At a jam session, you might hear the singer ask the band to play a song in something like the “key of G” or the “key of D minor”. But what exactly are keys?

Simply put, keys are a collection of notes and chords that sound good together. A lot of guitar players think of them as just a handful major and minor chords. But keys are a bit more complicated than that, as we’ll see in this guide…

Building Keys

If you’re a rhythm guitar player, chances are you’ll be working mainly with chords. But it’s still helpful to look at the individual notes that make up keys. This way, you’ll know exactly how they work together to form lead and rhythm guitar parts.

Notes

In Western music, there are 12 different notes you can play. Each note is a half step (also called a half tone or semitone) higher than the previous one. Chromatic scales contain all 12 notes in a sequence. For example, the C chromatic scale is: C, C♯/D♭, D, D♯/E♭, E, F, F♯/G♭, G, G♯/A♭, A, A♯/B♭, B. You can then play the scale an octave higher, starting with the next C.

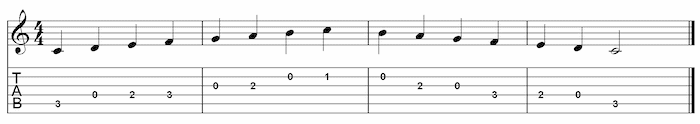

The C chromatic scale for guitar. As you can see (in standard notation especially), there are no sharps or flats between E and F or B and C (Created using Flat).

You may be wondering why notes like C♯ and D♭are listed together. This is because they are enharmonic equivalents.They’re the same note, written differently depending on whether there’s another C or D note in the scale.

What does this all mean for guitar? Well, for every half step, you slide up one fret on the fretboard. For example, in the C chromatic scale, you could start on the 1st fret of the 2nd string and play every note to the 13th fret. However, it’s more common to stay in the same position on the guitar neck (ex: the 1st-4th frets) and play notes on different strings.

Technically, you could write a guitar song based on a chromatic scale. But it would sound pretty chaotic. Instead, most guitar keys are based on diatonic scales. They highlight 7 notes that create the most consonance (pleasant sounds).

Aside from 2 half steps, diatonic scales contain 5 whole steps (also called tones or whole tones). On a guitar fretboard, notes that are a whole step apart are two frets away from each other.

Major scales are diatonic scales with the following pattern: Whole step, Whole step, Half step, Whole step, Whole step, Whole step, Half step (or WWHWWWH).

Let’s go back to the C chromatic scale. If we apply the major scale pattern, we get these notes: C D E F G A B.

The C major scale for guitar, starting on the 5th string

Keys take their name from the root note of the scale. So, if the lead singer asks for the key of C (or C major), you would use the 7 notes from the C major scale.

The same principle applies to the (natural) minor scale, but in a different pattern –– WHWWHWW. So, in the key of C minor, you would get C D E♭ F G A♭B♭.

The C minor scale for guitar, starting on the 6th string .

One of the awesome things about guitar is that you can play songs in any key –– from D major to E minor to G♯ harmonic minor (a non-diatonic minor scale with a natural 7th note) to B♭ melodic minor (a non-diatonic minor scale with a natural 6th and 7th).

Yet, in standard guitar tuning, some keys are easier to play than others. For example, in the key of C, you can play the root chord (C major) in open position. However, in Cm, you either need to use a barre chord or place a capo on the 3rd fret and transpose your chord voicings to the key of Am.

The most common major guitar keys are G, C, A and D. The most common minor guitar keys are Am and Em.

Chords

Across all keys, guitar chords (often) consist of simple triads. Triads have 3 notes from the parent diatonic scale:

- The root

- The 3rd

- The 5th

Depending on the type of triad, the 3rd and 5th notes can either be natural (not lowered or raised) or flatted (lowered by one or more half tones). The 3 main types are:

- Major: 1st, 3rd and 5th notes from the major scale.

- Minor (m): 1st, ♭3rd and 5th.

- Diminished (dim): 1st, ♭3rd and ♭5th.

Let’s go back to C major –– C D E F G A B. The C chord has the notes C, E and G. Cm has C, E♭ and G, while Cdim has C, E♭ and G♭.

