As a beginner guitar player, you probably started off by learning the major, (natural) minor and pentatonic scales. After all, these are the most common ones in the Western world. They’re easy to learn and can be transposed (moved up or down) to any key. They’re also used in most genres of guitar music.

But there’s a whole world of scales beyond the basics. Ones that can help you experiment with different notes and create memorable licks. This is where the whole tone scale (WTS) comes in.

The WTS tends to be more popular with classical pianists than modern guitarists. But it isn’t unheard of in experimental jazz, blues, funk and rock.

It may sound a bit strange at first. But learning this unusual scale can add a unique flavor to your guitar playing.

Contents

First Things First

Before we start looking at the WTS, let’s start with a bit of music theory. This way, you’ll understand how it’s formed and how each note contributes to its one-of-a-kind sound.

What is a scale?

A scale is a sequence of notes organized by pitch. It begins and ends with the same root note at different octaves (frequencies).

Let’s start with the C major scale. It contains these notes –– C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C. This first C is at a lower frequency, while the second C is at a higher frequency. The other notes are in between, with D at a closer pitch to the lower C and B at a closer pitch to the higher C.

This C major is arranged in an ascending pattern. You can also play it as a descending pattern, from a higher frequency to a lower one –– C, B, A, G, F, E, D, C.

The C major scale in standard notation, ascending and descending.

The spaces between notes are measured by intervals. These are the intervals in the ascending C major:

- C to D: major 2nd

- C to E: major 3rd

- C to F: perfect 4th

- C to G: perfect 5th

- C to A: major 6th

- C to B: major 7th

In the descending C major, these intervals would reverse direction. C to B would be a major 2nd, C to A a major 3rd, and so forth.

Finally, each note is given a number based on its scale degree (position in the sequence). In C major, for example, the D note is called the 2, while the B is the 7. The only except is the C itself, which is usually called the root note.

How do you play a scale?

As you can see, C major contains 7 notes (excluding the Cs at different octaves). However, there are actually 12 different notes that you can play in Western music –– C, C♯ / D♭, D, D♯ / E♭, E, F, F♯ / G♭, G, G♯ / A♭, A, A♯ / B♭, B. Each of these notes are a half step (also called a half tone or semitone) away from each other.

Chromatic scales contain all 12 notes, organized in a different sequence, depending on the root note.

The C chromatic scale, ascending (Created using Flat).

However, most others limit the number of notes you use, so you can achieve a specific sound. For example, diatonic scales (like major and natural minor) use the 7 notes that create the most consonance (pleasant sounds), with just a hint of tension. They do this through a combination of half steps and whole steps (also called whole tones).

The whole step/half step major sequence is W W H W W W H. The minor sequence is W H W W H W W.

Luckily, these steps are easy to visualize on guitar fretboards. Each half step is one fret apart and each whole step is two frets apart.

Let’s say you wanted to play C major, starting on your 5th (A) string. You would begin by playing the 3rd fret to get a C. Then, you’d slide up two frets for a D, two more frets for an E, one more fret for an F, and so on.

Of course, most guitarists play scales using multiple strings. But for now, it’s a good idea to stick to just one string to visualize the difference between half steps and whole steps.

What is the whole tone scale?

As we saw in the last section, diatonics consist of two half steps and five whole steps. However, the whole tone scale contains (you guessed it!) only whole steps –– W W W W W W.

This makes the WTS a hexatonic (6-note) scale, with nice even symmetry. You can also think of it as a chromatic scale, but doubled.

Let’s go back to C chromatic. If we apply the whole step formula, we get these notes for the C whole tone series –– C, D, E, F# (or G♭), G# (or A♭), A# (or B♭).

The intervals are…

- C to D: major 2nd

- C to E: major 3rd

- C to F#: tritone (also called an augmented 4th or diminished 5th)

- C to G#: augmented 5th (or minor 6th)

- C to A#: minor 7th

Although WTSs only have 6 notes, we usually call the notes by their corresponding major scale degrees. For example, A# is the 6th note in the C whole tone series. However, it’s usually called the ♭7 instead of the 6. This is because A# / B♭ is the flatted 7 note of the C major scale.

The 6 scale degrees of the C series are:

- C: 1

- D: 2 (or 9)

- E: 3

- F#: #4 (or #11)

- G#: #5

- A#: ♭7

Sometimes, scale degree 2 is called the 9 and #4 is called the #11. This is because extended guitar chords like 9ths and 11ths are common in jazz, funk and related genres. The 9 and 11 tell us that the 2 and 4 should be played at a higher octave than the other notes. Otherwise, they would be drowned out by the 5 and 7.

