As a beginner, learning to form a barre chord can be a challenging and painful experience for your fingers. With enough practice, however, it gets easier! You’ll come to find that G#m sounds best as one of these barre chords, and offers you a ton of flexibility as these can be formed from multiple positions on the neck. Let’s dive in and learn more about our G#m chord!

Contents

How to Play the G#m Guitar Chord

If you’re a beginner, you may not have learned what a barre chord is. In short, a barre chord, is a chord containing a barre. A barre is formed when you cover a range of strings over a single fret with an individual finger.

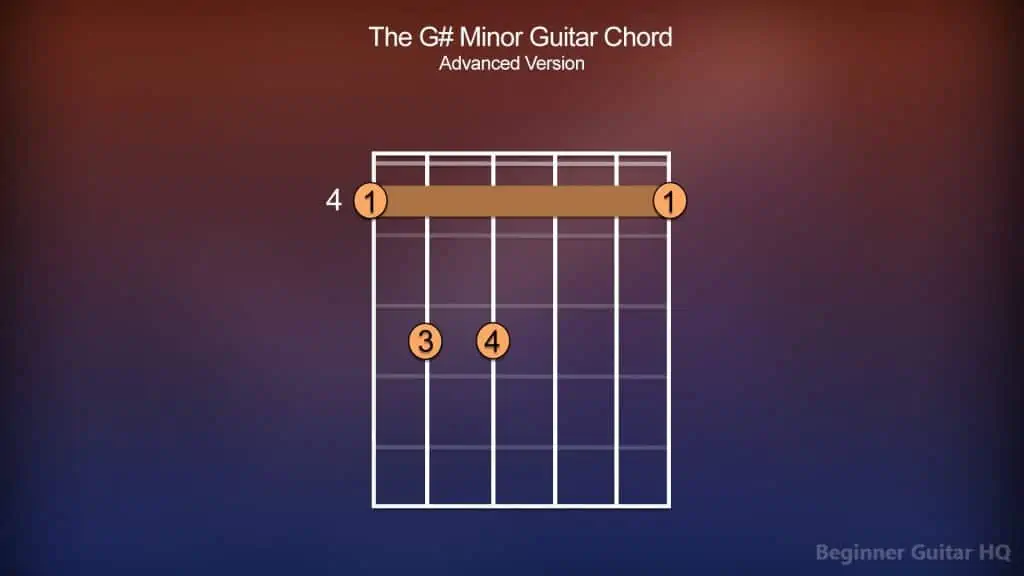

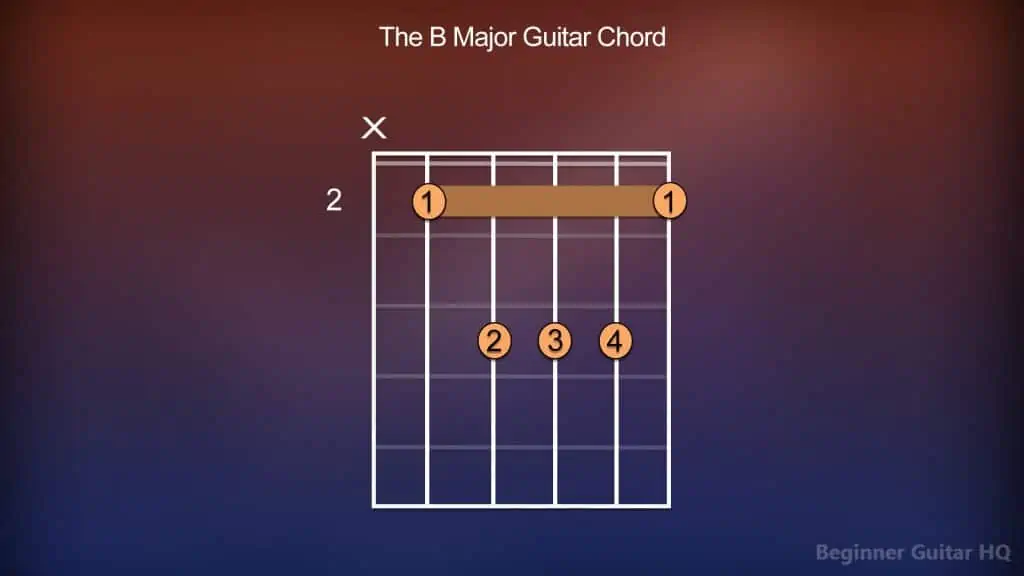

As you can see, in the diagram below, we form a barre to complete our bar chord:

A chord diagram of the G# minor guitar chord, in its standardized form.

