If you’re looking for some smooth-sounding chords with a rich sound, our major seventh chords have you covered. The Gmaj7 chord, in particular, is a great chord for getting started with these seventh chords, as well as getting your feet wet with some more challenging barre chords. As you read on, we’ll cover how the Gmaj7 chord is played, and how it functions, so you can apply it to other seventh chords. Let’s dive in!

Contents

How to Play the Gmaj7 Chord

The Gmaj7 chord comes in a few different forms, otherwise known as chord variations. There are a few different reasons why you would use one chord variation over another. Firstly, you might choose a chord depending on your skill level. Sometimes chords may feel a little too awkward, or you just haven’t developed the finger strength to hold it, in which case, it might be easier to just play a more simplified version. Another reason might be because of how it works within a chord progression. For instance, if your chords are all hanging around the open note position, why play a chord on the 7th fret? It might not always make the most sense, in which case, you’ll want to go with something a bit easier, or that might flow better. You might choose a different chord variation because of how it sounds, as different variations bring out different tonal qualities. However, it all comes down to what you prefer, and what works best for you. You can’t go wrong!

Let’s try out a few of these different variations:

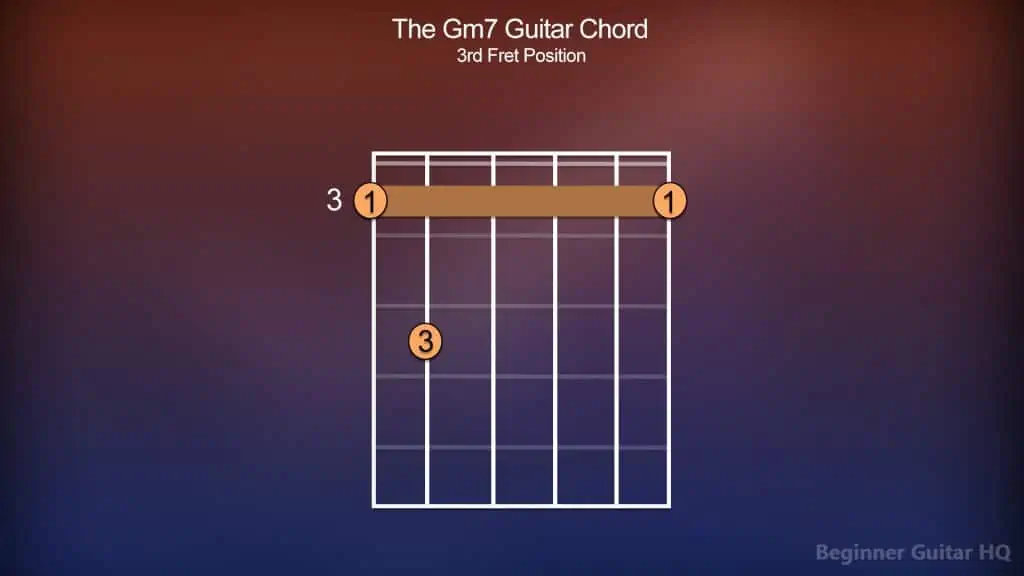

Chord chart of the Gmaj7 Guitar Chord from the open note position.

