept of tonality is something rather easy to grasp. While a scale is a selection of notes organised into a specific order, a key is just those notes in their unorganised form. If you’re playing a C major scale, for example, you must play those notes in order. If you play them in whatever order you want, you’re simply playing in the key of C.

The Modes

The same applies for modes. If you’re playing a Mixolydian scale, you’re playing a set of Mixolydian notes in an order. If you play notes from a Mixolydian scale but create a melody of your own from them, then you’re using the mode in place of a key. Be careful not to refer to a mode as a key, though.

Transposition

The idea of transposition call also be brought back to the idea of scales. As mentioned above, the C major scale can have all of its intervals taken up to F# to create an F# scale which has almost no notes in common. Despite this, their tonal feel is the same.

Transposition between keys exists with the same principal in mind. If you had a song that was played in C major and you brought it up to E major, it would be in a different key, but the intervals and therefore the feel and sound of the song would remain the same, just at a higher pitch.

What Is A Chord?

A chord is a series of notes heard at the same time. A chord can be as simple as two notes heard together, or as complex as a cluster of a hundred notes all played at once.

Diatonic chords are chords that fit within the key they can be created from (a C major chord is made up of C, E and G, all notes that are part of C major). Non-diatonic chords are chords that don’t exist in the key they are being used in (F#m in C major is non-diatonic as F# and C# don’t appear in C major).

Simple Chords

Simple chords are often diatonic, consonant and made up of relatively few notes. That C major chord above is the perfect example: it isn’t jarring to hear, it fits its key and it has just three notes.

Simple chord sequences can be made up from the key they are a part of and will sound ‘correct’ to a listener. One of the most common sequences in popular music is the I-IV-iv-V sequence. In C major this is made up of the chords C, F, Am and G, which are all simple, diatonic and consonant.

Complex Chords

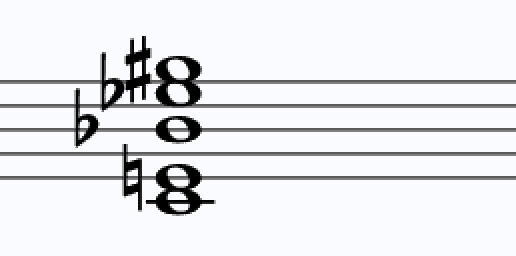

A Very Complex Chord

Complex chords are, as you may have guessed, a lot more complex. There are a lot more varieties of complex chords available. This could mean they have more than three notes, which would typically also create dissonance. A C7 chord, for example, is made up of a C major chord, but includes a Bb. This is: non-diatonic to C major, uses four notes and has a dissonance of a tritone between E and Bb and a minor seventh between Bb and C.

You could take things to an even higher degree of complexity and create a chord such as an Eb7#9b11 .This is an Eb major chord with a seventh above (Db), as well as a #9 (F#) and a b11 (Ab). This creates dissonance from every angle and includes many notes that aren’t diatonic to the same key. It’ll have a jarring sound which can be perfect in certain scenarios, and incredibly ‘wrong’ in others.

Complex chords can also be viewed as simple chords played out of context through modal borrowing. For example, a C major piece that suddenly introduces an Abmaj7 chord might sound beautiful, but as Ab and Eb are both alien to C major, there is a certain complexity involved, no matter how nice the chord sounds.

Texture

Texture is something many musicians rarely give much thought to, as it naturally occurs when a song is written. Many pop songs are built on a melody and accompaniment, but things like backing vocals and instrumental layers impact the texture of a song hugely.

What Is Texture?

Texture in music is effectively created through the different layers of instruments and what they’re all doing at any given time. This means a thick texture will typically include many instruments or fewer instruments playing more hectic, full lines. A thin texture will typically include less instruments or more sparse performances from more instruments.

Types Of Texture

Homophonic textures are the most common in music, built on a melody and an accompaniment. Polyphonic textures are rarer, as they include more than one separate melody occurring at the same time. Monophonic textures are the most simple, as they are built on a single, unaccompanied melody. Homorhythmic textures are built on multiple instruments each playing the same rhythm at the same time. Heterophonic textures are built on melody lines that are playing roughly the same melody at the same time, but with variation.

Rhythm, Metre And Tempo

Rhythm, metre and tempo all group together perfectly as they are the combined way of giving a sense of timing to music. The combination of metre and tempo will show you where to clap along, while a combination of tempo and rhythm will give a note its length, while a combination of metre and rhythm will create the feel of a melody or chord sequence.

Understanding Rhythm

Examples Of Rhythm In Action

Rhythm is the overarching term for the timing in music. Technically, tempo and metre are encompassed by rhythm, but rhythm also has its own distinctive action. For example, a semibreve rhythm implies that its note should be a held for four beats. A quaver, on the other hand, is held for half a beat. You should familiarise yourself with these terms as well as semiquaver, minim and crotchet, as they all give length to notes.

Different types of rhythm can also be created elsewhere. For example, if you see a dot to the side of a note, this means you play the type of note (minim, crotchet etc.) plus half of itself: a dotted crotchet would therefore last 1.5 beats. If you see a dot above the note, this means it should be played staccato. This tells you to bounce off of the note as soon as you play it, but to still count the length of the full note.

Things like triplets and quintuplets also come with a rhythmic implication. A set of quaver triplets, for example, would tell you to play three equally spaced notes within the rhythmic period that would normally be filled by two normal quavers.

The idea of syncopation is also important, as syncopated melodies will include notes that fall ‘off’ of the beat. Jazz is arguably the genre which places the most importance on syncopation in melodies.

