Triads are some of the simplest chords that you can play on your guitar. The shapes are generally pretty easy, and as long as you aren’t playing any open strings, the basic shapes can be moved all over the neck to play different guitar chords of the same quality. Knowing where to find them on your guitar is important, but knowing how to build them will help take your playing to the next level, as you’ll begin to understand how to build your own chords, and then use the notes in those chords to solo!

Contents

So, What’s a Guitar Triad?

Simply put, a triad is a 3 note chord. If you’ve ever played a C, G, D, or even Em chord, you’ve played a triad. Spoiler alert, those aren’t the only triads, but just some of the first we learn to play on the guitar.

You may be thinking to yourself that you’ve played these chords before, but you’ve played more than 3 notes. Well, yes, and no.

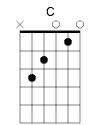

Though you may have strummed 4, 5, or even all 6 strings, you’ve really only played 3 notes. Take the C chord for example. The notes that you will play in this chord from low E to high E are: C – E – G – C – E. Notice how it’s only 3 notes?

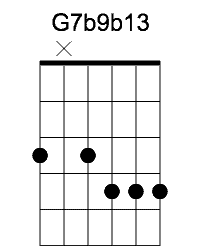

Once you begin to understand how chords are built, you will be able to see any chord, even a G7b9b13 and understand how to interpret it and how to play it. If you’re interested, I’ll tell you the notes of that chord at the bottom, and how to find them.

The Theory Behind Chords

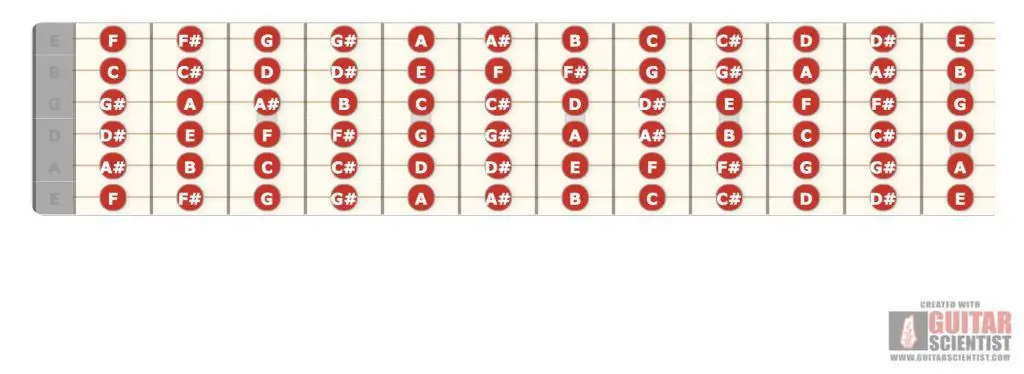

In order to understand how to build a triad, it is important to know a little bit of theory, and the best place to start is with the 12 notes found in Western music.

If you aren’t familiar with these 12 notes, here they are. A A#/Bb B C C#/Db D D#/Eb E F F#/Gb G G#/Ab and then it repeats back from A. Notice how there is no B#/Cb, or E#/Fb.

The notes that have a slash (/) between them are called enharmonic equivalents. This means they will be referred to by either note, though they sound the same to our ears.

So although A# and Bb are technically different notes, they are the same sounding note.

Tones, Semitones, and the Major Scale

As you move up or down one note at a time, you are moving a Semitone. If you skip a note, you are moving a Tone.

The guitar is such a wonderful instrument in so many ways. One of its great features is how visual it is and how easily notes can be found.

As long as you remember that each fret is a semitone away from the next fret, you will be able to find any note without too much thought. Once you can find the notes, you can start to build triads, and then even larger chords.

Chords are built from the notes found in scales, and if you’ve ever taken any music classes before, you’ve probably played a major scale.

The major scale is a simple pattern made up of tones and semitones, and goes as follows: Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone Semitone.