One unique feature of the WTS is that you can only transpose it once. The D, E, F#, G# and A# scales all contain the same notes as the C WTS. However, if you slide any of these notes up or down by one half step, you can access the other whole tone series –– C# / D♭, D# / E♭, F, G, A, B, C# / D♭.

This other series is usually called the G whole tone scale. After all, G is one of the most common guitar keys, aside from C.

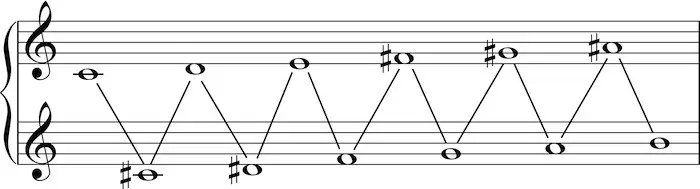

The C (top) and G (bottom) WTS (“Whole tone scales diagram” by Hyacinth / CC0).

Scale Patterns

Luckily, the WTS is easy to play on guitar. You can slide a moveable pattern up and down the fretboard, using the first note you play on the 6th string as your root note.

Any note from the C whole tone series would work as a root. But to keep it easy, let’s start with a C note on the 8th fret.

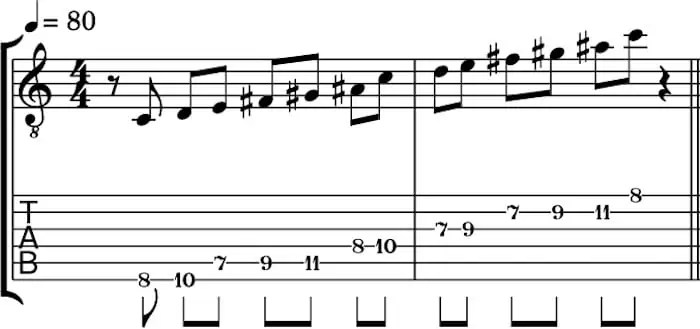

The moveable whole tone scale pattern for guitar.

To access the notes from the G series, simply slide this pattern up or down one fret. Or, if you want the G as the bass (lowest) note, you can slide it down to the 3rd fret.

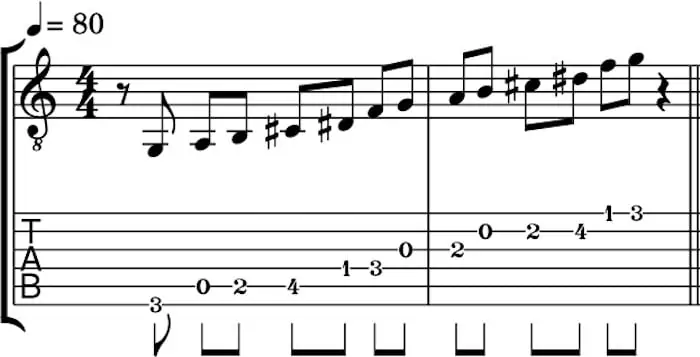

You can also play both series in open position, using (mostly) the 1st-4th frets of your guitar.

The C whole tone scale for guitar in open position (Created using Flat).

The G whole tone scale for guitar in open position.

Once you get comfortable with these common patterns, you can start experimenting with other variations.

When to Use It

Now that you know what a WTS is, you might be wondering when you would ever use such a strange series of notes.

It all boils down to what guitar genres you like to play and what emotions you want to convey in your music.

Whether you play classical, steel-string acoustic or electric guitar, the WTS is surprisingly versatile –– as long as you know how to use it properly.

Common genres

The first known use of a WTS was in 1662, when composer Johann Rudolf Ahle wrote a hymn called Es ist genug (“It is enough”). Other Baroque/Classical superstars like Bach, Mozart and Schubert composed with it too. But it’s most famously associated with later Romantic and Impressionist composers like Mikhail Glinka, Franz Liszt and especially Claude Debussy.

Debussy’s “Voiles” (1909) is almost 100% based on whole tone piano melodies.

Indian classical music also has some rāgas (melodic structures) that are similar to the Western WTS.

Not into classical music? Don’t worry. The WTS is also a helpful improv tool in guitar genres like jazz, funk and prog rock.

Still, perhaps its most famous use is for dream/flashback sequences in movies and TV shows.

This classic vibraphone run is the perfect example of a C whole tone scale.

Overall feeling

Because the WTS is completely symmetrical, it has no tonic (root note) in the traditional sense. Whether you play the C series starting on a C, a D or even an A#, it all sounds the same. This gives it a vague, mysterious, wandering sound.

Some other adjectives used to describe the WTS are “dreamy”, “indistinct”, “disorienting” or even “ominous”. On one hand, it makes you feel like you’re floating through space. But on the other, it’s full of unresolved tension.

The WTS is full of contradictions. It’s dreamy but nightmarish, neutral but tense, and steady but unclear.