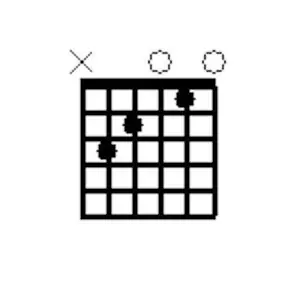

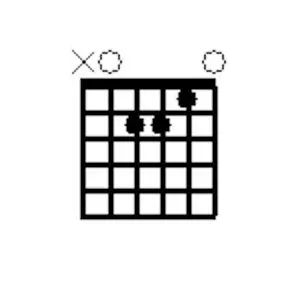

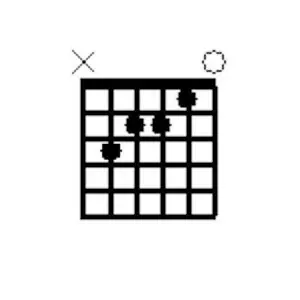

Barred C major, C minor and C diminished guitar chords. Note how the root note on the 3rd string stays the same, while the 3rd note (2nd string) and 5th note (4th string) change.

All guitar keys contain 3 major chords, 3 minor chords and 1 diminished chord. They’re usually written as roman numerals, with uppercase numerals (ex: IV) indicating a major chord and lowercase numerals (ex: iv) indicating a minor. Diminished chords have lowercase numerals with a degree sign (ex: iv˚).

The pattern for major keys is:

- Major (I)

- Minor (ii)

- Minor (iii)

- Major (IV)

- Major (V)

- Minor (vi)

- Diminished (vii˚)

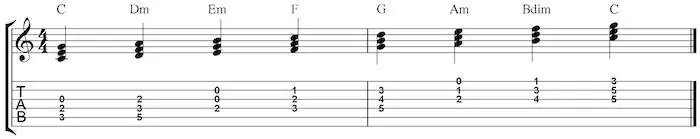

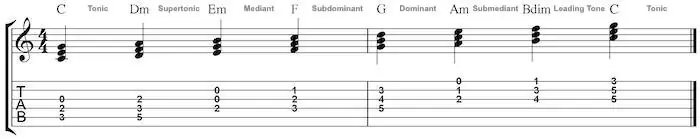

In C, these chords would be C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am and Bdim.

Key of C guitar chords

The pattern for minor keys is:

- Minor (i)

- Diminished (ii˚)

- Major (III)

- Minor (iv)

- Minor (v)

- Major (VI)

- Major (VII)

In Cm, these chords would be Cm, Ddim, E♭, Fm, Gm, A♭, B♭.

Especially in major keys, diminished chords sound unstable. It’s not that the notes are wrong. For example, Bdim contains the root (B), ♭3rd (D) and ♭5th (F) from the parent B major scale (B C♯ D♯ E F♯ G♯ A♯). These notes belong to the C major scale too –– as the 7th, 2nd and 4th scale degrees.

The problem is that the root and ♭5th of diminished chords create a tritone. Also called “the devil’s interval,” this is the most dissonant (clashing) tone in Western music. Outside jazz circles, most guitar players ignore the diminished and focus on the three majors and minors.

Identifying Keys

Now that you know what keys are, the next step is to figure out how to identify the keys of songs.

First and last chords

One of the easiest ways to name keys is to look at the first and last chord in a progression. Let’s take “Folsom Prison Blues” by Johnny Cash. The chord progression is E A E B7. This suggests that the song is in the key of E.

The full guitar lesson for “Folsom Prison Blues”.

B7 is built on a regular B chord, so let’s ignore the ♭7th note for now. Based on the E major scale and pattern for major keys, the key of E chords are E F♯m G♯m A B C♯m D♯dim E. Folsom Prison fits perfectly, as a I IV I V 12 bar blues progression.

This strategy works most of the time. However, root chords don’t always start or end a progression. That’s why it’s useful to consider all of the major and minor voicings as a whole.

Major and minor chords

One way I like to figure out guitar keys is to look at each individual chord and see if it works as the root chord, considering which of the other chords are majors and minors.

Let’s look at “Sunday Morning” by Maroon 5 –– Dm9 G13 Cmaj9. Ignoring the extensions, let’s treat the chords as Dm G and C.

The full guitar lesson for Maroon 5’s “Sunday Morning”.

If the song is in the key of Dm, we would expect these chords –– Dm Edim F Gm Am B C. C works here as the VII chord. But the song has a G instead of a Gm. So, Dm probably isn’t the root chord.

Now, let’s look at the key of G –– G Am Bm C D Em F♯dim. Again, the C works here as a IV chord. But the Dm doesn’t fit.

