At BeginnerGuitarHQ, it’s our mission to teach you how to play the guitar as well as possible. One of the most important parts of a guitarists toolbox is the humble scale. You’ve probably become rather used to standard major and minor scales, but were you aware of the basically endless possibilities modes afford you? They can change the tone, style and feel of your playing with just one unexpected note.

In this important guide, I’ll be explaining how you can use the Phrygian mode within your guitar playing.

If you’re on the lookout for a way to spice up your melodies, chords and improvisation look no further than this useful guide.

First Things First

What Is A Mode?

The most important first thing to be aware of when approaching the Phrygian mode, is what a mode actually is. Technically, the term ‘key’ only applies to diatonic music. As such, you can have your major and minor keys and be diatonic to them (that is, stay within them when playing), but you can’t really use the term diatonic to refer to a mode. A mode is, to all intents and purposes, however, basically the same as a key. You’d very rarely see the notes of the mode written out in a key signature, but they’re basically the same thing, just with more possibilities.

There Are A Lot Of Modes

Today, we’re looking at the Phrygian mode (which we’ll get to in a moment) but there are hundreds more modes in existence. One way to look at modes is to imagine a piano. The white notes from C-C make a simple C major scale. Move up to D, and if you simply go from D-D without hitting a black note, you’ll be playing the Dorian mode. The same with E, F, G, A and B. Now remember that there is a minor scale equivalent (so the equivalent of having the same approach, but with the C minor scale as your basis), and a harmonic minor scale equivalent, and melodic minor, and all of the modes, and all of their variants. It basically goes on forever, but you don’t need to worry about that. For now, you just need to worry about the Phrygian mode.

And What Is The Phrygian Mode?

The Phrygian mode is, in its purest form, the white notes from E-E. This means that an E Phrygian scale is E, F, G, A, B, C, D. Obviously, this is the enharmonic equivalent of C major, so the notes are exactly the same; it’s the way you use the scale that changes things.

The most important notes in the E Phrygian scale are:

- E. The tonic/root note. You’ll know if you’re in E Phrygian if you only play white notes but the music sounds ‘final’ when you land on an E.

- F. This is the semitone opening which gives the scale its very strange, distinctive sound (which many say sound ‘Egyptian’.)

- G. This note gives the scale its minor implication. As you have the minor 3rd of the minor scale, this means the tonic chord is E minor.

- D. This is the 7th. This furthers the idea that this is a very minor scale in quality, as it doesn’t have the raised 7th.

So remember: E, F, G, A, B, C, D.

E Phrygian Mode

Transposing The Phrygian Mode

Moving The Phrygian Mode To C

While looking at the Phrygian mode in its most simple formulation gives us the simplicity of the E, F, G, A, B, C, D, scale mentioned above, it isn’t as though the Phrygian mode can’t be moved to every single other note.

We can start with the C Phrygian mode, which brings the E Phrygian down by a minor third. This means the C Phrygian is made up of the notes C, Db, Eb, F, G, Ab, Bb. The tonic is C, and that all important opening semitone comes on the Db. We’ll now focus the rest of this guide around the C Phrygian mode for simplicity, but remember that it can be moved to any note you need via transposition.

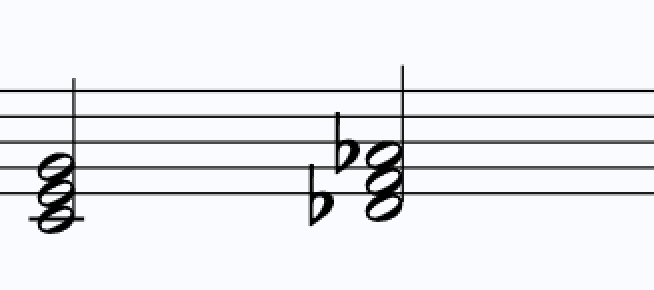

C Phrygian Mode

Moving The Phrygian Mode To Every Other Note

The easiest (but longest) way to do this is to simply look at the notes, and move every single one of them up by the amount necessary to reach the new tonic. For example, if you’re starting on C and want to play the Eb Phrygian, then you need to move every note up by a minor 3rd. Take the Db and move to an Fb, the Eb to a Gb, the G to a Bb. Keep going until you’re in the new correct place.