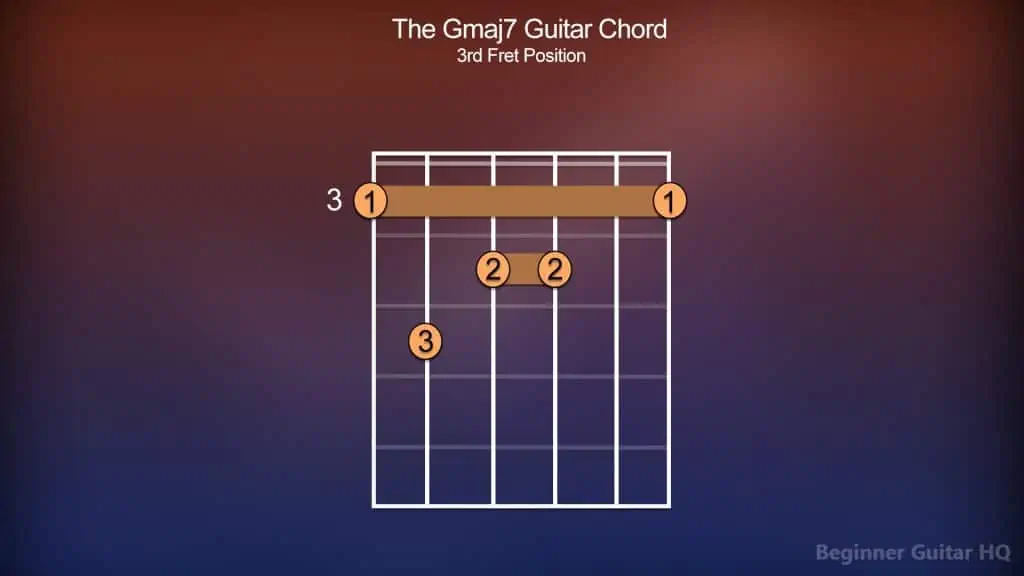

Chord chart of the Gmaj7 Guitar Chord from the third fret position.

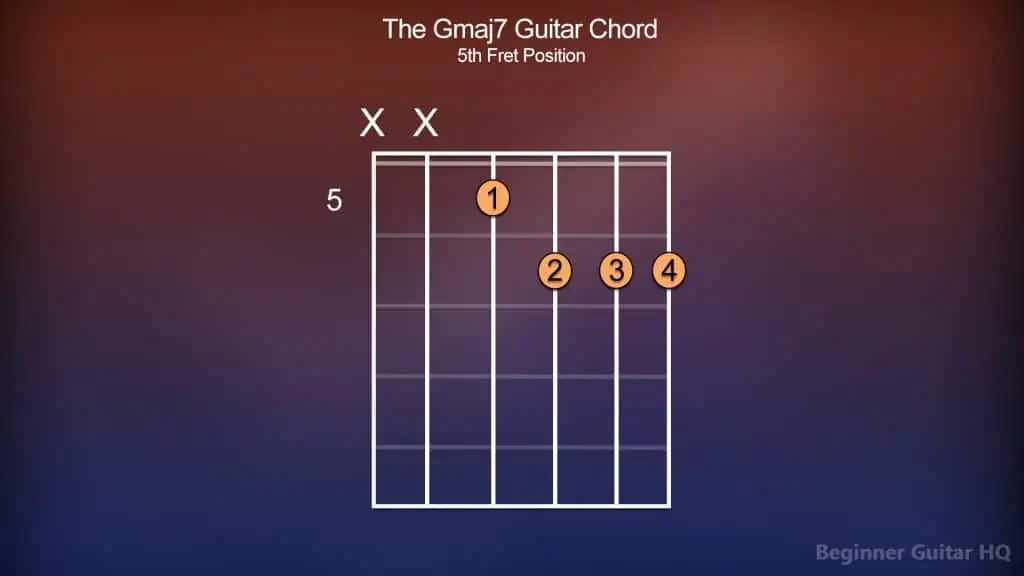

Chord chart of the Gmaj7 Guitar Chord from the fifth fret position.

Trouble With Chord Charts?