Finally, we have the key of C –– C Dm Em F G Am Bdim C. The Dm and G both work. Therefore, Sunday Morning is in the key of C, with a jazzy ii-V-I progression.

Sometimes a guitar chord progression could work in two or more keys. For example in “Every Breath You Take” by The Police, the chords are A♭ Fm D♭ E♭. This could be a I vi IV V progression in A♭ (A♭ B♭m Cm D♭ E♭ Fm Gdim) or a III i VI VII progression in Fm (Fm Gdim A♭ B♭m Cm D♭ E♭). Still, since the progression starts and ends with a major chord, the key of A♭ makes more sense.

7th chords

If the song has different types of 7th chords, you can often use them to find the key. This is because the type of 7th extension a chord has usually depends on whichever scale degree it’s based on.

Major 7ths are major chords with an added 7th scale degree. Dominant 7ths are majors with a ♭7th, while minor 7ths are minor chords with a ♭7th scale degree. Half-diminished 7ths (also called minor 7th flat 5s) also contain a ♭7th.

With a C root note, these chords become…

- Cmaj7 (CEGB)

- C7 (CEGB♭)

- Cm7 (CE♭GB♭)

- Cø7 (CE♭G♭B♭)

Barred Cmaj7, C7, Cm7 and Cø7 guitar chords.

For major keys, the pattern is:

- Major 7th (Imaj7)

- Minor 7th (iim7)

- Minor 7th (iiim7)

- Major 7th (IVmaj7)

- Dominant 7th (V7)

- Minor 7th (vim7)

- Half-diminished 7th (viiø7)

For minor keys, the pattern is:

- Minor 7th (im7)

- Half-diminished 7th (iiø7)

- Major 7th (IIImaj7)

- Minor 7th (ivm7)

- Minor 7th (vm7)

- Major 7th (VImaj7)

- Dominant 7th (VII7)

Let’s take the jazz standard “Autumn Leaves”. It can be played in many different keys. But let’s stick to these chords –– Em7 A7 Dmaj7 Gmaj7 C♯ø7 Bm.

The full guitar lesson for “Autumn Leaves”.

There’s a lot of chords here. But the A7 and the C♯ø7 stand out from the regular major and minor 7ths. Because the song starts and ends on a minor, this suggests that we’re working in a minor key. So, A7 is the VII chord and C♯ø7 is the ii chord. This suggests that “Autumn Leaves” is in the key of Bm (Bm7 C♯ø7 Dmaj7 Em7 F♯m7 Gmaj7 A7).

A word of warning though –– this method doesn’t usually work in blues songs, where all (or almost all) the guitar chords are dominant 7ths.

Circle of fifths

Finally, if your guitar parts are written in standard notation, the easiest way to find their keys is to look at the number of sharps or flats beside the treble clef.

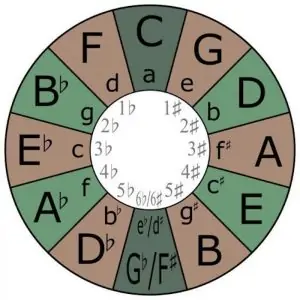

This principle is based on the circle of fifths diagram. In the outer circle, it starts with C major at the top. Then, it moves clockwise in ascending 5th intervals (the V chord from the previous chord’s major key). For example, in the key of C, G (the next note in the circle) is the V chord. G is followed by D (the V chord in the key of G), which is followed by A, and so on.

If you move counterclockwise (or anti-clockwise), you get descending 5th intervals (the IV chord in each major key). F is the IV chord in the key of C, B♭ is the IV chord in F, and so on.

As you know, the key of C has no sharps or flats. But for each step clockwise, you add 1 sharp to your treble clef. For example, the key of G has 1 sharp (F♯), the key of D has 2 sharps (F♯ and C♯), etc. For each step counterclockwise, you add 1 flat. For example, the key of F has 1 flat (B♭), the key of B♭ has 2 (B♭ and E♭), and so on.

The circle of fifths diagram, without the final 7♭ key (C♭major/A♭ minor) and 7♯ key (C♯ major/A♯ minor).

The inner circle of the diagram contains relative minors –– the vi chords of each major key, whose parent scales contain the same number of sharps and flats. For example, Am is the relative minor of C, and contains all natural notes. Moving forward, Em (the relative minor of G and the v chord in the key of Am) has 1 sharp. Moving backward, Dm (the relative minor of F and the iv chord in the key of Am) has 1 flat. And so forth.