As you can see on the digram there are a bunch of circles with numbers within them. The numbers range from 1 – 4. These numbers are to help you map out what frets you are supposed to play with your four fingers. The number 1 is for the index, 2 is your middle finger, 3 is your ring finger, and 4 is your pinky finger. You will see a long bar stretching from 1 – 1 across a series of strings; this is where we form our barre. Next to that, you’ll see a number 4 off on the left of the chart, and this implies that we play our barre on the 4th fret.

How to properly play the G#m chord, you’ll first take your index finger and lay it down vertically across the strings, from the low E string to our high E string on the 4th fret. You just formed a barre! From there, you need to stretch your ring and pinky fingers out to the sixth fret. Your ring finger goes on the A string, and your pinky right below it on the D string. Congratulations, you have formed your barre chord!

Give it a strum and hear how is sounds. If it doesn’t sound very good, perhaps your strings sound muted, or there is a lot of buzzing, you just need to be patient. This is likely because you haven’t built up enough finger strength yet and that you’re also not coming directly down on the frets. Practicing chords consistently can help you improve this, as well as different finger dexterity exercises to get more out of your ring and pinky fingers.

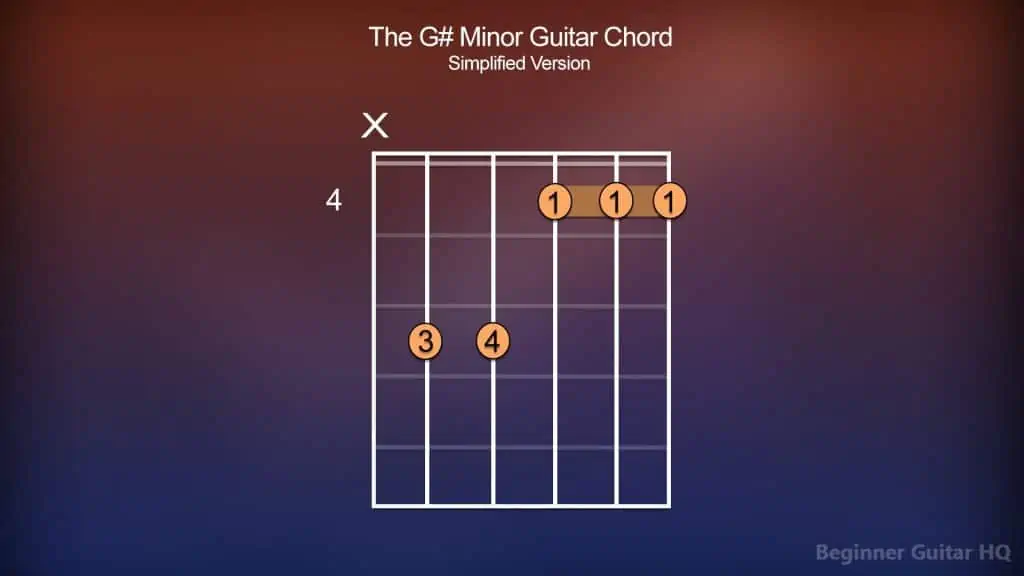

If that is too challenging for you, don’t get discouraged, over time as you practice, you will get more comfortable with it. Some good news, however, is there is a slightly more simplified version you may choose to practice with until you can perform the whole barre:

A chord diagram of the G# minor guitar chord, but in a simplified form for beginners.

You’ll notice that over the low E string, there is a large X. The X implies that this string is not to be played. Much like the last diagram, the index finger is draped over the G, B and high E strings on the 4th fret. The ring and pinky finger go to their original homes too, on the 6th fret.

Give it a nice strum. You might notice it sounds a lot better! Perhaps, less buzzing, and muted notes. This is a good place to start until you can get used to forming the whole bar. Once you get comfortable with this version, give the more advanced version another shot!