Above all, it can add colorful lead and rhythm guitar parts that wouldn’t be possible with any other type of scale.

How to Use It

Now comes the fun part –– using the WTS to modify chord progressions, experiment with triads and arpeggios, and write your own guitar solos.

Here are some basic improv rules to guide you…

Don’t limit yourself to major 2nd intervals

If you write a guitar lick using only ascending or descending major 2nds, you’re basically copying TV dream sequence music.

Instead, try shaking things up with some major 3rds, tritones and other intervals. Of course, you can still add some major 2nds here and there. Just don’t rely on them exclusively.

Do make use of the #4 and #5

These are the two notes that give the WTS its unique identity. By ignoring them you risk soloing in Mixolydian mode instead –– which is a major scale with a ♭7 note.

The #4 and #5 are also the notes that create the most tension. After all, aside from the root, the natural 5 is the most consonant note in both major and minor scales. By removing the 5 completely and playing around with the half steps directly above and below it, you surprise listeners –– leaving them wondering what will happen next.

The #4 and #5 are especially powerful when they’re played as intervals with the root note. The augmented 5th tends to be rare in popular music, because it has a surprisingly large leap between pitches. But it can still add an unexpected touch to your guitar melodies.

Shorter-distance tritones are more common, especially in blues and jazz. A word of warning though –– these intervals are the most dissonant (clashing) in Western music. This is why it’s often called “the devil’s interval”.

Do remember your tritones

Another unique feature of the WTS is that it contains 3 tritones. They’re found between these notes:

- 1 and #4

- 2 and #5

- 3 and ♭7

Jazz rhythm guitar players often combine the 3 and ♭7 into a moveable dyad (two-note) shape called a tritone sub. But the other two can also lend themselves to interesting rhythms.

This first tritone sub (left) can be applied to any string, except the 2nd. For the 2nd-string-root tritone sub (right), you’ll need to raise the finger on your 1st string by one fret. In both these shapes, the root note is on the bass string and the #4 is on the treble (higher) string.

Do include aug triads and arpeggios

Tired of playing around with moveable scale patterns? Why not shake things up with some augmented triads?

These three-note chords fit comfortably with the WTS, because they share these notes in common –– the 1, 3 and #5. Because of this raised 5, aug triads are often marked with a plus sign (ex: C+) in guitar tabs.

Although you can fret them as full barre chords, I find that they’re easiest to work with as three-finger shapes on the top 4 strings.

Moveable aug triads with roots on the 4th (left) and 3rd (right) strings. This first triad corresponds to a 6th-string-root barre chord (imagine the barre is above the index and middle fingers). The second triad corresponds to a 5th-string-root barre chord (imagine the barre is above the index finger).

The best part is that you can play an entire WTS using just two aug triads, two frets apart.

Arpeggiating (isolating each individual note from a chord) can be a great way to add a melody to your song–– all while staying in simple triad shapes.

Or, for an extra challenge, you can play aug arpeggios by isolating the 1, 3 and #5 notes from your standard WTS pattern. You can even add the ♭7 to turn them into augmented 7th arpeggios.

Don’t forget about the 9

The 9 (or 2) isn’t unique to the WTS. It appears in most other diatonics.

However, 9th chords are essential for many jazz and funk guitar songs. By highlighting scale degree 9 in your whole tone licks, you can easily incorporate them into 9th-chord progressions.

For even more consonance with the #4 and #5 notes, you can change your guitar chords from 9ths to 9#11ths or 9#5ths.

Do improv over 7th chords

7th (or dominant 7th) guitar chords consist of the following notes –– 1, 3, 5, ♭7. Except for the natural 5, all of these notes fit comfortably into the WTS.

When you solo over a 7th chord, you can use the chord tones (1, 3 and ♭7) to add consonance and the color tones (2, #4 and #5) to add dissonance. Over a C7, for example, the chord tones are C, E and B♭, while the color tones are D, F# and G#. Combining all 6 notes leads to interesting melodies, with rising and falling tension.

To start off, I would recommend soloing over a basic 12-bar blues progression. This way, you can experiment with three different 7th chords.

This video is a strong example of whole tone soloing in the key of G.

As a rhythm guitar player, you can also change the progression to include jazzy 7#11th, 7♭5th and/or 7#5th (aug7) chords. This is a good way to minimize any unwanted dissonance and create a smoother fit with the whole tone melody.

Do improv over the V7 chord

Whether you’re playing a I IV I V IV I V blues progression or a ii-V-I jazz progression, the V chord naturally produces a lot of tension –– especially if it’s a 7th.

Let’s say we’re playing a iim7-V7-Imaj7 progression in the key of C. The ii chord would be Dm7 and the I chord would be Cmaj7. Meanwhile, the V chord would be G7, with the notes G, B, D and F.