If you go far enough around the Circle of Fifths, you’ll end up with four strange keys…

- F♯ major/D♯ minor: 6 sharps, including E♯

- C♯ major/A♯ minor: 7 sharps, including E♯ and B♯

- G♭major/E♭ minor: 6 flats, including C♭

- C♭major/A♭ minor: 7 flats, including C♭ and F♭

None of these notes actually exist. B♯ is a C note, C♭is B, E♯ is F and F♭is E. They’re only written this way because the keys already contain sharp or natural versions of the notes.

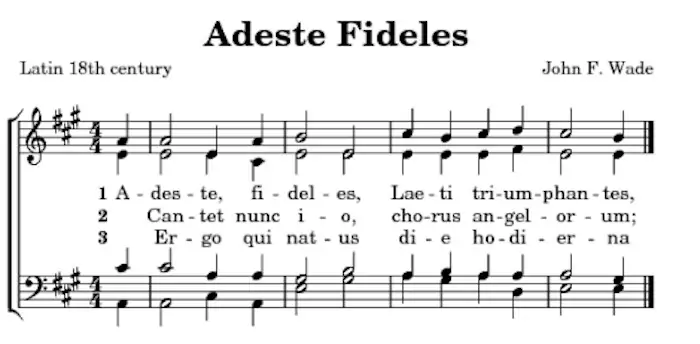

Let’s try out the circle of fifths by looking at this version of the hymn “Adeste Fideles” (“O Come All Ye Faithful”):

The opening bars to a version of “Adeste Fideles” (Cropped from “AdesteFidelesLilyPhil” by Phil Holmes / CC BY-SA 3.0).

As you can see, there are three sharps beside the treble clef. This suggests that the song is in the key of A.

Experimenting with Keys

Learning keys won’t just boost your guitar playing skills. It will also boost your songwriting skills, helping you build chord progressions for your rhythm parts and licks and solos for your lead parts.

Chord progressions

A chord progression is a group of chords from the same key, played in a specific (often repeating) order.

Most of the time, you’ll hear these chords referred to by their Roman numeral, like the “five chord” or “one chord”. You may also hear them called other names, based on their scale degree. These are the:

- Tonic (1st scale degree)

- Supertonic (2nd)

- Mediant (3rd

- Subdominant (4th)

- Dominant (5th)

- Submediant (6th)

- Subtonic (7th scale degree in minor progressions –– 1 whole step below the root)

- Leading tone (7th in major progressions –– 1 half step below the root)

Key of C guitar chords, labelled by scale degree.

Aside from the tonic, the two other most important guitar chords are the subdominant and dominant. As we saw in the circle of fifths diagram, they’re both an equal distance away from the tonic. Their diatonic scales are also similar to the tonic’s scale, with only 1 sharp or flat note difference.

Subdominants and dominants also share 1 note with the tonic chord. In the key of C for example, the F chord (FAC) shares C (CEG)’s root note, while G (GBD) shares its 5th. Still, the other two notes in each chord are different, filling out the other scale degrees in C major. This creates a rich, consonant musical texture.

In both major and minor keys, every chord shares two notes with the chord two degrees above (the mediant) or below (the submediant). For example, C shares its 3rd and 5th with Em (EGB) and its root and 3rd with Am (ACE). Mediants also mark the midpoint between the tonic and dominant, while submediants mark the midpoint between the tonic and subdominant. For these reasons, they’re often used as passing chords between the tonic and another chord.

In major keys, these two chords also play an interesting role as relative minors. The submediant is the relative minor of the tonic, while the mediant is the relative minor of the dominant. Meanwhile, the supertonic is the relative minor of the subdominant.

These chords can substitute for their relative majors, because they share similar chord and scale notes. For example, if a C (CEG) isn’t sounding right in a certain section, try an Am (ACE) instead. You can even change the minor voicing to second inversion, so the root note of the relative major is the bass note (ex: CEA –– also known as Am/C).

The Am (left) and Am/C (center) guitar chords contain the same 3 notes. However, the shape (and sound) of Am/C is more like the open C guitar chord (right).

Finally, you can take advantage of the unstable leading-tone chord by using it to resolve to the tonic. For example, Bdim (BDF) has both the leading tone (B) and supertonic (D) of the C major scale. Along with the F tritone, these tense notes create pressure, leading to a satisfying release once you return to C.