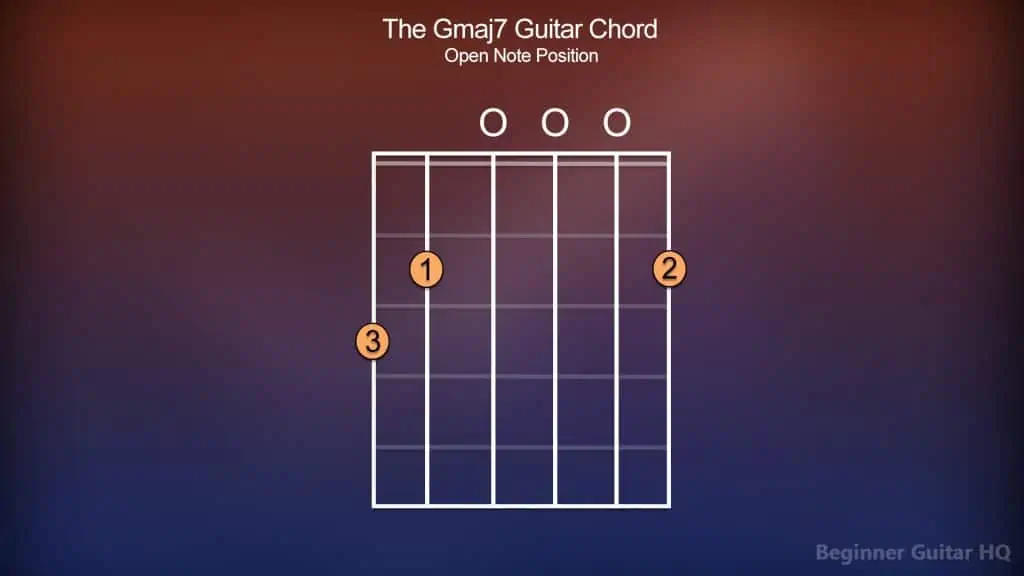

Chord charts, at first glance, might seem somewhat overwhelming. Don’t fret! Learning chord charts are very simple, and will serve you for years to come! Let’s begin by bringing our attention to the big rectangular box, containing a collection of vertical and horizontal lines. This represents our fretboard. Each vertical line represents a different string on the guitar. Starting from the left to the right, we have our low E, A, D, G, B, and high E strings. Each horizontal line, however, separates one fret from the next.

Within the frets and over the strings, you’ll see circles containing a number anywhere from 1 – 4. These numbers represent our different fingers, and where they’re supposed to go on the fretboard. The number 1 represents our index finger. The number 2 represents our middle finger. The number 3 represents our ring finger. Finally, the number 4 represents our pinky finger. In some cases, you might notice a long bar stretching across a number of strings. This is called a “barre”. To form a barre, you simply drape your index finger across multiple strings along an individual fret, then apply pressure. This will likely feel uncomfortable at first, but over time it will get easier!

Next, when you look above the fretboard, particularly the strings, you may notice an “O” or an “X” present. If there’s an “O”, that indicates that you’re supposed to play an open note as part of the chord (a string to be played, but not fretted). If, however, there’s an “X” present, that indicates a string not to be played to form our chord. Off to the left of the fretboard, there may be a number present. If there’s a number, this indicates your starting fret in forming our chord. If there is no number present, then it’s generally implied that you’re starting from the open note position. That’s all there is to it!

Breakdown of the Gmaj7 chord

The major seventh chord is widely used across Jazz, Country Rock, Funk, and even Disco music. Giving off a rich, smooth, and airy harmony, these chords can be a lot of fun to play, as much as they are to listen to. In fact, many popular artists have included these chords in their widely known hits, such as “The Rolling Stones – (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”, “Jimi Hendrix’s – Purple Haze”, and even “The Beatles – Something”. We know that they sound great, but how exactly do they work? To understand our Gmaj7 chord a little better, we’ll cover three fundamental elements: the key, scale, and triad.

Let’s begin with the key. The key can be described as a grouping of musical pitches, no different than what you’d find in a scale. How are these pitches defined? That’s where our key signature comes into play. Every key contains its own key signature. The key signature often spotted after the clef on a piece of sheet music, is visually represented by a collection of sharps (#) and flats (b). A note that is marked as sharp, is to be raised by a semitone. However, a note that is marked flat, is to be lowered by a semitone. So how do we find out the key signature of a corresponding key? That’s where it can help to consult the circle of fifths.

