Transposing chords is a necessary skill to accommodate a singer’s vocal range. Especially on the fly. We can’t always get the music printed in a different key and it’s not always appropriate to use your phone, tablet, or laptop. So while it’s all good to use the transpose buttons on Ultimate Guitar or one of the other tab websites, it’s not always practical.

Once you get the hang of it and can use easy methods of changing the key or just work it out quickly in your head, you’re set up for doing it on the fly as needed. Even if you’re working off memory instead of having the music in front of you.

I’ve had to do this a few times, without a capo, and when my mind is sharp and fresh, or the pressure just forces laser focus and lightning quick thinking, it works out well enough.

But it’s for those times when you’ve been working or studying, have a lot on your mind, or didn’t get the best night’s sleep (hopefully because you had a lot of fun… I hear you if not), that you want to know the quick and easy tips too.

So here you go.

Use a Capo

This is one of the quickest and easiest ways to change the key. You won’t need to play different chords. The capo acts as a new bridge, so you keep playing those same chords, but you’ve transposed the key up however many frets higher you’ve put your capo.

Using a capo is easy. Depending on the type you have, you just clamp it around the neck of the guitar, with the straighter side across the strings. If you want to play in A for example, but you only have the chords in G, you just put the capo in the second fret and play the chords for G as per usual beneath the capo.

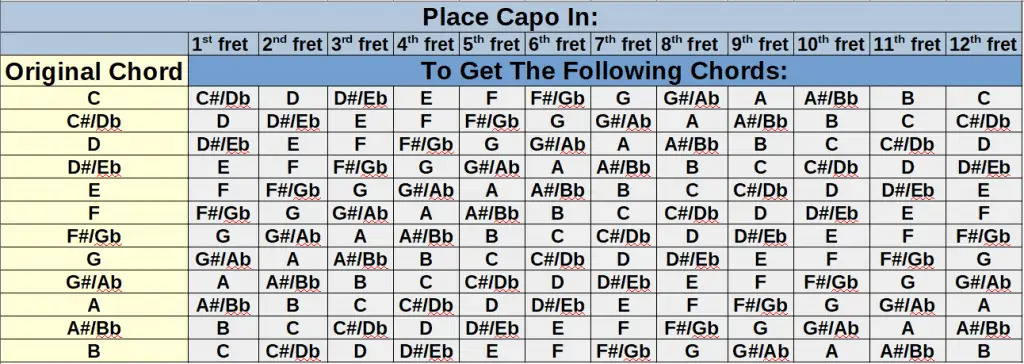

Here’s a chord chart to quickly see where you need to place your capo:

If you need to get a guitar capo, have a look at these suggestions.

Sometimes though, using a capo isn’t going to work. You can see for example that if you’re in C, but you want to play in B, you’re going to have to place it in the 11th fret. If you have a cutaway guitar, that might not be as much of a big deal.

But a guitar that isn’t a cutaway shape makes it difficult to play things above the 12th fret. It will also be very high-pitched at this point.

Don’t get me wrong, higher voicings of chords, especially if someone else is playing the lower voicings, sounds nice in some genres. But I personally don’t enjoy extremely high-pitched chords for strumming. It’s a different story if you’re playing lead or picking, but for strumming, it’s just not my thing.

So employing the below methods will help you out in this regard.

Count How Much You Need to Go Up or Down

This one is pretty self-explanatory, but the implementation can be a bit weird if you aren’t quite sure of the chords within the key.

Moveable Chords

If you’re playing only in moveable chords, like barre chords or jazz chords, that’s pretty easy as long as you know where your root note is. Taking the example of G again, let’s say you want to play in A.

Move your root note, so in the E-shape barre chord, the 3rd fret on the 6th string, you now move your barring finger down to the 5th fret. All your subsequent chords will move up two frets too.

If you want to lower the key by one whole step, so to F, you go two frets down. So from the 3rd fret to the 1st fret.

This will work for the major and minor chords, or any other chords that are in the key, or expressively outside the key. As long as you know the moveable chord shape, you’ll have the right chord.

