Nothing is quite as distinctly pleasing as the pentatonic scale in terms of sound, and playability.

Many popular songs like “John Newton – Amazing Grace”, “Led Zeppelin – Stairway to Heaven”, and even “Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Can’t Stop” all use this scale. So how can you start? As you read on, we will cover how to play them, and how they work! Let’s dive in!

Contents

How to Play the Major Pentatonic Scale

The major pentatonic scale not only sounds awesome but is often recommended to beginners based on its simplicity! Let’s tackle some of these pentatonic scales so that you can start practicing them right away!

Guitar tab of the A Major Pentatonic Scale

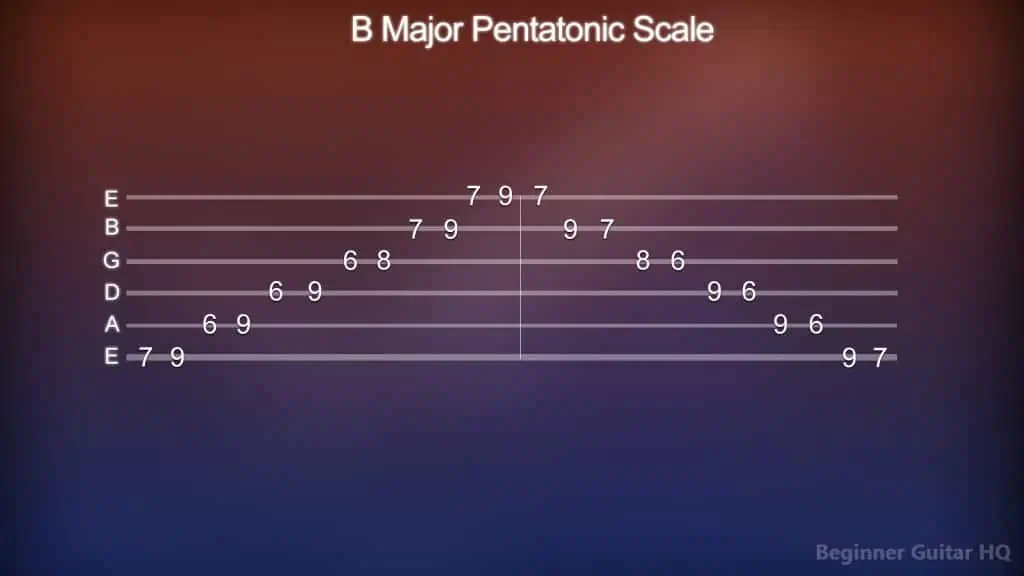

Guitar tab of the B Major Pentatonic Scale

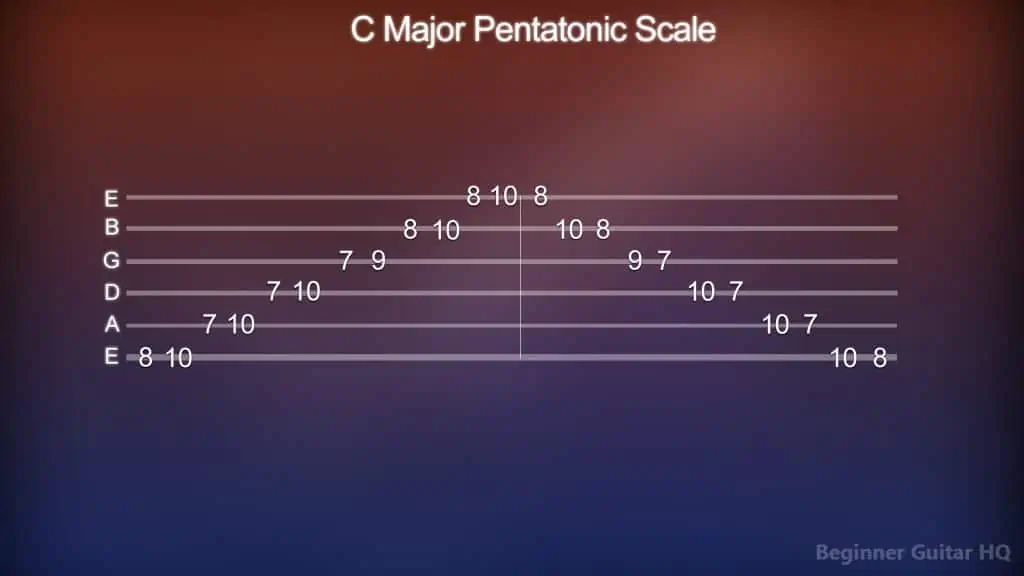

Guitar tab of the C Major Pentatonic Scale

Guitar tab of the D Major Pentatonic Scale

Guitar tab of the E Major Pentatonic Scale

Guitar tab of the F Major Pentatonic Scale

Guitar tab of the G Major Pentatonic Scale

Trouble With Tablature?