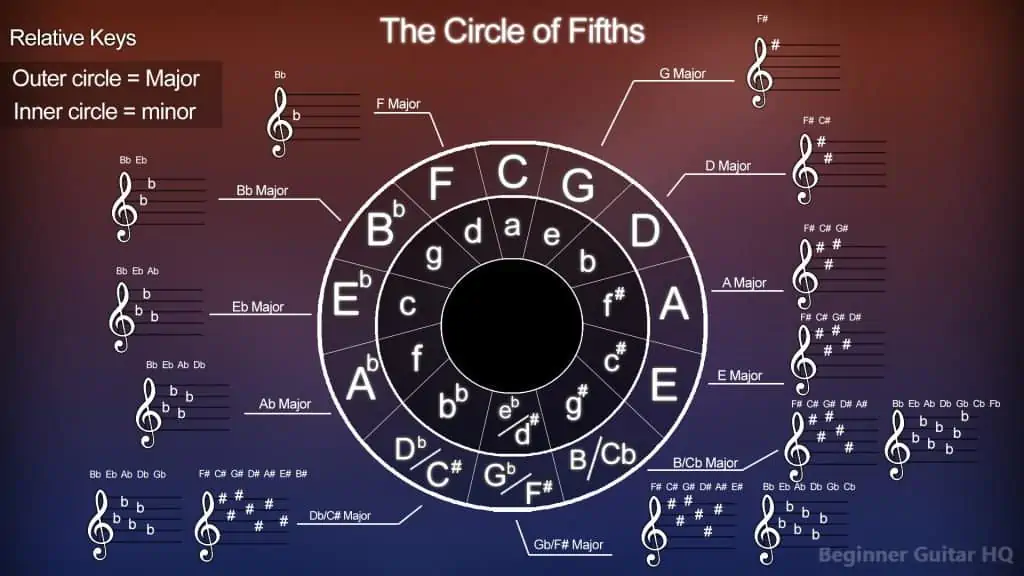

Diagram of the circle of fifths, displaying all of the most commonly used keys.

The circle of fifths is a wheel-shaped diagram displaying all of the most commonly used keys and their corresponding key signatures. Within the circle, you’ll notice two rings. The outer ring houses all of our major keys, while the inner ring houses all of our relative minor keys (keys with a different root note, but share the same key signature). Starting from C, as you go clockwise around the wheel, you’ll notice that every key gains an additional sharp to its key signature. On the other end of the spectrum, starting from C, you’ll notice every key gains an additional flat to its key signature. Since, however, we’re in the key of G major, we’ll be focusing on the right half of the wheel.

So, how do we determine the sharps in our key? We use a simple acronym: FCGDAEB. This stands for:

“Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle”

Each word within this little saying represents a different note that is to be made sharp, in sequence. Let’s take a look at how this pattern appears within the circle of fifths:

C = No sharps or flats.

G = F#

D = F#, C#

A = F#, C#, G#

E = F#, C#, G#, D#

B = F#, C#, G#, D#, A#

F# = F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#

C# = F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, B#

Using the circle of fifths, we can see how many sharps each key has with ease. For instance, if we knew that A major contains three sharps in its key signature, using our fingers, we’d go “Father, Charles, Goes…” therefore, the sharps in the key of A major are F#, C#, and G#. Let’s try again with F# major, containing six sharps. Using our fingers, we’d go “Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends…” therefore, the sharps in the key of F# major are F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, and E#.

If you are more comfortable with the opposite side of the wheel, and you want to easily figure out the key signature on your weaker side, then you just need to remember the number 7. For instance, let’s say we wanted to figure out the key signature of Eb major. Now, turning to E major, knowing that we have four sharps in that key, we take our number 7 and subtract 4, giving us 3. Therefore, the key signature of Eb major has three flats.

Different from before, how we used “FCGDAEB” to figure out the key signature, in a flat key we reverse it to BEADGCF. This stands for:

“Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’, Father”

Using the same method as before, we can deduce that the three flats in the key of Eb major are Bb, Eb, and Ab.

Moving on, since we’re in the key of G major, we only have one sharp, F#. Let’s throw our G major scale together:

G > A > B > C > D > E > F# > G

Our major scales always follow a strict set of tones (T) and semitones (S) that give the scale its warm and happy vibe. The sequence appears as follows:

T > T > S > T > T > T > S

As you can see, the third interval from B > C is a semitone apart, and the sixth interval from E > F# is a tone apart, shifting F# > G a semitone closer. It never fails!

Now, let’s try playing our G major scale:

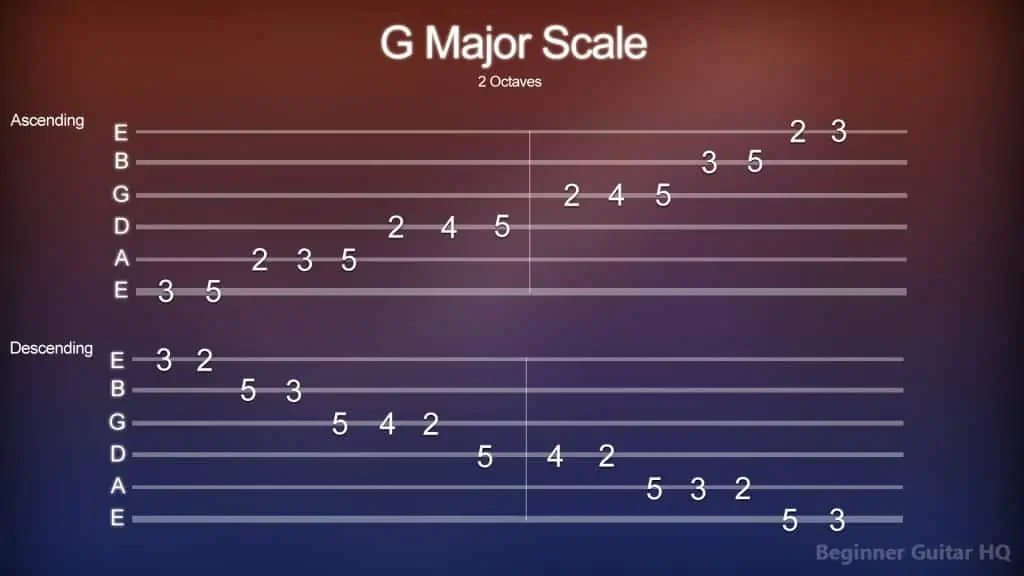

Guitar tablature of our G major scale, ascending and descending two octaves.

Trouble With Tablature?

Guitar tablature, also known as “tab”, is an easy and effective means to write, share, and learn some of your favorite songs and exercises. Let’s bring our attention to the six horizontal lines you see before you. Each of these lines represents a different string on the guitar. From the bottom to the top we have our low E, A, D, G, B, and high E strings.

On the strings, you’ll see some numbers indicating the fret you’re to play. For instance, if you see the number 3 on the low E string, you’re to play the third fret on the low E string. If you see the number 5 on the D string, you’re to play the fifth fret on that corresponding string, and so on. If, however, you see the number 0 on any string, this implies that you’re to play an open note (a string to be played, but not fretted). That’s all there is to it!

Tablature can be an excellent tool for self-taught guitarists who don’t have an extensive musical background. However, there are some minor drawbacks to be aware of. Firstly, the quality of the tablature varies from tab to tab. Since most tabs, nowadays, you can find online, you won’t always find ones containing the most detail. In situations like this, it’s either time to search for a different tab or work on filling in the blanks using your ear. Fortunately enough, there are plenty of excellent tabs out there that provide a lot of instruction for the guitarist. Here are some of the symbols used within tablature:

H = Hammer-on

P = Pull-off

B = Bend

X = Mute

PM = Palm Mute

\ = Slide Down

/ = Slide Up

~~~ = Vibrato

One final note; it’s important to exercise good playing habits. The habit we’re talking about in particular is good fingerwork. Guitar tablature and sheet music won’t often if ever tell you where you should be placing your fingers. Good fingerwork can make all the difference in making things easier to play and keeping a steady flow. Sometimes when it comes to learning the guitar, we get so excited that we gloss over some of the important fundamentals, to only have to unlearn bad habits later on. To avoid this, it’s best to develop proper playing technique, posture, and patience. Practicing spider exercises, or even with a metronome can help you improve on this.

Scale Degrees

Within our G major scale, every note plays an important role. We can call these notes our scale degrees. Every degree of our scale has a unique name that helps musicians refer to them. Taking our G major scale, here are our various degrees:

G = Tonic (1st Degree)

A = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

B = Mediant (3rd Degree)

C = Subdominant (4th Degree)

D = Dominant (5th Degree)

E = Submediant (6th Degree)

F# = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

G = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

Let’s talk about each degree in a little more depth – our 1st degree, the tonic, is our tonal center and home where things tend to resolve. Our 2nd degree, the supertonic, shares two notes within its triad as our 4th degree, making it a weak predominant chord. Moving up, the 3rd degree, the mediant, shares two notes with the tonic triad, making it an excellent degree for drawing out the tonic further. Upwards, we have our tense 4th degree, the subdominant. The 4th degree only shares one note with our tonic’s triad, G. Building on this tension, we’re on the 5th degree, the dominant. This is the most important degree, next to our tonic, carrying the most tension. Typically, from our dominant, we’ll resolve home to our tonic – but we’ll keep going upwards. Next, we have our submediant, the sixth degree. The submediant acts as a predominant chord, sharing two notes with our subdominant triad. Next, we have our 7th degree, the leading tone. Our leading tone, important in forming our 7th chords, also holds a lot of tension. In fact, try playing the C major scale and ending on B; your ears will want to hear it resolve to C. Finally, we’re back at our 1st degree, the tonic, one octave higher from where we began.

Triads

A triad is a grouping of three notes played in unison. To form a major triad, we need to take our tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees (1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees) and stack them on top of each other. In G major, this gives us the notes: G, B, and D.

Did you know that major triads contain their own specific intervals?

- Major 3rd – Between the 1st and 3rd degrees. G > B.

- Minor 3rd – Between the 3rd and 5th degrees. B > D.

- Perfect 5th – Between the 1st and 5th degrees. G > D.

To make our G major seventh chord, however, we only need to take our existing triad of notes, and stack the 7th degree of our G major scale on top! This gives us the notes: G, B, D, and F#.

Finding Chords Compatible With G Major

Making chord progressions can be a challenge at times, especially making one we enjoy. Fortunately, there’s a way of making this process a little easier! It involves taking our G major scale, and stacking triads on every degree of the scale:

G Major = G, B, D (Tonic/1st Degree)

A minor = A, C, E (Supertonic/2nd Degree)

B minor = B, D, F# (Mediant/3rd Degree)

C Major = C, E, G (Subdominant/4th Degree)

D Major = D, F#, A (Dominant/5th Degree)

E minor = E, G, B (Submediant/6th Degree)

F# diminished = F#, A, C (Leading Tone/7th Degree)

These are all of the chords compatible in the key of G major!

GMaj7 to Gmin7

We’ve gone over quite a bit about the key of G major, and our Gmaj7 chord, but what about its minor counterpart, Gmin7? Firstly, Gmin7 has a different key signature than Gmaj7, as they’re in a parallel key relationship. This means that they share the same tonic, but have different key signatures; G major has one sharp, while G minor has two flats. This is different than the relative key relationship that G major has to E minor, where they have different tonics, but share the same key signature.

Using the method from earlier, we know that G minor has the flats, Bb, and Eb in its key signature. Let’s take a look at the G minor scale now:

G > A > Bb > C > D > Eb > F > G

Minor scales, much in the way major scales do, have their own set pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S). Let’s take a look at the sequence:

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

As you can see above, the second interval from A > Bb is a semitone apart, but Bb > C is a tone apart. The same occurs with D > Eb being a semitone apart, while Eb > F is a tone apart. It will always follow this pattern!

Now, taking our G minor scale, let’s form a G minor triad. To do so, we yet again take our tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees (1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees) of our scale and stack them on top of each other. This gives us the notes: G, Bb, and D.

Minor triads also contain their own specific intervals:

- Minor 3rd – Between the 1st and 3rd degrees. G > Bb.

- Major 3rd – Between the 3rd and 5th degrees. Bb > D.

- Perfect 5th – Between the 1st and 5th degrees. G > D.

Do you see the difference? It’s reversed! The 1st interval within our minor triad is a minor 3rd, while in a major triad it’s a major 3rd. The 2nd interval within our minor triad is a major 3rd, while in a major triad it’s a minor 3rd. The perfect 5th remains the same in both.

If want to convert our G minor triad to a G minor seventh triad, we simply stack the seventh degree of our scale on top, giving us the notes: G, Bb, D, and F.

Now, let’s try playing our Gm7 chord:

Chord chart of the Gm7 Guitar Chord from the third fret position.

Conclusion

That’s all there is to it! Now, you can get started with your newly found Gmaj7 chord. Adding new chords to your repertoire can be an excellent way of combating writer’s block, as well as spicing up your practice routine. It’s always good to find new ways of challenging yourself so that you can develop as a guitarist. The more tools you have in your arsenal, the more approaches you can take to songwriting or improvisation.

It’s always encouraged that you learn more about the fretboard to open your third eye to more possibilities in how things can be played. In fact, learning the CAGED system can be a great way to begin that journey. As they say, however, music theory is an asset, but not always needed! In fact, some of the great and successful musicians we hear about didn’t know a lick about music theory. However you decide to grow as a musician, make sure you’re at least having fun along the way. Keep on rockin’.