Immovable Chords (e.g. Basic Open Chords)

For chord shapes that aren’t moveable, it can become a little more tricky to “mindlessly” change the key. So if you’re in G, with a simple progression like, G, Em, C, D, but you want to be in A, you need to think about changing the chords you’re playing. But you still only go up two.

So those chords in A would be, A, F#m, D, E. If you aren’t used to playing in sharps which are more common on the guitar, and flats for those occasions where they’re required by the key, it can confuzzle you a bit.

Here would be the chromatic scale (you play all the notes in between too) from C to C. I’ve picked C because C major has no sharps or flats normally. If you play piano, this will be easier to visualize.

The black keys are sharps and flats. The C is the white note on the left of the grouping of two black keys.

Chromatic scale starting at C:

C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B, C

So you’ll notice that there actually isn’t a sharp between E and F, and B and C. This is why, when you go up two chords, you need to include the sharps. Because Fm, isn’t two spaces up from Em, and the key of A major, has no F in it. Only F#.

Other than that, it’s pretty simple. It works nicely on the guitar when you go up two frets with barre chords, because each fret counts as a semitone, which is what the sharps and flats are.

So remembering this as you transpose up and down with open chords is helpful.

Use the Circle of Fifths

The circle of fifths is my preferred method when a capo isn’t an option. I just found it easier to memorize the keys like this and use this in conjunction with counting the semitones up or down. This is because it’s an easy way for me to remember which chords will be sharps or flats.

Notice how the keys are sitting as if positioned on a clock. The left side is for flats (less common for guitar), and the right is for sharps. You’ll see they overlap at the 6 o’clock position.

The outer circle is the major keys and the inner circle is the minor keys. Where you are on the clock determines how many sharps or flats you have. It’s much easier on the sharp side since the flat side mirrors the right-hand side clock numbers.

So say you’re in C. This key has no sharps or flats. The 12 o’clock position is 0. But you want to play in the key of E. Playing A-shape barre chords only or moveable chords with the root on the A or D string would make this simple. But say you want to stick to basic open chords or a mix.

E is at the 4 o’clock position. This means there are 4 sharps. The cool thing about sharps are that they follow the exact same order all the time.

F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, B#

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

So the first four will be the sharps in the key of E. F#, C#, G#, D#. So if you have any of these chords, so when you’re counting up, remember, it’s not a Fm, or Cm, it would be F#m and C#m, which are pretty common when playing in E.

There is a rhyme you can use to remember the order. Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle.

And yes, E# and B# would technically be F and C. But in key signatures, so that we know for sure the key we are in, we have to write E# and B#.

For the flats, which you may come across for example in the key of F which if you look at the circle of fifths, has one flat, you need to remember this order.

Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, Fb

1 1 3 4 5 6 7

And yes, technically Cb and Fb are B and E respectively, for the purpose of writing the key signature, we use Cb and Fb.

The rhyme you can use here is Be Early And Don’t Get Cold Feet.

So count up or down as you would normally, but use the circle of fifths to remember which chords will be sharps or flats.

Conclusion

Using these tips will make transposing chords a lot easier. There’s no need to strain your voice or have embarrassing cracks when you can just change the key to a range that’s more comfortable. You’ll also know what to do when you’re playing a gig or just playing along with a singer, and they say, I want the song in this key, or we need to go up or down this many steps.

Happy jamming!

Cheanné Lombard lives in the home of one of the new Seven World Wonders, Cape Town, South Africa. She can’t go a day without listening to or making music.

Her love of music started when her grandparents gave her a guitar. It was a smaller version of the full-sized guitars fit for her little hands. Later came a keyboard and a few years after that, a beautiful dreadnought guitar and a violin too. While she is self-taught when it comes to the guitar, she had piano lessons as a child and is now taking violin lessons as an adult.

She has been playing guitar for over 15 years and enjoys a good jam session with her husband, also an avid guitarist. In fact, the way he played those jazzy, bluesy numbers that kindled the fire in her punk rock heart. Now she explores a variety of genres and plays in the church worship group too and with whoever else is up for a jam session.