The Composition of Chords

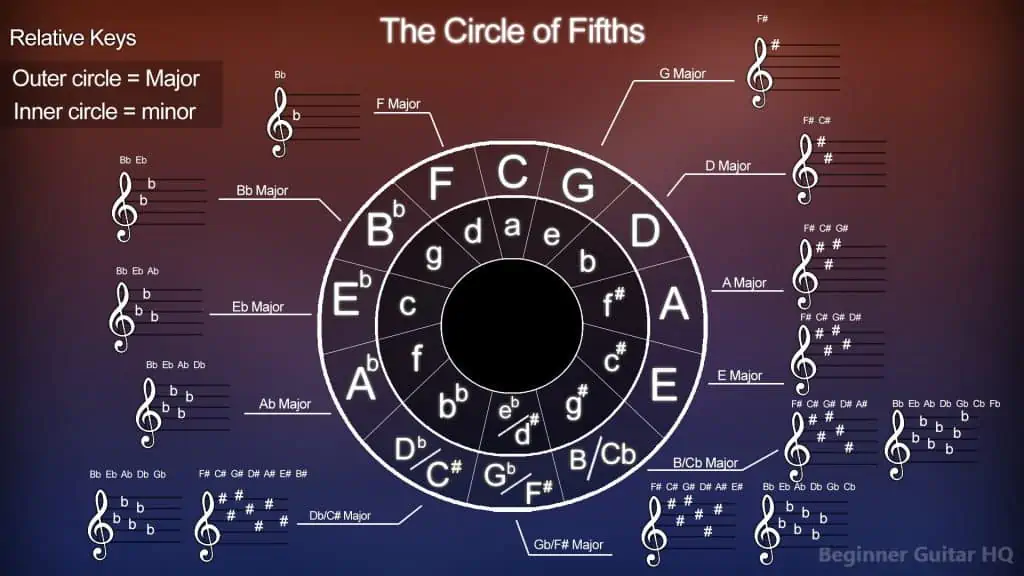

Now that we know how to form our chord, it’s helpful that we know why it works. In fact, learning why it works can help you understand a little more about chord progressions, something we will go over later on. First, let’s take a look at the Circle of Fifths and see what is in the key of G# minor.

The Circle of Fifths

This is a handy tool for figuring out the different key signatures of various keys. In the key of G# minor, we have five sharps, which are F, C, G, A and D. When a key is sharp (#), that implies that it is to be raised by a semitone. On the contrary, if it were flat (b), it would be implied that you would lower the note by a semitone.

A diagram of the circle of fifths, showing the key, and relative Major or G# minor.

The Minor Scale

The major and minor scales have their own patterns to follow, which operate in the form of tones (T) and semitones (S). You may also consider these two types of scales to be “diatonic scales”, meaning that within every octave, there are five tones, and two semitones. Since we are learning about a minor chord, the pattern within a minor scale would look something like this:

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

Which within our scale of G# minor, would look like this:

G# > A# > B > C# > D# > E > F# > G#

Now, remember, within the key of G# minor there are five sharps: F, C, G, D, and A. If we look at the standard pattern of a minor scale, with our tones and semitones, you will find that our key signature also obeys the confines of this pattern. Let’s take a look:

- G# > A = (T)

- A# > B = (S)

- B > C# = (T)

- C# > D# = (T)

- D# > E = (S)

- E > F# = (T)

- F# > G# = (T)

Our B and C notes are typically a semitone apart, as are our E and F notes, however, C# and F# make them a tone apart. On the other hand, the A gets a sharp, bringing it closer to the B as does D to E.

Here’s an interesting way of looking at it. If we look at the pattern in our major scale, and shift it two spots to the right, we would get the minor scale. Pretty neat, huh?

Major: T > T > S > T > T > T > S

Minor: T > S > T > T > S > T > T

Triads

Triads are the backbone of our basic major and minor chords, however, it’s important to know that all triads are chords, but not all chords are triads. 7th chords are but one example of this, as they may contain a triad, but also have a 7th interval, which may be major, minor or diminished depending on the chord.

