Seventh chords are a great way to spice up any chord progression. They might sound somewhat intimidating and complex just by the name, but that’s just on the surface! In fact, seventh chords can be easy to add to your chord repertoire, and fun to play! Today we’ll be going over the Em7 chord, how it works, and how you can begin playing it right now. Let’s dive in!

Contents

How to Play the Em7 Chord

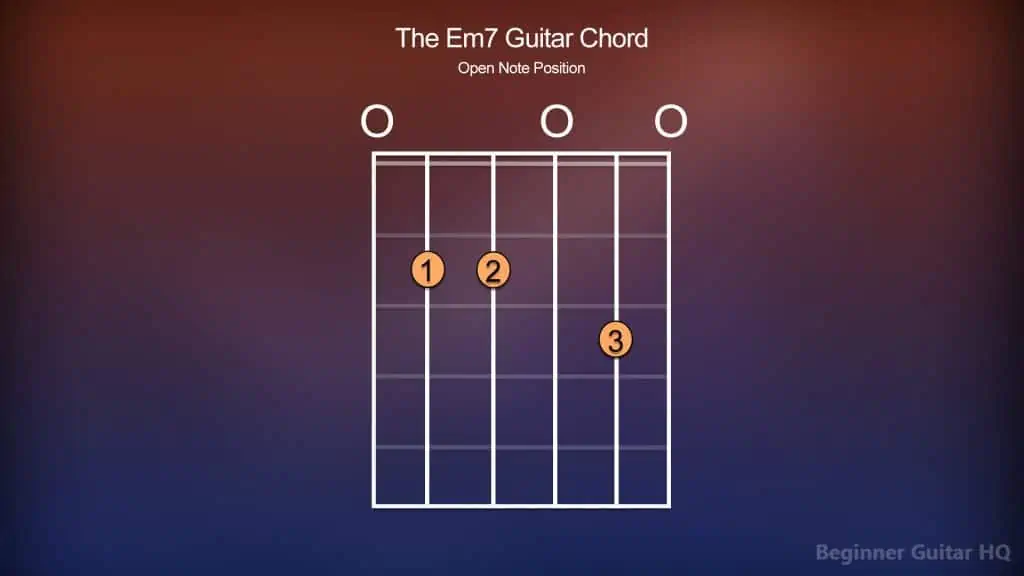

Are you excited to learn how to play the Em7 chord? Let’s begin with a few chord charts:

The Em7 chord chart from open note position.

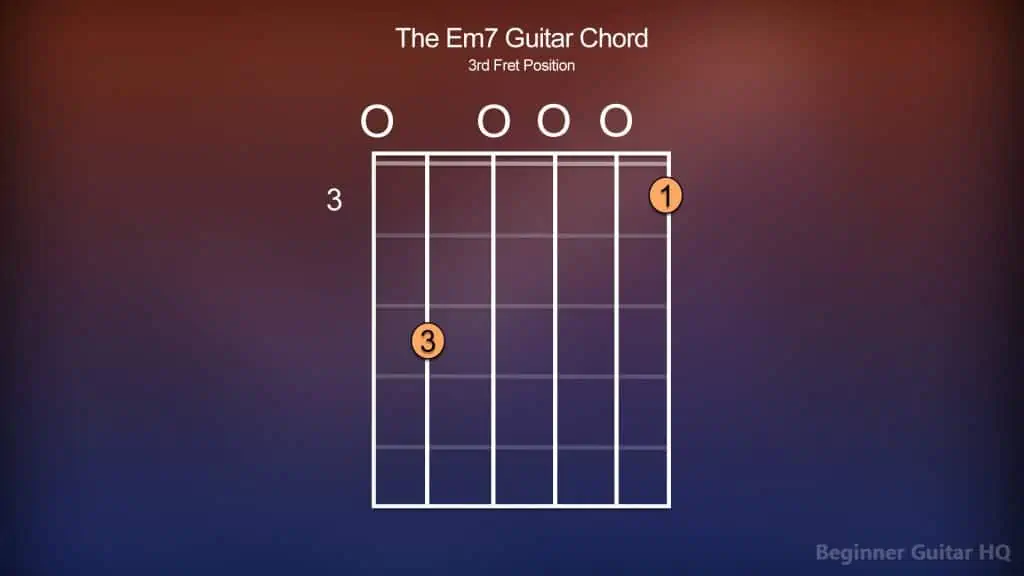

The Em7 chord chart from the third fret position.