Aside from the leading tone, any chord can be used to modulate or change keys in the middle of the song. However, the most common ones are the submediant and dominant. Because they already share so many scale similarities with the original tonic, they can de-emphasize that tonal centre and shift the progression without disrupting the musical flow.

Before we move on to the lead section, let’s look at some common chord progressions. Note which ones branch beyond the subdominant and dominant:

- i VI III VII (or vi IV I V): sometimes called the “pop punk progression,” this is actually popular across genres. Ex: “Africa” by Toto (F♯m), “21 Guns” by Green Day (Dm), “Despacito” by Luis Fonsi ft. Daddy Yankee (Bm).

- I V vi IV: a popular major key progression. Ex: “Let It Be” by The Beatles (C), “I’m Yours” by Jason Mraz (A), “Afterlife” by Avenged Sevenfold (F).

- I vi IV V: also called the “50s progression”, “Heart and Soul progression” or “doo wop progression,” it features in many classic and modern songs. Ex: “Stand by Me” by Ben E. King (A), “D’yer Mak’er” by Led Zeppelin (C), “ME!” by Taylor Swift ft. Brendan Urie (C).

- I vi ii V: a slightly minor “50s progression”. Ex: “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye (E), “Fluorescent Adolescent” by The Arctic Monkeys (E).

- i iv V: a common harmonic minor progression –– hence a V instead of a v chord. Ex: “bury a friend” by Billie Eilish (Gm), “Bump Bump Bump” by B2K ft. P. Diddy (G♯m).

- i VII VI V (or vi V IV III): called the “Andalusian cadence” because of its popularity in Flamenco music, this minor progression also features in popular English songs. Ex: “Hit The Road Jack” by Ray Charles (Am), “Sultans of Swing” by Dire Straits (Dm).

- I IV I / i iv i: a simple but effective progression. Ex: “Born in the USA” by Bruce Springsteen (B), “What I Got” by Sublime (D), “I Shot the Sheriff” by Bob Marley (Gm).

- i V i / I V I: a classic progression in harmonic minor and occasionally major songs. Ex: “Paint It Black” by The Rollings Stones (Em), “All This Love” by Debarge (B♭m), “Jambalaya” by Hank Williams (C).

The pop punk progression (vi IV I V) is also nicknamed the “sensitive female chord progression”. It features in many ballads by singers like Joan Osborne (“One of Us” –– F♯m), Kelly Clarkson (“Behind These Hazel Eyes” –– F♯m) and Beyoncé ( “If I Were A Boy” –– D♯m).

For more guitar progressions in minor keys, check out this video.

Licks and solos

The best way to build lead guitar parts is to look at the parent diatonic scale. This will give you all the notes you need to craft licks, solos and other melodies.

The same scale degree principles relate here. For example, you can use the mediant and submediant to lead into the dominant and subdominant respectively, or amp up the tension by sliding from the leading tone or supertonic to the tonic. Add some legatos, bends and string skips, and boom! You might just have a memorable lick.

Each scale degree is also associated with a mode –– a diatonic scale based on the notes from the parent major scale. The 7 modes are the:

- Ionian: 1st scale degree –– same as major scale. WWHWWWH

- Dorian: 2nd scale degree. WHWWWHW

- Phrygian: HWWWHWW

- Lydian: WWWHWWH

- Mixolydian: WWHWWHW

- Aeolian: Same as natural minor scale. WHWWHWW

- Locrian: HWWHWWW

In the key of C, these modes would be C Ionian, D Dorian, E Phrygian, F Lydian, G Mixolydian, A Aeolian and B Locrian.

Each mode gives a certain feel to a solo. For example, Lydian is bright and cheerful, while Locrian is dark and tense and Dorian is melancholy but hopeful. Phrygian has a Latin feel, while Mixolydian has a blues/rock edge. Discovering the right mode for your song can add the perfect experimental feel, without straying too far from your standard major or minor keys.

This video breaks down some specific notes that you can pull out in each mode for your lead guitar parts.

There’s no magic formula for crafting the perfect lick or solo. So have fun and experiment a little. You never know what you’ll come up with!

Final Thoughts

Hopefully, this guide has helped you discover how to master guitar keys.

Whether you’re a rhythm guitar player learning new chords, a lead guitar player jamming with friends or a songwriter working on your first composition, having a solid understanding of keys will help you take your skills to the next level.

Rock on!