At BeginnerGuitarHQ, it’s our mission to teach you how to play the guitar as well as possible. One of the most important parts of a guitarists toolbox is the humble scale. You’ve probably become rather used to standard major and minor scales, but were you aware of the basically endless possibilities modes afford you? They can change the tone, style and feel of your playing with just one unexpected note.

In this important guide, I’ll be explaining how you can use the Dorian mode within your guitar playing.

If you’re on the lookout for a way to spice up your melodies, chords and improvisation look no further than this useful guide.

Contents

What Is A Mode?

The most important first thing to be aware of when approaching the Dorian mode, is what a mode actually is. Technically, the term ‘key’ only applies to diatonic music. As such, you can have your major and minor keys and be diatonic to them (that is, stay within them when playing), but you can’t really use the term diatonic to refer to a mode. A mode is, to all intents and purposes, however, basically the same as a key. You’d very rarely see the notes of the mode written out in a key signature, but they’re basically the same thing, just with more possibilities.

There Are A Lot Of Modes

Today, we’re looking at the Dorian mode (which we’ll get to in a moment) but there are hundreds more modes in existence. One way to look at modes is to imagine a piano. The white notes from C-C make a simple C major scale. Move up to D, and if you simply go from D-D without hitting a black note, you’ll be playing the Dorian mode. The same with E, F, G, A and B. Now remember that there is a minor scale equivalent (so the equivalent of having the same approach, but with the C minor scale as your basis), and a harmonic minor scale equivalent, and melodic minor, and all of the modes, and all of their variants. It basically goes on forever, but you don’t need to worry about that. For now, you just need to worry about the Dorian mode.

And What Is The Dorian Mode?

The Dorian mode is, in its purest form, the white notes from D-D. This means that a D Dorian scale is D, E, F, G, A, B, C. Obviously, this is the enharmonic equivalent of C major, so the notes are exactly the same; it’s the way you use the scale that changes things.

The most important notes in the D Dorian scale are:

- D. The tonic note is probably the most important note in any scale. It’s the root of your playing, and if you’ve successfully remained in the key you think you’re in, it should be the note which feels ‘final’.

- F. The F is another important part of giving the Dorian mode its trademark sound. This is the minor third above the tonic, giving the mode the key distinction of being a minor mode. If this was an F#, the mode would have a totally different character.

- B. The raised sixth is the note that makes this mode different to the natural minor scale. Where you’d normally have a flattened sixth here, this mode keeps things a little brighter by raising it by a semitone. This has a huge number of harmonic implications that we’ll look at below.

- C. The final note in the scale also has a major impact in keeping this scale separate from the harmonic minor. While a harmonic minor typically raises the seventh to create a leading note into the tonic, the Dorian doesn’t do this, relying on the Mixolydian-like seventh instead.

So remember: D, E, F, G, A, B, C

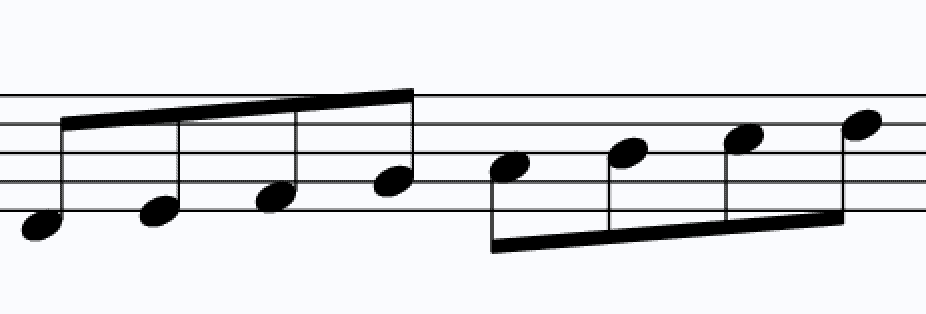

D Dorian Mode

Transposing The Dorian Mode

Moving The Dorian Mode To C

While looking at the Dorian mode in its most simple formulation gives us the simplicity of the D, E, F, G, A, B scale mentioned above, it isn’t as though the Dorian mode can’t be moved to every single other note.