In a major guitar key, scale degrees 2 and 7 have the most pull to resolve to the tonic. In the key of C, these notes are D and B –– both of which appear in the G7. Therefore, a movement from G7 to Cmaj7 creates a buildup of tension, followed by a satisfying release.

This tension is even greater with a V7 chord, thanks to the tritone between the 3 (B) and ♭7 (F). This makes the G7 feel unsteady, creating an even greater pull to resolve to the C.

What does this have to do with the WTS? Well, if you want to amp up the tension even more, you can use regular diatonic or pentatonic licks over the iim7 and Imaj7. Then, switch to whole tone licks over the V7. By using your chord and color tones from the G series, you’ll create an even more satisfying release when you end on the Cmaj7 tonic.

These same rules apply to 12-bar blues progressions during the turnaround –– the V IV I V chords at the end of each passage.

Don’t use the same root note in minor key songs

So far, we’ve only talked about songs in major guitar keys. But what about minor guitar keys?

The good news is that you can play a WTS over a minor chord progression. Only, you’ll need to use the other whole tone series –– not the one that shares the same root note as the chord. This is because the defining note of minor keys is the ♭3. Playing the corresponding WTS, which has a natural 3, would sound out of place.

Let’s take C natural minor, which has the notes C, D, E♭, F, G, A♭, B♭, C. The C series shares four notes in common –– C, D, A♭ / G# and B♭ / A#. But it has an E instead of an E♭.

In contrast, the G series shares the E♭, as well as the G. Although it doesn’t contain the C root note, it covers the other two Cm chord tones. Therefore, the G series is the better choice for a killer guitar solo.

Don’t use the whole tone scale exclusively

But wait? Didn’t Debussy write a whole song using the WTS? If he can do it, why can’t everyone?

If your goal is to become the guitar virtuoso equivalent of Debussy, then by all means, go ahead. But if you want to work on developing your own style, it’s better to use the WTS in moderation. This way, you can use it in certain sections for maximum impact, without overwhelming (or eventually boring) your listeners.

The Whole Tone Scale in Action

The WTS isn’t super popular in modern guitar music. But you can still hear it several classic songs.

Some of the best known examples are:

- “In a Mist” by Bix Beiderbecke: this bouncy jazz standard may not have any guitar in it. But the piano runs still capture the Impressionist-inspired tension you can create by playing with #4s and #5s.

- “Four in One” by Thelonious Monk: Thelonious Monk is probably the best known supporter of the WTS. The legendary jazz pianist uses it throughout “Four in One” to connect the A and B sections of the song.

- “One More Red Nightmare” by King Crimson: this prog rock band is famous for experimenting with non-traditional scales. Guitarist Robert Fripp uses the WTS extensively in “One More Red Nightmare” to complement the tense, plane-crash-inspired lyrics.

- “You Are the Sunshine Of My Life” by Stevie Wonder: this iconic electric piano intro consists of a C series run. By connecting listeners to that dream sequence feeling, it provides a strong lead-in to a song about endless love.

Whole tone melodies are easy to hear in Stevie Wonder’s soul classic, “You Are the Sunshine of My Life”.

Related Scales

The WTS is one of a kind. But it’s not the only guitar scale that breaks the diatonic major or minor mold….

- Lydian mode: this variation of the major scale has a #4 note. This creates a tritone with the root note, similar to the WTS. There’s also different variations on the Lydian mode that include whole tone notes. For example, the Lydian Augmented has a #5, while the Lydian Dominant has a ♭7.

- Pentatonic scale: sonically speaking, pentatonics have little in common with WTSs. But these five-note scales also skip the half tone intervals of diatonics. The major pentatonic includes the 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 notes of the major scale, while the minor pentatonic includes the 1, ♭3, 4, 5 and ♭7. Overall, the major pentatonic shares more notes with the WTS.

- Blues scale: blues scales are basically pentatonics with an additional chromatic note. In the major blues, it’s the ♭3. In minor blues, it’s the ♭5. The ♭5 creates a tritone with the root note. This gives the minor blues scale a closer feel to the WTS than a normal minor pentatonic.

Final Thoughts

The WTS may not seem as useful for guitar players as its more popular cousins, like the pentatonic and blues scales. But for classical, jazz, funk and fusion players, this is one of the best (not to mention easiest) ones to learn.

Adding a whole tone guitar lick can be an unexpected way to inject your song with moody, dreamy flavor. Especially when you pair it with the right 7th, extended or augmented chord progression.

Just remember –– when it comes to the whole tone scale, less is more (no matter what Debussy tells you)! Trust your ear to guide you. If the lick sounds too bland, amp up the whole tone notes. If it sounds too tense, return to some familiar major or minor sounds.

Have fun!