Understanding Metre

Metre (made clear by a time signature) is the way of organising each bar of music into a certain grouping of beats. The most common time signature is 4/4. The 4/4 time signature tells a performer to play four crotchet beats in each bar and will be heard in the majority of popular songs. 3/4, also known as Waltz time, is similar but refers to using three crotches per bar instead.

The second (or bottom) number tells you which type of rhythm you should be counting in. A two would imply that you are using minims, while a four would suggest crotchets, an eight would suggest quavers, a sixteen would be semiquavers and so on. The top number tells you how many of these beats to use in each bar. 12/8, for example, means you’ll have 12 quaver beats in your bar, while 7/16 would be seven semiquavers.

Many time signatures are very simple and easy to get a hold of (4/4 for example) but some get very complex. A time signature of 17/16 is just one semiquaver longer than a bar of 4/4, thus making it seem very unnatural unless you’ve organised the inner beat groupings in a convincing and logical way.

Understanding Tempo

Tempo is basically the speed of a piece. A fast tempo will mean that a piece is played faster, while a slower tempo means a piece is played slower. Most studio recordings will have a set tempo that will persist throughout the piece, so the tempo on sheet music would give a specific BPM. In classical music, this is often rather different, and tempo is implied by a word with specific meaning. This gives a performer the ability to infer their own exact tempo based on the performance instruction.

Some of the most common include: Grave (very slow, between 30-40bpm), Adagio (slowly and expressively, between 65-75bpm), Moderato (moderate speed, between 100-110bpm), Allegro (fast and bright, around 135bpm) and Prestissimo (over 200bpm).

Timbre, Dynamics and Articulation

The remaining elements of music theory are slightly less interconnected, but still combine to effectively create the sound of the instrument(s).

Timbre

Timbre is quite literally the sound of an instrument. This word can be used to describe the specifics of a different instrument. For example, a violin has a much more fuzzy yet luscious sound than a piano, while a piano has the timbral capability to range from percussive to gentle.

Of course, various techniques and options exist to greatly change an instrument’s timbre. A piano, for example, could use its soft pedal to create a much softer, more muted timbre. A violin might use a Sul Ponticello performance instruction that tells the performer to play their violin closer to the bridge. Similarly, a pizzicato instruction tells the violinist to pluck a string rather than bow it.

These alterations can be taken even further via manual manipulation of an instrument. For example, a prepared piano has its timbre altered drastically by placing things like rubbers and nails in-between the strings.

Dynamics

Dynamics are one of the most simple concepts in music theory as they a have a very distinctive and definitive existence. They’re effectively based on volume.

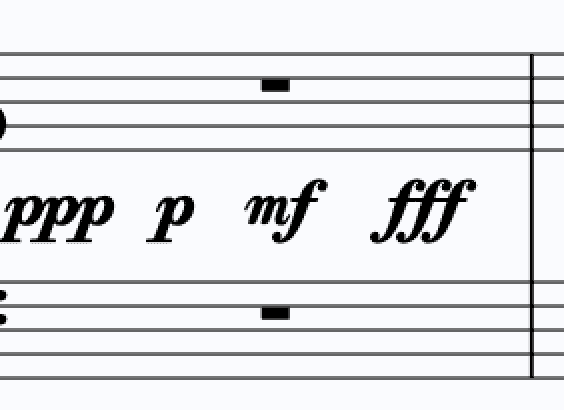

ppp (pianississimo) is an instruction to play incredibly quietly, while fff (fortississimo) is an instruction to play incredibly loud. Between these, come the likes of the most simple and common p (piano- quiet) and f (forte- loud). More middling volumes can be created via mf and mp, while sudden moments of loudness can be achieved through sfz instructions.

Some Different Dynamics

Articulation

Articulation is the way a performer brings passion and emotion into the specific way they’re playing a piece. In general, articulation isn’t something 100% necessary to make a piece sound recognisable to a listener (whereas a change of rhythm would change the melody dramatically), but it is incredibly important in making a performance interesting.

Things like staccato, accents and slurs help to tell performer when to emphasises a particular note or play a short passage particularly smoothly. Some moments of articulation help make the specific phrasing of melodies clear.

Reading Sheet Music

Of course, most of this theoretical knowledge is hard to make sense of or use when you don’t know how to read sheet music. You don’t need to be able to read sheet music in order to be a great musician, but it’ll really help you understand the theoretical aspects of what you’re playing or composing.

Tab

While the guitar tab isn’t the most common form of notation across music, it is arguably the most important for a guitarist to know. This is because it is a very simple system and applies well to guitar (especially popular music guitar) playing.

Simply view the six lines on the tab stave as each string on your guitar, and then each of the numbers you see as the fret you need to play. Read the tab horizontally and play through as you see each fret number. Some tabs will be open and allow for rhythmic interpretation (meaning you’ll often have to remember a rhythm in certain situations) but others will have rhythmic instructions as well. This will require some knowledge of standard notation…

Modern Music Notation

Standard Western notation is something most people will be familiar with. Unlike tab, it doesn’t apply to one specific instrument and can’t be viewed as a visual representation of an instrument. However, when you get a grasp of notation, you can take it to any instrument.

The key points are: the five lines. Notes will be placed either on or between these lines to tell you which pitch to play; the rhythmic instruction. This will be made clear by the type of note you see on/around the lines; the metre. This time signature will appear at the start of the stave; the key signature. This will be made clear with either #’s or b’s next to the metre; the clef. This is typically treble at the top and bass at the bottom, but other clefs exist; dynamics, articulation and a variety of performance instructions will be dotted around the score.

Other Styles Of Notation

While tab and notation are the most common types of sheet music found in the West today, they aren’t the only available. Some music is built around symbols, Solfège uses syllables in place of notes, while certain experimental musics use graphical scores instead. Around the world, especially in countries with different tuning systems, a variety of different types of musical score exist.