The major scale is simple to play on the guitar and can be played on one string by using the pattern above.

To keep it simple, we’ll start with the C Major scale because it has no sharps or flats in it.

If you write out all 12 notes starting from C and then put a circle around the notes in the scale by following the pattern of tones and semitones, you may find it helps.

C – C#/Db

D – D#/Eb

E & F – F#/Gb

G – G#/Ab

A – A#/Bb

B & C

Now that we have the notes of the major scale, we want to assign a number to each note in order to figure out how to build chords.

C = 1 (also called the Root)

D = 2

E = 3

F = 4

G = 5

A = 6

B = 7

C = 8, or 1

As you go into the next octave, D = 9, E = 10, F = 11, and so on. But chords will always be built using the odd numbers of 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13. This can get pretty complex and is best explored in another lesson, so I’ll leave it at that for now.

Building Triads

I mentioned earlier triads are simply 3 note chords, but what 3 notes?

The 3 notes are going to be the 1st, 3rd, and 5th degree of the scale.

From the Major scale, we can now build Major (1 3 5), minor (1 b3 5), and diminished chords (1 b3 b5).

As with the pattern of tones and semitones, there is a pattern of Major, minor, and diminished chords that goes like this: Major, minor, minor, Major, Major, minor, diminished.

In order to go one step further and build the chords, we will take every other note of the scale (1, 3, and 5) and stack them. What you will end up with will look something like this:

C E G = C Major

D F A = D minor

E G B = E minor

F A C = F Major

G B D = G Major

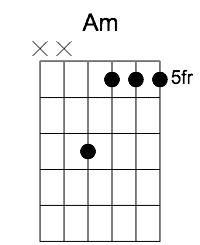

A C E = A minor

B D F = B diminished

The wonderful thing about this is that you can take these patterns and use them for any Major scale or chord.

As a more complex example, but to demonstrate the simplicity and repetitive nature of it, let’s build another major scale, but this time starting from Bb. In this example, you will find that we have a couple of flat notes but don’t let that frighten you.

To start, let’s write all 12 notes starting from Bb and circle the notes in the Bb Major scale.

Remember, this is found by using the pattern Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semitone. Because this scale is going to use flats and not sharps, I will leave out the enharmonic equivalents.

Bb – B

C – Db

D / Eb – E

F – Gb

G – Ab

A – Bb

Bb / C

Once you have found all of the notes in the scale, just stack them in groups of 3 using every other circled note..

In this case, we end up with:

Bb D F = Bb Major

C Eb G = C minor

D F A = D minor

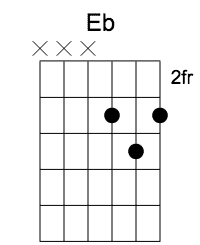

Eb G Bb = Eb Major

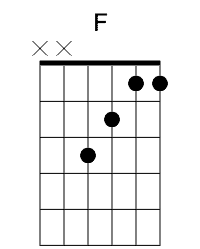

F A C = F Major

G Bb D = G minor

A Bb C = C diminished

Now that you’ve built some chords on paper, take a look at some of the chords you already know how to play and you’ll see that they’re just triads.

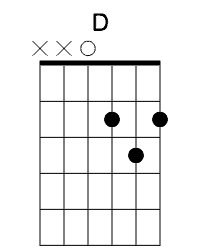

The C chord that you’ve played (found above), is just made up of the notes C E and G. The D chord is just D F# and A.

Build the major scale from D and stack those notes. You’ll see what I mean.

From low E to high E, you have an open D (the root) on the 4th string, an A (the 5th of the chord) on the 3rd string, another D (the root) on the second string, and the F# on the first string (the 3rd of the chord).

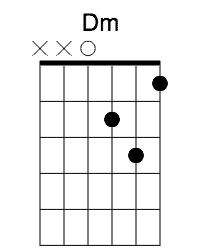

Now, what happens when you move the F# in that D chord down one semitone to an F? Play it on your guitar and you may recognize it as a Dm chord.