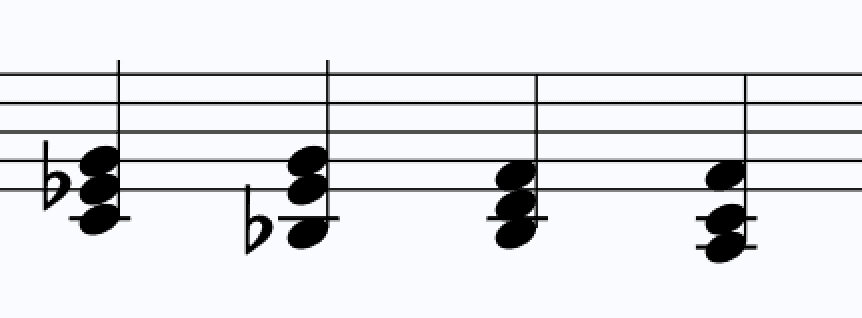

We can start with the C Dorian mode, which brings the D Dorian down by a major second. This means the C Dorian is made up of the notes C, D, Eb, F, G, A, Bb. We’ll now focus the rest of this guide around the C Dorian mode for simplicity, but remember that it can be moved to any note you need via transposition.

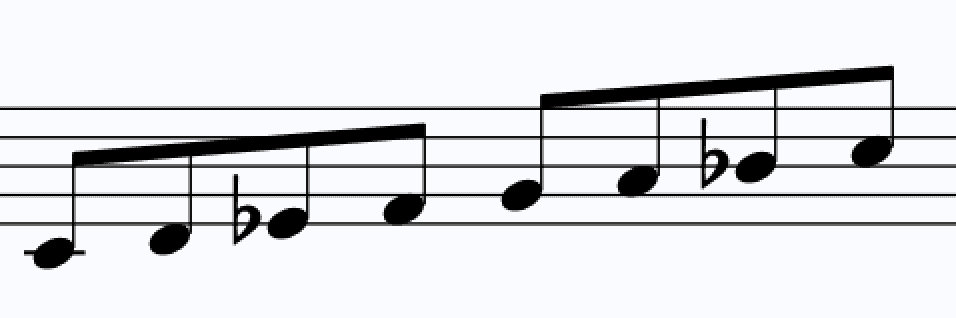

C Dorian Mode

Moving The Dorian Mode To Every Other Note

The easiest (but longest) way to do this is to simply look at the notes, and move every single one of them up by the amount necessary to reach the new tonic. For example, if you’re starting on C and want to play the Eb Dorian, then you need to move every note up by a minor 3rd. Take the D and move to an F, the Eb to a Gb, the F to an Ab. Keep going until you’re in the new correct place.

The second way, which is quicker but a little more complex, is the preferred method which will benefit your theoretical understanding of the mode as well as your use of it. You’ll need to remember the interval pattern of the Dorian mode:

Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone.

Now you can use this anywhere you want. To create the E Dorian scale, for example, start with that movement of one tone: E – F#. Then add a semitone to take you to G. Then move by four tones in a row: G, A, B, C#. The final semitone takes you to D, and then you’re one tone from being back on the tonic.

Apply this same logic to any note you may need to use, and you have a basic understanding of how to form the Dorian mode anywhere you want, and can start to use it in melodies.

Using The Dorian Mode In Melody

Avoid: Remaining Dorian For No Real Reason

One of the easiest traps to fall into when composing or playing any mode is the desire to stay firmly within that mode even when you don’t need to. There is no modal devil following you around, looking over your shoulder and forcing you stay in one place rigidly. If the change of chord you want to make doesn’t fit in the Dorian mode, then it doesn’t matter- make the move.

Similarly, if you’re trying to remain Dorian but the part of the piece you’re at sounds like it needs a key change, then do it. People change keys mid-song all the time, so moving away from the Dorian sound wouldn’t be an issue at all.

Do: Use It In Jazz Improvisation

One thing you may notice about the Dorian mode is that it sound lends itself very well to jazz. It appears often in the work of Herbie Hancock and Bill Evans, possible thanks to its smooth ability to raise that chord IV into a dominant seventh. This might make it seem like this is a mode only for pianists, but that certainly isn’t the case.

During a piece of improvisation on guitar, you’re likely to be playing rather fast and chromatically by default. On a minor run, sharpening the expected minor 6th is a great way to give a twist to your playing that isn’t going to potentially sound like a wrong note.