If you don’t understand tablature or “tab” for short, don’t worry, it’s very simple to learn! In fact, you might even consider it to be a more simplified version of sheet music, but for the guitar.

First, we have six horizontal lines, each of which represents a different string on the guitar. From the bottom to the top, we have our low E string, followed by the A, D, G, B, and high E strings. On the lines, you will see different numbers which represent the fretted note you are meant to play. So for instance, if you see a “1” on the A string, that means you are meant to play the first fret of the A string. If there is a “4” on the B string, that means you are meant to play the fourth fret of the A string, and so on. However, if you were to see a “0” on the low E string for instance, then that means you are meant to play an open note (a string to be played, but not fretted).

Tablature can be an incredibly convenient means to learn all of your favorite songs or to hash out some ideas. However, that’s not to say that tab doesn’t come with any drawbacks. Musical notation, otherwise known as sheet music, while complex, contains a lot of detail as to how certain elements are to be played. This can be anywhere from the tempo, dynamics, or even the length of certain notes. As for tab, the job mostly falls on you the musician to understand with your own ear how it was meant to be played. However, if you’re fortunate enough, some websites supplying you with tabs have their own means of helping you understand how things are meant to be played. For instance:

H = Hammer-on

P = Pull-off

B = Bend

X = Mute

PM = Palm Mute

\ = Slide Down

/ = Slide Up

~~~ = Vibrato

Another thing to consider is maintaining good playing habits, more specifically, your fingering. When you read tabs or even sheet music, they don’t tell you where your fingers are supposed to go, only what note is to be played. A good habit for a guitarist learning new material is to read ahead of what they’re going to be playing. This helps a guitarist better prepare themselves for what to expect, and what finger they should be starting with. For instance, if you look at a piece of tablature, and you see the highest note is on the 5th fret, and the lowest note is on the 2nd fret, then you will likely want to start with your index finger on the 2nd fret, play the 3rd with your middle finger, the 4th with your ring finger, and the 5th with your pinky finger. Proper finger positioning can make a real difference in your playing technique!

About the Major Pentatonic Scale?

Now that we’ve covered how to play these easy scales, what exactly are they, and how do they function? For starters, our pentatonic scale is different than our traditional diatonic scale in that it has only five notes, while our diatonic scales contain seven. This is why our pentatonic scale is otherwise known as the five-tone scale. A diatonic scale is classified as any heptatonic scale (a generic scale with seven notes) containing five tones, and two half tones. In the case of our major pentatonic scale, however, removes two notes; one from the fourth degree, and another from our seventh degree. In the key of C major, the notes would be C, D, E, G, and A.

There are two kinds of pentatonic scales: hemitonic, and anhemitonic. The former contains semitones within the scale, while the latter does not. Japanese music makes use of both hemitonic and anhemitonic types of pentatonic scales, however, these scales are thought to have even been used back in ancient times, way before the days of Greek Philosopher, Pythagoras.

The pentatonic scale is a relic of the early stages of music’s development, as much of the music found across the world derives from it. The sound of the pentatonic scale gives off a very oriental vibe, sounding very distinct, yet pleasant and peaceful. In fact, if you happen to have a keyboard or piano nearby, you only need to play the black keys ascending or descending to hear this scale in action!

Building a Major Pentatonic Scale

To form a major pentatonic scale, you only need to take whatever major scale you like and play the first, second, third, fifth, and sixth degrees of the scale. For instance, D Major to D Major Pentatonic would look like this: D, E, F#, A, B. Eb Major to Eb Major Pentatonic would look like this: Eb, F, G, Bb, C.

Now, let’s run through how to get you building these on your own! We will first need to define what key we’re playing in. For this example, we will use B Major. Now that we have selected our key, we need to find our key signature. A key signature defines the key and is represented by a collection of sharps or flats at the beginning of a musical composition. Sharps indicate that a note is to be raised by a semitone, and flats indicate that a note is to be lowered by a semitone.

So how do we know what these notes are? We will have to consult the circle of fifths for the answer.

A diagram of the circle of fifths, showcasing all of the most commonly used key signatures.

The circle of fifths is a wheel-shaped diagram that displays the most commonly used keys and their corresponding key signatures. As you can see, the outer ring contains all of our major keys, while the inner ring contains all of our relative minor keys. As you go clockwise around the wheel starting from C major, you will notice that each key signature contains an additional sharp, while as you go counterclockwise, the key signatures gain an additional flat.