So the difference between any Major chord and any minor chord is that the third of the chord is either lowered a semitone from a Major chord to make it minor, or raised one semitone from a minor chord to make it Major.

Here is the formula for building our triads:

Major = 1 3 5

Minor = 1 b3 5

Diminished = 1 b3 b5

**Bonus**

Augmented = 1 3 #5

Moving Guitar Triads

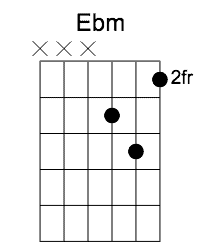

If you want to go even further with this, play the D or Dm chord on your guitar and move it up one fret, but only strum the strings that you have your fingers on (the top 3 strings), and mute the lower 3 strings (or just don’t play them at all). You are now playing either D# or Eb if you moved the D chord, or D#m or Ebm if you were playing the Dm chord. Move it up another fret and you’ll be playing E or Em, and so on.

Remember, you can move any chord anywhere on the neck, and as long as there are no open strings being played, the quality of the chord (Major, minor, diminished, Augmented) will not change, but the letter of the chord you are playing will change.

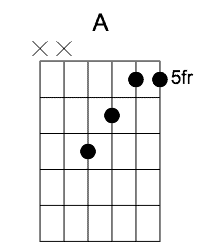

As one final example, take your standard F chord and move that shape up 4 frets. If you count semitones from the F on your 4th string, you will see you end up at A (F – F#/Gb – G – G#/Ab – A). You’re now playing an A chord.

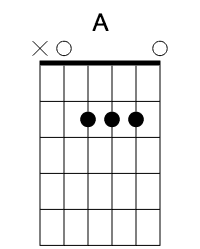

Don’t believe me? Play the open A chord the way you know how and you’ll hear the similarities. Here you are playing the notes A – E – A – C# – E

Go back to the new A, and if you look at the notes underneath your fingers, you’ll notice it is made up of A – C# – E – A. All the same notes, just in a different place and in a different order, or inversion. (If you aren’t sure about inversions, be sure to check back at a later date for an in depth review of them.)

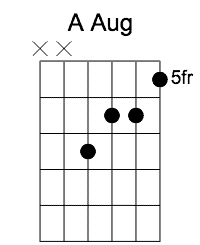

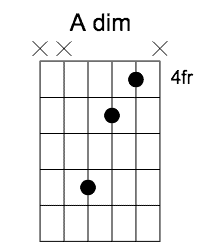

With your hand still on the new A chord, move the C# down one semitone to C, you’ll be playing an Am chord. Try and move the C# to C and the E down to an Eb and you’ve got an A diminished chord. Or leave the C# where it is and move the E up to E# (F), and you’ve got an A Augmented chord.

Final Thoughts

There is so much that you can do with a basic understanding of triads, and if you’ve made it this far and everything makes sense, congratulations!

If you’re still a bit unclear, just take your time with it. It won’t happen overnight, but the more time you practice playing and learning the notes on your guitar, the quicker everything will come together.

To end things for now, if you’re wondering about the G7b9b13 chord I mentioned earlier, you just need to write out the G Major scale and add in the additional notes. In this case, the 7 is also flat, so what you need is 1 – 3 – 5 – b7 – b9 – b13 (G – B – D – F – Ab – Eb). Just build the G Major scale and flatten the required notes.

In the diagram above, from Low E to high E, we have the notes G – F – B – Eb – Ab ( 1 – b7 – 3 – b13 – b9). I’ve left out the 5 because it doesn’t really add much to the chord.

Don’t worry if this isn’t clear, I’ll be sure to dive into building more exotic chords in the future.

Once you have a firm grasp of what notes are in each triad or chord, you can make really beautiful and melodic sounding guitar solos using the notes of the chords you are playing over. Stay tuned as that will be discussed in detail in an upcoming post.

Happy playing!