The second way, which is quicker but a little more complex, is the preferred method which will benefit your theoretical understanding of the mode as well as your use of it. You’ll need to remember the interval pattern of the Phrygian mode:

Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone

Now you can use this anywhere you want. To create the A Phrygian scale, for example, start with that movement of a semitone that takes you from A to Bb. Then move by four full tones through the notes C, D and E. You can then move by a semitone once again to reach the F, before jumping by another two tones: G and A. That’s it.

Apply this same logic to any note you may need to use, and you have a basic understanding of how to form the Phrygian mode anywhere you want, and can start to use it in melodies.

Using The Phrygian Mode In Melody

The Phrygian mode gives you a lot of melodic freedom. Most of the scale is simply built from a minor scale that you’re probably very much used to using anyway, but every now and again, you can sneak in that incredibly distinctive minor 2nd interval and remind your audience that this isn’t your everyday minor scale. We’ve put together a list of things to do (if they sound good) when playing melodies in the Phrygian mode, and a few things you probably want to avoid.

Avoid: Making The b2 Sound Accidental

You’re probably familiar with that famous quote about wrong notes: “There are no wrong notes. It’s what you play after that determines if the note is right or wrong”. In a way, a genius guitarist could hit a wrong note and work his way around it to make it sound right in context. That much is true. However, no matter how much you’re able to rectify a slip up after you’ve made it, it isn’t always going to work. Unless you’re performing the most avant-garde, atonal piece of free jazz in the world, then at some point, your ‘wrong’ note will remain exactly that.

In the Phrygian mode, this is even more likely to crop into your playing as the minor 2nd right at the start is such an unexpected interval. You might feel like you’re still in the Phrygian mode, but a sudden jump from Eb to Db might not sound right, no matter what the context. If you can’t picture how it’ll sound in effect, then you might want to avoid risking it.

If you do end up hitting that b2 and making it sound like an accidental wrong note, then there are a few things you can do. If you’re quick enough to realise it as soon as you land on it, then all you’ll need to do is slide down to the tonic. If you play a Db and it doesn’t sound right, then simply slide down by a semitone and the likelihood is the tonic (as long as you haven’t modulated) will sound alright. Alternatively, if you can’t get away quick enough, then a bend up to the major 2nd instead will probably fix the issue. This is very much context dependent and might not end up helping you out at all, but more often than not, one of those fixes will help you out.

Do: Emphasise The b2 (If It Sounds Right)

Each mode has its own distinctive tone and sound, and that is almost always caused by the unique intervals that separate it from a standard major or minor scale. In the case of the Phrygian mode, this is the b2. If you play your tonic, then skip up to the minor 3rd, then 4th and 5th etc., then you can say you’re playing the Phrygian all you want, but you aren’t. The note that gives this mode its flavour is the minor 2nd.

I’m not saying that you should go out of your way to include a minor 2nd interval if it sounds wrong, but if you want to establish the tone of the Phrygian mode specifically, then this is what you should be doing. Moving from the tonic up to the b2 is a sure-fire way to make it very clear what sort of tone you’re aiming for. Similarly, descending from the dominant note down to the b2 creates a jarring tritone interval that could have particular power when you’re trying to give off the dark, creepy vibe that often goes hand in hand with the Phrygian mode.

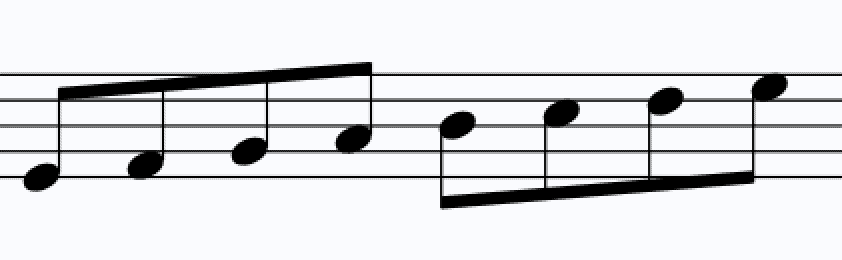

Emphasising the bII in melody

Do: Use That Whole Tone Run

The second most important part of the Phrygian’s distinctive sound is the whole tone run of four notes that the b2 creates. By flattening the second note in the scale a run of notes (which in C Phrygian would be Db-Eb-F-G), you get the first four notes of a whole tone scale. We’ve looked at the creation of whole tone runs in modes in our guide to the use of the Lydian mode, but its appearance here is arguably even more interesting.