Looking at the diagram and what key we’re in, we can see that the key of B major contains five sharps. So how do we determine which notes are sharp? We use a simple acronym: FCGDAEB. This stands for:

“Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle”

Each first letter of this saying represents a different note. The idea is that once you know how many sharps a given key has, using this saying (and maybe your fingers too), you can figure out which notes are sharp! Here are the keys with their collective sharps:

C = No Sharps or Flats

G = F

D = F, C

A = F, C, G

E = F, C, G, D

B = F, C, G, D, A

F# = F, C, G, D, A, E

C# = F, C, G, D, A, E, B

As you can see, C# contains all seven sharps, however, we mentioned earlier that these are all of the most commonly used key signatures. In fact, it can even go beyond C# major into keys that contain double sharps. However, that is some whacky and complex material we won’t delve into for this topic.

Using what we now know about the circle of fifths and B major containing five sharps, let’s use our acronym to figure out what notes these are. Counting to five, we go… “Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And…” so we can deduce that our sharps in the key of B major are F, C, G, D, and A. When we now lay out our B major scale, we get the collection of notes:

B > C# > D# > E > F# > G# > A# > B

Major scales like our B major scale all contain the same pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S). These notes follow this sequence:

T > T > S > T > T > T > S

It’s fairly simple to see this when compared to the C major scale, as it contains no sharps or flats. In the case of our B major scale, however, you can see that the B > C becomes, B > C#, making it a tone apart, just like E > F becoming E > F#. D becoming D# moves closer to E, making it now a semitone apart, as with A becoming A# moving closer to B.

In the case of our pentatonic scales, however, this pattern is slightly different as there are fewer notes to work with. Here is the sequence for a major pentatonic scale:

T > T > m3 > T > m3

While our major pentatonic scale is essentially a more simplistic major scale, the intervals will be slightly different. Between our 3rd and 5th degrees of the scale, we have an m3 (minor 3rd), consisting of a tone and a half. The same occurs with our 6th degree to the 1st (octave). We know this because the 4th and 7th degrees of our major scale were removed to make this a major pentatonic scale. The rest of the notes stay the same.

We just mentioned something interesting, scale degrees. What are they? Each degree 1 – 7 has a unique purpose within a key, as well as its own unique identifier. Using B major as our example once again:

B = Tonic (1st Degree)

C# = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

D# = Mediant (3rd Degree)

E = Subdominant (4th Degree)

F# = Dominant (5th Degree)

G# = Submediant (6th Degree)

A# = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

B = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

Our tonic can be thought of as our home, our tonal center. The supertonic is used interchangeably in some cases with our subdominant (4th degree) as they both share two of the same notes. The mediant is a weak pre-dominant chord often used to expand from the tonic, as they share two of the same notes. Our submediant is one of our more important degrees, a tension builder, sharing one note with our tonic, this typically transitions to our 5th degree. The dominant, next to our tonic is the most important degree where tension has reached its peak. The dominant shares one note with our tonic, however, it’s not the root note of our key like our aforementioned degree contained. Next, we’ve got our submediant. The submediant, our sixth degree shares two notes with our tonic, making it an excellent chord to expand on our tonic. Finally, we have our leading tone, an important degree for our seventh chords, but also a degree withholding a lot of tension, as naturally, it wants to resolve to the tonic. After that, you’re one octave higher from where we began, falling back on the tonic.

Major VS Minor Pentatonic Scale

Now that we’ve covered a lot on our major pentatonic scales, let’s look at the other side of the coin, to our minor pentatonic scales. There are many key differences between these two types of pentatonic scales, but first, we’ll talk about the key.

Going back to our circle of fifths, we briefly touched on our various keys containing sharps. When we’re in a minor key, we begin to focus more on the inner ring than the outer ring. Each of these minor keys is known as a relative key to our major keys in the same column. A relative key differs from a parallel key in that these keys while containing a different tonic, share the same key signature. A parallel key, however, is the opposite, as they share the same tonic, but contain a different key signature. An example of a parallel key would be C major to C minor. A relative key would be C major to A minor.

With this information, let’s use the key of C# minor. In the key of C# minor, we have four sharps, which are F, C, G, and D sharp. We know this by looking at our sequence of sharps added to the keys going around the wheel:

A = No Sharps or Flats

E = F

B = F, C

F# = F, C, G

C# = F, C, G, D

G# = F, C, G, D, A

D# = F, C, G, D, A, E

A# = F, C, G, D, A, E

As per usual, when assigning sharps to the key, we continue to use the acronym: FCGDAEB. This would be different, however, if we were working with a key signature containing flats. To find the sequence of flats added to the keys, going counterclockwise, we would simply reverse our acronym to BEADGCF. This stands for: “Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’, Father”.