Do: Use Its Darkness To Your Advantage

As one of the minor modes, the Dorian has an innate darkness within it. This comes from two very important places. The minor 3rd that connects the tonic C to the Eb. This is the core part of a minor chord, so any movement between that is connected to negativity. Similarly, the G to Bb up at chord V is another distinct movement of a minor 3rd.

On top of that, the natural A (instead of the more expected Ab) means you can create an interesting clash between that and the Eb. Of course, in the standard minor mode you’d have the clash between Ab and D instead, but this allows you to take a slightly different approach.

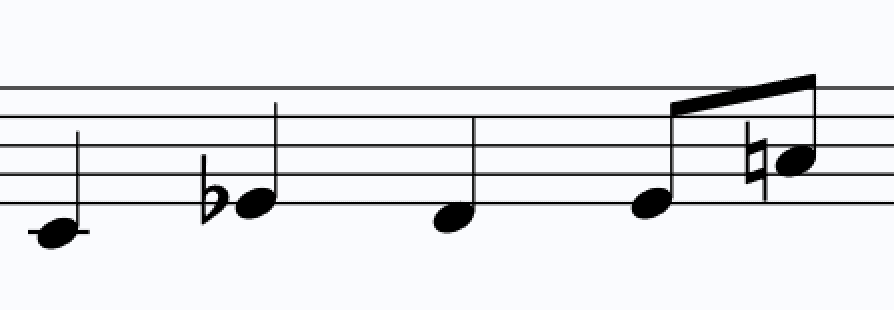

The Use Of Modal Darkness

Do: Also Make Use Of Its Slight Brightness

At the same time, the Dorian mode is also slightly brighter in tone than its standard minor cousin. Now, there is only one note different between the two modes, that is true. Despite this, their tone is incredibly different.

By raising that one singular note, the Dorian mode takes on a slightly more positive connotation. If you’re looking to get really specific, then you could perhaps employ a system that moves you from the minor (Aeolian) mode to the Dorian mode to imply a situation which is getting more and more positive as time passes.

Do: Emphasise The Natural 6th

That natural 6th is the core of the Dorian mode. Without it, you wouldn’t be in the Dorian. You could play every single other note around it, but without making sure that your listener knows that the A is natural, not flat, almost anything you were playing would imply the standard minor mode.

If you’re truly trying to create that distinctive Dorian sound, then you can’t really do it without the raised 6th. One way of doing this effectively is to run up to it from the Eb, to the F, to the G and then when the listening expects the Ab, continue on the run of tones and lean straight in the A. Not only does it make the note stand out, but it competes a whole-tone run which is embedded naturally in the scale.

Avoid: Accidentally Using The Natural 6th As A Leading Tone

An issue that raises its head in just about every mode at some point is that you don’t want to have accidentally used one of the unexpectedly raised notes as a leading note. In the Dorian mode, that potential comes directly from the raised 6th. Going down from a C to the A could, in many cases, accidentally make it seem like you are leading yourself towards a Bb tonic.

Similarly, the lack of leading note in this mode means that certain situations could arise where your tonic doesn’t quite feel like a tonic when you move to C from Bb. Having said that, keep in mind the fact that a temporary modulation isn’t a big deal- if it sounds better to move from the Dorian mode temporarily, then do it.

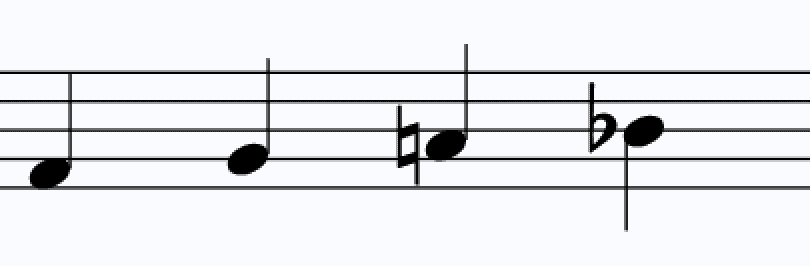

Don’t Accidentally Create A Leading Tone

Using The Dorian Mode In Harmony

Avoid: Accidentally Modulating

In line with the idea of avoiding turning the raised 6th into a leading note is the idea of an accidental modulation. Remember that while these modes are distinctive in their tone and are organised around a specific tonic, they are made up on notes that are much more typically associated with different scales.