Triads are formed on the basis of our 1st, 3rd and 5th degrees of our scale. These are otherwise known as our tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees of the scale. In a minor scale, these intervals would be:

- Minor 3rd (our 1st to our 3rd degree of the scale)

- Major 3rd (our 3rd degree to our 5th degree of our scale)

- Perfect 5th (our 1st to our 5th degree of the scale)

Therefore, in our G# minor chord, we have the triad of G#, B, and D#. These are the notes that you would use to produce a G# minor chord.

How the Circle of Fifths Works

We had briefly touched on the circle of fifths earlier, however, it’s important to understand how this works, so that you can not only use it effectively, but remember it without the chart!

Along the outer ring of the chart, we have our major keys. You’ll find that the right half of the ring contains sharps (#) and the left half contains flats (b) in their key signatures. Within the outer ring, there is another ring containing relative minors. You could even consider the outer ring to be relative majors to the inner ring. What this implies, is that the relative keys share a key signature. For instance, D major would share a key signature with B minor. E major shares a key signature with C# minor. Ab major shares a key signature with F minor. And so on!

C is the designated starting point for the major keys, and A is the starting point for the minor keys. These keys can be everything or nothing. For instance, if I was to throw a sharp on C major, making it C# major, it would get all seven sharps. The same would happen if I gave it a flat, making it Cb major, thus giving it seven flats in it’s key signature. C major on its own, however, contains no sharps or flats. A minor is treated this way as well.

So how do we know which notes are sharp or flat in the key signatures?

It really depends on what key signature you are trying to figure out. If you are trying to find the sharps of a key, there’s an old acronym to help you figure this out: Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle. In each word, the first letter pertains to what note will be sharp in sequential order. Let’s use the minor keys for this example:

A minor = Nothing

E minor = F

B minor = F, C

F# minor = F, C, G

C# minor = F, C, G, D

G# minor = F, C, G, D, A

D# minor = F, C, G, D, A, E

A# minor = F, C, G, D, A, E, B

As you can see above, B minor will contain two sharps, F, C. D# minor will contain six sharps, F, C, G, D, A, E. Our G# minor will contain five sharps, F, C, G, D, A. It can be helpful to count with your fingers while using this acronym to figure out the appropriate sharps.

On the other hand, let’s say we wanted to figure out our key signatures containing flats. We would simply reverse the acronym we used before: Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles’ Father. Which would look something like this:

A minor = Nothing

D minor = B

G minor = B, E

C minor = B, E, A

F minor = B, E, A, D

Bb minor = B, E, A, D, G

Eb minor = B, E, A, D, G, C

Ab minor = B, E, A, D, G, C, F

It’s relatively simple to remember the circle of fifths as you only need to remember half of it to figure out the other half. If we remember our magic number “7”, then it gets much easier. For instance, if you know that C# minor has 4 sharps, then guess how many C minor will have? The answer is 3. If we take 4 and add 3, it will equal 7. Then you can count with your fingers and say, “Battle Ends And..”, therefore in the key of C minor, we have 3 flats, which are B, E and A. Pretty simple, huh?

The circle of fifths can improve your music theory and allow you to see the relationships between keys. It’s easy to learn, and will help you for years to come.

G# Major to G# Minor

The relationship between two notes that share the same tonic, like G# major to G# minor for instance, are what we call parallel keys. So, what’s the difference between them? Unlike our relative keys, parallel keys do not share the same key signature. G# minor contains five sharps, which are F, C, G, D, A. G# major on the other hand contains six sharps, and one double sharp. F gets the double sharp, and the rest of the notes are regular sharps: C, G, D, A, E, B.

Important note

You might have looked for G# major on the circle of fifths, however, you won’t find it there. The circle of fifths contains the more common keys, as this one is a little more complex. You can almost think of it as taking an extra lap, going past C# containing seven sharps, as what’s left to do, landing on G# but give an already sharp note another sharp. This would continue to happen if you were using D# major, and A# major. This is where things get kind of whacky.

Back to distinguishing our major from our minor counterpart, the major scale follows it’s own pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) which we had gone over earlier:

T > T > S > T > T > T > S

Therefore, our scale would appear as:

G# > A# > B# > C# > D# > E# > F# # > G#

Our F note would be raised two semitones, thus making it a semitone away from G#, and a tone away from E#. It always falls in line to our pattern, dependent on whether we’re in a major or minor key.