Firstly, its sound is one of the most recognisable in music. The whole tone sound gives off a natural, unresolving dissonance/consonance which often appears in film scores to represent dreams. In your use of the Phrygian mode, it’s likely that you’re going to be going for darkness, and the airy sound of this whole tone run complements that perfectly. The even more unique thing about the presence of this whole tone run here is that, in its descending form, it effectively does resolve onto the tonic by a semitone. Coming down from the G, F, Eb, Db is not only a unique, jazzy and interesting sound, but it feels very final when reaching the C afterward.

Using the whole tone run in melody

Do: Play On The Mode’s Darkness

Speaking of the ‘purpose’ of this mode, it is one of the darkest modes on offer, and as such, you should be getting its full dark potential. It takes the already dark minor scale and adds an extra flat at a vital point, so using this mode to create a bouncy, uplifting track is always going to be difficult. If you can (and want to) then go for it, but I’d say that you should be trying to make the most of its dark sound.

The easiest way to do this is embrace its chromaticism. As mentioned, your move from II to V is a tritone, which isn’t normally present in the scale. As such, you can use this to create a distinctly jarring melodic contour, which can be strengthened by using the semitone between the tonic and the b2 as well.

You can also, of course, put the scale directly against its accompaniment. If you’ve got a relatively consonant accompaniment, then using the tritone intervals and semitones to your advantage will give a dissonant sound (especially if you place the b2 above a tonic chord), though maybe that is left for the upcoming section on harmony…

Do: Try Using It In Improvisation

The Phrygian mode might seem like a complex theoretical and compositional tool, but it doesn’t always have to be. Once you realise that the standard Phrygian mode is simply a minor scale with the second note flattened, you can work it into your soloing and improvisation with ease.

Of course, the scale lends itself well to metal and hip-hop music, but it doesn’t have to be limited to that by any means. You could start off by working your way to full use: in a bluesy rock track, you might ‘borrow’ the distinctive b2 as a passing note, rather than a full and frequent part of your melody. This means you’d play it and quickly resolve either up or down to a different note. After you’re used to using it in this context, you might want to promote yourself to using it as a longer, held suspended note, and then you might feel comfortable to work it into your melodies fully.

Avoid: Remaining Phrygian For No Reason

One of the key things to remember when using modes is that no one is forcing you to. There is no reason you absolutely must stay in the Phrygian mode if it doesn’t sound right, or it isn’t where you want your music to go. If you’re improvising over a chord sequence that uses the Phrygian mode throughout but you think a D natural would sound better in place of a Db at one point in the melody, then you don’t need to play the Db.

The Phrygian mode is there to give your music effect and you can draw on it when you’re looking for a distinctive sound because a lot of the time, it’ll be able to enhance what you’re trying to play. Just remember that this isn’t always going to be the case.

Using The Phrygian Mode In Harmony

Once you’ve figured out how to make the most of the Phrygian mode in your melodies, you can start working it into your harmonic patterns. Chances are that if you’ve been using it melodically, then you’ve already been playing over some very distinctive sounding Phrygian chord sequences. Here are a couple of things to avoid harmonically, and a few elements that might enhance your use of the mode.

Avoid: Accidental Modulation

This is an issue that can have an impact on all modes. As we saw at the start of this guide, the Phrygian mode on E is simply the white notes on a piano from E to E. Any piano player will be aware that these are the same notes as the C major (and A natural minor) scale. This shows the importance of the order in which and the way in which you play certain pieces and, in particular, the way you construct chord sequences.

If you’re playing in the C Phrygian, the notes you are dealing with are the exact same notes as those found in the standard F minor scale, so you’ll need to be careful not to accidentally modulate to this key. If you play the C minor chord, this is the tonic of your Phrygian mode scale. However, it doubles as the dominant of F minor. As such, it might end up sounding more natural for you to continue down to the F minor chord and resolve there, which could really throw off other members of your band in a live setting.