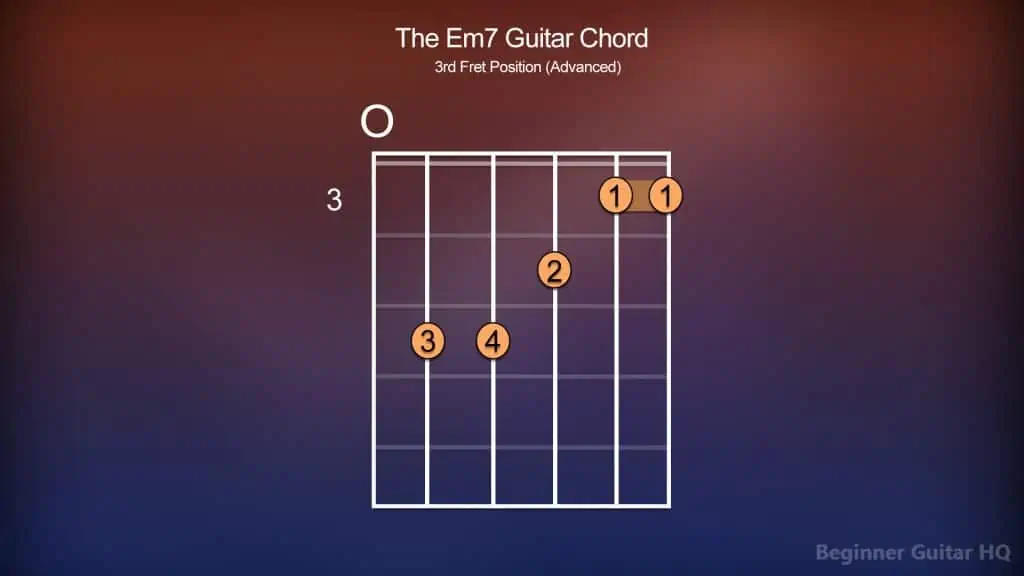

The advanced Em7 chord chart from the third fret position.

Trouble With Chord Charts?

Chord charts can look a little intimidating, but they are very easy to learn! Let’s give it a quick rundown. First, you’ll notice a box containing several vertical and horizontal lines; this represents our fretboard. Now, each of the vertical lines you see running down the fretboard is meant to represent a different string on the guitar. From left to right you have your low E string, A, D, G, B, and high E strings. The horizontal lines, however, are meant to separate one fret from the next.

Within the frets, you’ll see a number that is meant for “finger placement”. Each number represents a different finger, and where it’s meant to be on the fretboard in order to complete the chord. The number “1” is for your index finger. The number “2” is for your middle finger. The number “3” is for your ring finger. Finally, the number “4” is for your pinky finger.

Over the top of the fretboard, you may notice an “O” or an “X”. An “O” represents a string that is to be played, but not fretted. An “X”, however, means that the string is to not be played to complete the chord. In some cases, you might even notice a number to the left of the fretboard, which is meant to indicate the fret you’re starting on for the chord. This happens in cases where you need to position your hand higher on the fretboard to complete the chord. That’s all there is to it!

Breakdown of the Em7 Chord

The abbreviation Em7 is short for what we know as the “E minor seventh” chord. You can often find seventh chords used in the genres of Jazz and Blues music, however, it’s not uncommon to find them in the likes of hip-hop, and deep-house music, where the artist wants to capture a similar vibe.

So what exactly is a seventh chord? In a nutshell, a seventh chord contains our standard triad of notes; our tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees, with an additional interval of a seventh from the tonic placed on top! Confused? That’s okay because we’ll run through it to give you a better understanding of it all.