Knowing our scale, let’s build our major triad, using the first (tonic), third (mediant), and fifth (dominant) degrees of our scale. We would get the triad of G#, B#, D#.

The intervals of the notes within the triad differ from that of a minor triad:

- G# > B# (Major 3rd) Whereas a minor triad would have a minor 3rd.

- B# > D# (Minor 3rd) In a minor key, this would be a major 3rd.

- G# > D# (Perfect 5th) Which is no different from a minor triad.

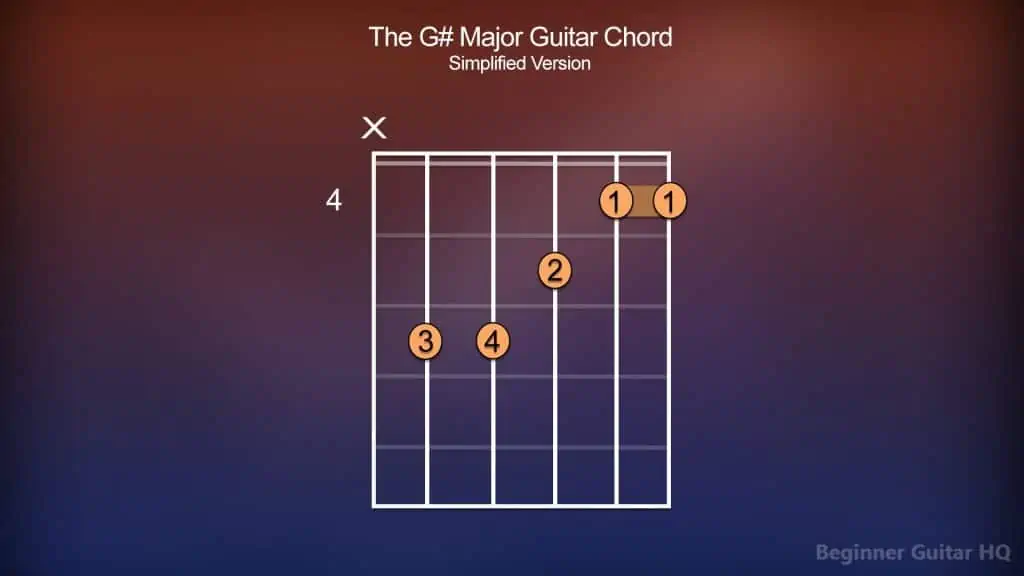

The chord would look something like this on guitar:

Chord diagram of the G# Major barre chord in its standardized form.

As before, if you want to form this chord you will need to drape your index finger vertically across the 4th fret, from the high E to the low E string. The middle finger will go on the G string on the 5th fret, and the ring and pinky finger will go on the 6th fret’s A and D strings.

However, if you struggle with barre chords, and would like to feel and hear the difference, there is a simplified version below that you can play:

Chord diagram of the G# Major guitar chord in its simplified form for beginners.

As before, the low E string is not to be played, and the high E and B strings are held down by the index finger on the 4th fret. The middle finger goes on the 5th fret, G string. The ring and pinky finger go on the 6th fret, A and D strings.

Play the G# Major chord, then play the G# minor chord. The real difference that you’ll notice is the B in its minor form transitioning to C in its major form. A G# minor triad contains the notes, G#, B and D#. A G# major triad will have the notes G#, B# and D#, and this makes sense, because when the B note gains a sharp is becomes B#/C. The rest of the notes within both chords will remain the same.