The C Dorian, for example, is effectively a Bb major scale with a new tonic. This means that when you’re using chords (such as the diminished chord VI, or chord VII if you look from the Bb perspective), you could make your harmonic sequence sound like it isn’t actually in the Dorian mode at all.

Do: Use It In Jazz Harmony

As mentioned both above and below, the Dorian mode has a strong association with jazz. It can create some interesting melodies, but the versatility of the Dorian is best for harmony. There are a lot of ways you can use the Dorian to add interesting extensions to your chords, for example. Chord VII is now a VIImaj7 if you add the A natural on top of a Bb chord. This is a long way from the jarring diminished 7th most minor scales would bring you. The most interesting way of using it, however, is when you introduce it into the 12 bar blues pattern.

Imagine you’re in B Dorian. You’ve got access to a G# that you wouldn’t have in the normal minor scale, so you can use it to your advantage during a 12-bar blues pattern. When you move to E7 (a chord that you can very early construct down at the first frets of the guitar by placing your 3rd finger on fret 2 of the 5th string and your 4th finger on fret 1 of the 3rd string), you can give the chord pattern an interesting sound that wouldn’t work quite as well with a major seventh.

Use The Dorian For Jazz Harmony

Do: Use The Major Chord IV

This is both the most important thing about the Dorian mode, and the most common way it gets used. It’s impossible to count how many songs use this technique, but it works well for all of them. If you start off by playing a minor chord sequence which sounds minor, and add a Dorian inflection right at the very end, it gives off an incredibly unique and recognisable tone, which adds just enough flair to keep things interesting without getting crazy.

For example, a chord sequence in C minor moving from chord I, to III, to VII, to IV would be Cm, Eb, Bb, F. You’d be expecting that F chord at the end to be a minor version, but as we hadn’t heard the A in any form so far, when we hear it as a natural note (therefore creating a major chord) its unexpected, but not unpleasant.

Use The Major Version Of Chord IV

Do: Borrow Chords For Effect

Speaking of borrowed chords, don’t feel like you can’t mix and match the harmonic content of a variety of modes if you want to. You could be playing in the darkest Locrian mode in the world, but if a chord that is typically associated to the Dorian mode sounds correct as your next chord, then slot it right in.

The same works the other way around; you could be firmly in the Dorian mode throughout an entire piece, but if chord IV sounds better with a flattened seventh above it that one single time, then you can absolutely do that.

Do: Use The Mixolydian Chord VII

It seems counterintuitive almost to call a chord in the Dorian mode a Mixolydian chord, but any minor scale with a seventh that isn’t raised gives off a sound that we would typically associate to the Mixolydian mode.

As using this chord in this place avoids the leading tone, your move from chord I to VII is smooth and not dissonant. The Dorian mode happens to have the exact same harmonic movement within it (but it isn’t called a ‘Dorian 7th’ simply because it doesn’t define the scale), so make the most of it.

Avoid: Accidentally Using Diminished Chord VI

There are a variety of chords in the Dorian mode that might not sound quite right if you use them out of place. For example, chord IV with the major third could be particularly jarring if you’ve already established the minor 6th at some point in your piece.

However, there is one much more jarring chord that you’ll probably only want to use if you know its purpose and exactly how it’s going to sound. Chord VI, thanks to its raised A, is a diminished chord in its triadic form. That means that instead of having a nice fifth above it, you get a tritone interval between A and Eb. If not used carefully, this can create a very strong dissonance. There is a real tritones were once illegal.

Examples Of The Dorian Mode In Use

- Eleanor Rigby – The Beatles. Arguably the most famous song ever written in the Dorian mode is The Beatles’ ‘Eleanor Rigby’, and it’s actually only partially Dorian. The chord sequence itself is primary an alteration from E minor to C major, which is a simply minor alternation. The genius of The Beatles comes from their use of melody. Despite an Aeolian chord sequence, a huge amount of the cello melodies (and some parts of the vocal line) actually bring a C# into the melody line, creating a clash which doesn’t actually clash at all against the chord sequence. This is not only another testament to the compositional skill of the band, but also proof of how diverse and subtle the Dorian mode can be when used correctly.