Now that we have our key and key signature figured out, let’s get to the C# minor scale. With our key signature included, this scale looks like this:

C# > D# > E > F# > G# > A > B > C#

Much like our major scales, our minor scales also share their own set of tones (T) and semitones (S). Minor scales follow this sequence:

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

When we turn our minor scale to a minor pentatonic scale, we go about it slightly differently than our major pentatonic scale. For the major pentatonic scale, we took away the 4th and 7th degrees of our major scale, however, for our minor pentatonic scale, we take away the 2nd and 6th degrees. Our pattern of tones and semitones then becomes:

m3 > T > T > m3 > T

Playing a scale in a major key to a minor key gives a contrast of feeling between bright and happy, to sad and melancholy. A similar effect applies to their pentatonic forms, where a major pentatonic scale gives a calming pleasant sound the minor pentatonic scale has a bit more of a distinct edge. Both are very nice to listen to and fairly easy to play.

Here is how a C# minor pentatonic scale sounds:

Guitar tab of the C# minor pentatonic scale.

How to Practice With Scales

Practicing with scales is a great way to develop your finger strength, muscle memory, and fretboard knowledge. However, if you want to get the most out of your practice, it’s highly recommended that you practice with a metronome. A metronome can improve your timing and allow you to clean up your playing technique.

There are various inexpensive means of acquiring a metronome, such as smartphone apps, metronome websites on your browser, or even music production software as they typically have one built in. Simply start at a tempo you’re comfortable with, for beginners, it’s recommended to go anywhere from 40 – 60 BPM. As you get more comfortable with the tempo, feel free to bump it up anywhere from 1 – 5 BPM. The important thing is you play slowly at first. If you cannot play it slow, how can you expect to play it quickly? Below are some excellent ways to improve your practice routine with scales:

Up and Down Method

It’s just as it sounds! You play the scale in its entirety through a range of two octaves. Starting on the low E string, and finishing on the high E string. The idea is that once you hit the peak of the scale, you descend back down toward where you’ve started. The catch, however, is that before hitting the note you started on (after completing the scale), you’ll land on the fret right beside it, making that your new starting point. Ascend and descend again, rinse and repeat! A good goal to aim for is to play it without messing up until you hit the 12th fret as your starting point.

It’s up to you, however, to decide what a “mess up” is. If you’re new to guitar, don’t be too hard on yourself! Just focus on finishing the scale.

Pendulum Motion

I like to think of this movement as a “pendulum”, swinging back and forth and gathering more momentum over time. As before, you start on the root of your scale. Following that, you’ll play the 2nd note, then return back to the root. After you play the 2nd, and then the 3rd note, descend back to the root again. Do you see the pattern? The idea is to continue gathering momentum, climbing higher and higher until your finish the scale in its entirety. A good way to envision this is to imagine being at a park and riding the swing set. It starts off small gathering momentum each time around!

Playing In Thirds

Imagine your C major scale laid out before you. You have the notes: C > D > E > F > G > A > B > C. Now if you were to practice playing the C major scale in thirds, you would start on your root note, C, but then skip D, but play E. After, you’d descend to D, skip E, but play F. Descend to E, skip F but play G, and so on. This can be a good exercise to keep your brain sharp and change up your routine if scales are feeling a bit too stale for your liking.

Honorable Mention: Spider Exercises

These aren’t considered to be used in scales, however, they are an excellent means to clean up sloppy playing techniques. The best part about it, is you’re free to change it up as you wish! It involves using each of your four fingers and playing the first four frets in a different sequence as you ascend up the strings. For instance, starting on low E: 1, 2, 3, 4. That means you’d use your index finger, then your middle finger, followed by your ring finger, then your pinky. Then you’d move to the A string: 1, 2, 3, 4. Then your D string: 1, 2, 3, 4. And so on… You get the idea. You’re welcome to change this sequence to any combination. It could be, “2, 1, 3, 4” or, “3, 2, 4, 1”, or even, “4, 3, 2, 1”.

To get the most out of your spider exercises, it’s recommended that you keep your finger glued to the string before having to move it for any other reason.

Conclusion

There you have it! Pentatonic scales are very beginner-friendly, and more importantly, they just sound nice. You could even go as far as to practice with a backing track, and improvise with these scales over them! It’s a great way to learn the fretboard and can be an excellent creative outlet. How will you implement major pentatonic scales into your practice routine? Are there any songs you’re looking to learn with these scales in them? Wherever your endeavors take you, make sure you have fun, and keep on rockin’!