Do: Use Chord bII (and bIImaj7)

Much like my above suggestion that you use the b2 in melodies to make it clear what mode you’re using, the same can be said in harmonic sequences. The most distinctive chord in the mode is the bII. Moving from chord I straight up by a semitone to the bII is probably clearest way to confirm your use of the mode to the listener.

In a slightly more jazzy setting (which is as good a way to use the mode as a dramatic film score), you can use the bIImaj7b chord to the same effect. If looking for a slightly more advanced use of harmony, then you can use this chord as part of a Neapolitan cadence in place of the dominant chord, but that’s a story for another day.

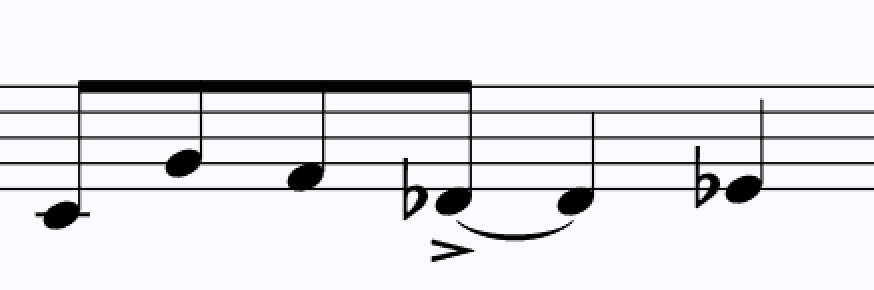

Using chord bII in harmony

Do: Borrow Phrygian Chords

One of, if not the, best things about the use of modes is the ability to borrow from them. This does pretty much exactly what it says on the tin. Borrowing from a mode is simply the act of taking a chord that would be a prominent part of a different mode and temporarily using it within a chord sequence that isn’t in the same mode.

With the Phrygian mode, for example, the most interesting chord you can borrow is the bII we discussed above. A smooth movement from a Cmaj7 (a key chord in C major that doesn’t at all fit in C Phrygian) up to a Dbmaj7 is a classic sound in jazz which doesn’t mean you’ve modulated or changed tonal centre; you’ve just ‘borrowed’ from the Phrygian mode.

Do: Employ New Dissonances

That one change of note opens your music up to a whole new realm of potential chromaticism and dissonance in your harmonic writing. Staring you in the face is the obvious chord we’ve been mentioning throughout this guide: Dbmaj7. However, it is the way that Db can be used elsewhere that is more interesting.

For example, this mode doesn’t have a standard dominant chord. The chord V will always (as long as you stick to the mode) be diminished thanks to the Db. Furthermore, if you’re a fan of 9th chords, then try using one on the C minor tonic. It won’t be a standard dominant 9th, but a very interesting (and, in a certain way, very dissonant) Cm9 chord. This is a chord with a huge versatility in the world of jazz.

Do: Raise The Seventh If You Need To

Now, taking this piece of advice will take you away from the standard Phrygian mode if you take it on board. However, remember what was said above about not forcing yourself to stay Phrygian if you don’t need to.

One of the issues with the Phrygian mode is the way the seventh in the mode is still a Bb (if you’re in C; also called a Mixolydian seventh) which makes it hard to confirm the tonic in certain contexts. If you want to make it very clear that you’re trying to resolve to the C, while still keeping the Db as an important part of your mode, then feel free to raise the seventh. This will turn the Bb into a B, and work as a leading note that will lead directly into the tonic. Then you can resolve to the C minor with clarity, even when your Db is still present. This is because the note both above and below the tonic needs to resolve to the tonic.

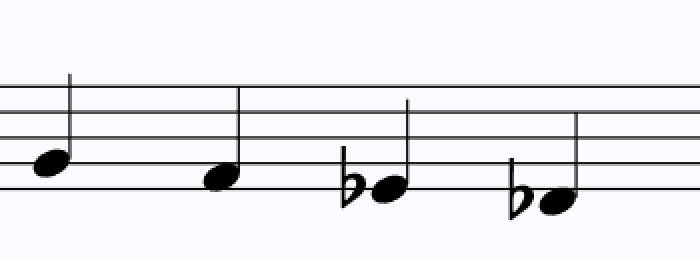

Raising the seventh if needed

Avoid: Accidental Semitone Clashes

While both of my last two points have encouraged the use of semitone movement in your Phrygian harmony, you still want to be careful. That interval is arguably the most dissonant available in music, and if you start chucking a semitone clash into every chord you use, things might start taking a strange turn…

When placed carefully, a semitone can work wonders for your harmony, but just make sure to test out certain sequences before risking them in a live setting.