G# Minor’s Relative Chord

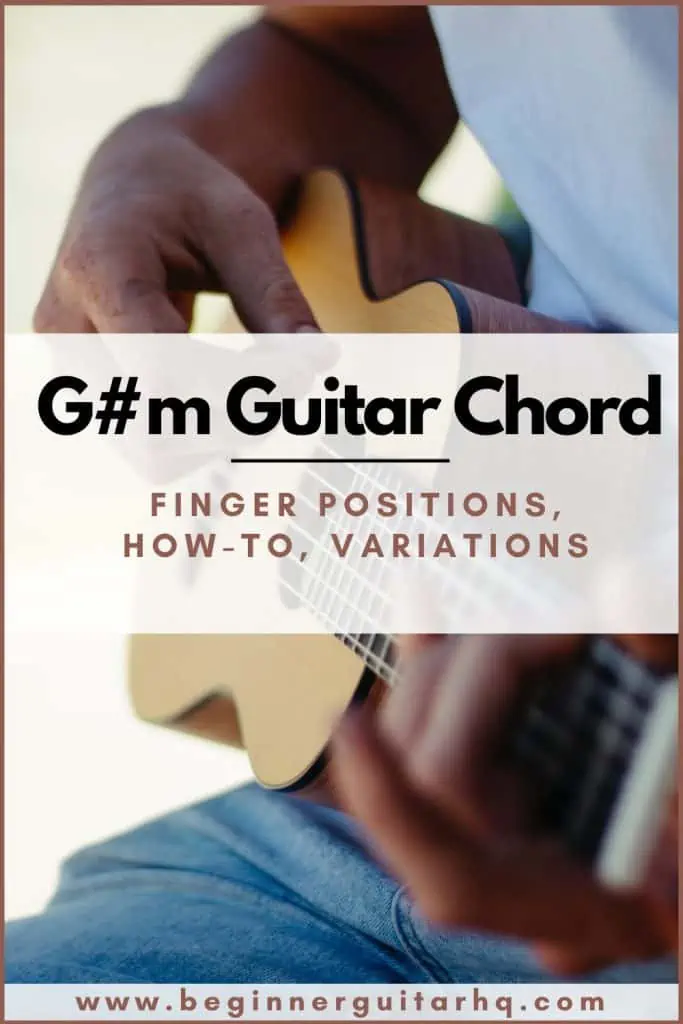

If we wanted to play the relative major to G# minor, then we would have B major. This, like our G# minor key, will also contain five sharps: F, C, G, D, A.

You’ll find that G# major shares similarities with its relative minor, but follows the rules of a major scale. The B major scale would look like this:

B > C# > D# > E > F# > G# > A# > B

Giving us our triad of B, D#, and F#. The chord would look something like this:

A chord diagram showing the makeup of the B Major guitar chord.

Figuring Out Chords that Go Well Together

Believe it or not, there is a method of finding chords that go well together! This can make it much easier for you to make chord progressions that transition smoothly.

The reason why most known chord progressions sound great is because they fall within the same key. Let’s have a look at our G# minor triads:

- 1st degree = G# minor – G#, B, D#

- 2nd degree = A# diminished – A#, C#, E

- 3rd degree = B major – B, D#, F#

- 4th degree = C# minor – C#, E, G#

- 5th degree = D# minor – D#, F#, A#

- 6th degree = E major – E, G#, B

- 7th degree = F# major – F#, A#, C#

These are chords that are available to you, falling within the key of G# minor. The best part is you’re free to mix and match and find a progression that you like!

A fairly common progression is the (1st, 4th, and 5th) which would be (G#m, C#m and D#m). The reason why this works is that we have our tonic, G#m, and moving to the 4th degree C#m to build a light tension, and having it continue to build upon the 5th degree, D#m, before returning home to our tonic, creating a sense of resolve.

Another good progression for G# minor is the (1st, 6th and 7th) making the chords (G#m, E, and F#). Yet again, we have it where we start at our tonic, the first degree, G# minor, before moving to our sixth degree, the submediant, E Major. You can think of the submediant as a chord that doesn’t hold a lot of tension, but works as a good bridging point between the Tonic, to a chord building more tension. This leads us to our seventh degree, the leading tone, F# Major. After the leading tone, we’re brought back home to our tonic, G#m, bringing a sense of resolve.

This can be done for just about any chord you choose to make your tonic, even if you would prefer to start on another degree of the scale. It might take some time to lay out every triad within the key, but it’s worth the effort to get a chord progression that you enjoy, and that fits the mood and overall story the song is trying to tell.

Conclusion

The G# minor chord is a very beautiful sounding chord, and it can really shake things up if you decide to add a 7th to it, giving it a bit more character. However, now that you know how it works, how will you use it? What chord progressions will you make?