- So What – Miles Davis. Another of the most famous uses of the Dorian mode comes from legendary jazz trumpet player Miles Davis. Sort of. His pianist at the time was Bill Evans, who we mentioned above, and his harmonic style has long since between a subject of study to many music scholars. His chord sequences here are both in the Dorian mode. The head section is an AABA structure, with the A section in D Dorian and the B in Eb Dorian. Using the so-called ‘So What’ chords in the A section, Evans moves from Em7add4 to Dm7add4 seamlessly. These notes are all common to C major enharmonically, but the D is the very clear tonic here, making this is distinctive use of the Dorian mode. Basically the same approach can be found in the B section.

- Mad World – Tears For Fears. The chord sequence found in Tears For Fears’ ‘Mad World’ is actually an exact version of one of the most common ways the Dorian mode can make its way into harmony as discussed above. The exact chord sequence in this track is Fm, Ab, Eb, Bb. Those first three chords have a very clear and simple implication of F minor, and they sound like it too. However, what they don’t do, is introduce us to D (flattened or natural) so we don’t know what it is going to be. When we reach the Bb at the end, it is revealed that the D is actually natural, making the chord major and giving the chord sequence that very distinctive Dorian flair.

Different Types Of The Dorian Mode

- Dorian b2. The Dorian b2 is exactly what it looks like. It’s the Dorian mode but with its 2nd flattened. This makes it one note away from being a standard Dorian scale, but also one note away from being a standard Phrygian scale. As such, it is also sometimes called the Phrygian #6. The obvious most interesting thing about this scale is that your opening note is now a minor 2nd, which is incredibly distinctive and gives the mode an even darker feel than it already had. You want to make sure you don’t accidentally avoid the #6th and make the scale feel like a typical Phrygian mode, though. Be aware of the fact that the scale now has two tritone intervals (Db-G and Eb-A), but also allow it to expand your harmony. If you were playing C and G together and moved up by one note, you’d reach D and Ab. This now becomes Db and A, which just about sums up how much new harmonic movement you have access to.

- Dorian #4. Just like the mode discussed above, the Dorian #4 is just as obvious as it seems. Take your standard Dorian mode and sharpen the fourth, and you’ve got the Dorian #4. If you’ve been exploring the other entries into our guides to modes, you’ll be familiar with the Lydian mode, which is simply a major scale with a #4th. As such, this version of the Dorian has a lot of similarity to the Lydian Diminished mode. The main benefits of this mode is that chord II can be major, which gives you access to some great flamenco sounds; the augmented 2nd leap between the minor 3rd and the sharp 4th; and the removal of the potentially jarring whole-tone run that sits in the middle of the scale.

- Dorian Bebop. Now we can move into the less obvious version of the Dorian mode. The ‘bebop’ version of the Dorian mode takes a lot of influence from the b2 version of the scale, and is in fact made up of the exact same notes. The difference with the bebop variant is the presence of both the minor and major 3rd. This creates a lot of interesting implications. First of all, it renders the trademark darkness of the Dorian mode almost indecipherable. How can a scale be both major and minor? It also creates an innate run of chromaticism from the b3rd, through the major 3rd, and reaching the 4th. There is no blues note tritone afterwards for some reason, but you’ve got all the blue notes you could ever want thanks to that major 3rd sneaking its way in there.

Conclusion

The Dorian mode is one of the easiest modes to get the hang of. Its similarity to the standard minor mode makes it easy to get the hang of, and the use of its distinctive intervals mean you can use it in harmony without much worry that it’ll sound dissonant. The main things I’d suggest you be on the lookout for are:

- The use of the major chord IV. Even if you aren’t actively using the Dorian mode in your playing, a sudden interjections from chord IV in its major form can be a huge addition to your sound.

- Avoid accidentally modulating (if you don’t want to). This could happen both harmonically and melodically, so make sure you don’t make it seem like a note that isn’t your tonic is your tonic.

- Play on its half-darkness and half-brightness. This is the only common mode which mixes a note which gives off a distinct darkness (the minor 3rd) which one that suggests brightness (the major 6th). You can make really creative use of this in certain situations.