Examples Of The Phrygian Mode In Use

- Prologue (From The Lord Of The Rings) – Howard Shore. The first piece of music you hear in The Lord Of The Rings actually uses the Phrygian mode. Obviously, as this prologue hints towards some of the most important themes from throughout the franchise, it doesn’t stay exclusively in the mode. However, it is still important. The reason it works so well with the visuals on the screen at this point is due to its minor tendencies being darkened even further by the presence of that minor 2nd right at the start.

- Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun – Pink Floyd. The early work of Pink Floyd was driven forward by the strange compositions of Syd Barrett. This track, taken from their second album, is the only song in the band’s history to feature both Barrett and his replacement, David Gilmour. It is interesting to note, then, that the only time they shared a track, it was to play in a strange mode. The track begins with a very distinct riff that utilises that minor 2nd leap straight away in an E Phrygian setting, before hints towards a 12-bar blues organisation means we move up to the A Phrygian soon after.

- Tool – Reflection. The Phrygian mode (or, at least, movement of a minor 2nd) is one of the most distinctive features of Tool’s dark sound. ‘Reflection’ shows this off in the clearest way, with its opening moments using the B Phrygian mode. This means that the semitone movement is very simply between a B and a C. Also, thanks to the band’s extended and experimental songwriting style, the track also lets us hear the Phrygian mode in passages we can assume are probably improvised.

Different Types Of The Phrygian Mode

- Phrygian Dominant. The closest relative to the standard Phrygian mode is the Phrygian Dominant. In fact, it is the same scale, but with a major third instead of a minor third. This might sound like small change, but it has a huge impact on the sound. Firstly, it creates an augmented second between the minor 2nd and major 3rd of the scale. This intervals is associated with the harmonic minor, so hearing it out of place head is very distinctive. Furthermore, the gap between the 3rd and the 4th is now just a semitone, which the same as the gap between the first two notes. Both of these changes give the scale a decidedly ‘evil’ and suspicious sound when played. It works wonders for film music, but is rather hard to tame for pop. Finally, it means your tonic chord is major. While the Phrygian is very typically minor in tone and use, this major chord can really make your listener’s expectations change course pretty dramatically.

- Double Harmonic Major. The Double Harmonic Major mode is centred on a similar premise to that of the Phrygian Dominant. The only difference is that, alongside the major 3rd, we also have a raised seventh. This means that, just like the harmonic minor scale, we have an augmented 2nd leap right at the end; interestingly, we also have one earlier on between the minor 2nd and major 3rd. Having two of these very unique sounding jumps within the same scale gives it a very distinctive sound. Not only can your tonic chord be major, but your dominant chord can too. This can really start to mess with the perception of darkness created by that minor 2nd interval.

- The Flamenco Mode. Technically, this isn’t a mode in the traditional sense. The Flamenco mode isn’t a set of specific pitches that create a scale, and more a selection of chords so named for their huge prominence in Flamenco music. At their core, the root notes of each chord used follows the same pattern as the typical Phrygian mode, being defined by that opening semitone. However, you’ll want to harmonise the first chord with an unexpected major third, and the third chord, with the most expected minor version of the previously major note. Try playing a standard E major chord on guitar, then move the shape up by a semitone, and then again by a whole tone. That’s about as a standard a Flamenco pattern as one can create.

Conclusion

The Phrygian mode is one of the most recognizable and distinctive modes in music. It has the ability to work wonders in a dramatic, tension-filled and scary film score just as easily as it can work in a jazzy piece of improvisation.

The main things to look out for are the use of the minor 2nd interval in both melody and harmony, while remembering that you can freely borrow from the Phrygian mode even if you aren’t using it exclusively, while also remembering that you don’t have to stick to it relentlessly if it isn’t creating the sound you’re aiming for.