The Key of E Major

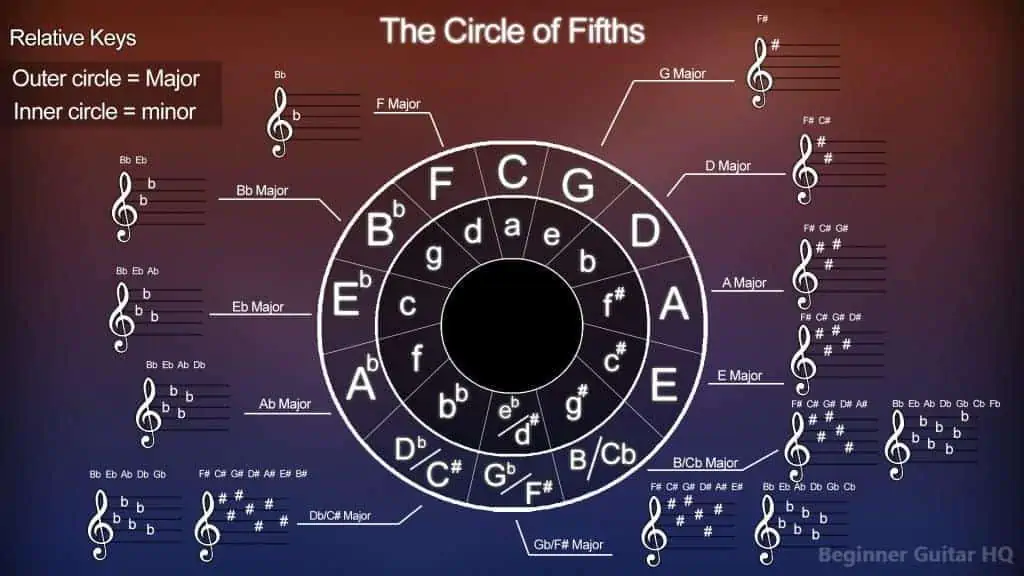

First, we should get a better understanding of what our key is. Essentially, the key is our home, in this case, it would be E minor. Every key contains its own key signature. A key signature is represented by a collection of sharps (#) or flats (b), often found at the beginning of a piece of sheet music. A note that is sharp will raise the note by a semitone, while a note that is flat will lower the note by a semitone. When starting out, however, it’s best to consult the circle of fifths to better understand how this works.

Diagram of the Circle of Fifths, displaying all of the most commonly used key signatures.

The circle of fifths is a wheel-shaped diagram displaying all of the most commonly used keys and their corresponding key signatures. You will immediately notice that there are two rings. The inside ring, which we will be focusing on, contains all of our minor keys, while the outside ring contains all of our relative major keys (keys that share the same key signature). Off to the sides, you will notice a collection of sharps or flats on some lines; these are our different key signatures. As you go clockwise along the wheel (starting from C Major/A minor), you’ll notice that each key gains an additional sharp. On the other end of the spectrum, as you go counterclockwise along the wheel, each key gains an additional flat. Essentially, the notes on the sharp half of the wheel will look like this:

A = No sharps or flats.

E = F

B = F, C

F# = F, C, G

C# = F, C, G, D

G# = F, C, G, D, A

D# = F, C, G, D, A, E

A# = F, C, G, D, A, E, B

The circle of fifths is great, but you probably don’t want to use it all of the time. So how are these sharp and flat notes determined? The best way to understand this sequence is by the acronym: FCGDAEB. This stands for:

“Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle”

Each first letter of each word in this acronym represents a different note to be sharp. For instance, if we know that D major has two sharps in its key signature, then we can use our fingers and say, “Father, Charles..” and know that these two sharps are F and C sharp. Let’s try it again, but with C# minor. Looking at the circle of fifths, we know C# minor has four sharps. This time we’ll go, “Father, Charles, Goes, Down…” So the sharps used in the key of C# minor are F, C, G, and D.

Now, let’s try it with E minor. How many sharps does E minor have? That’s right, one sharp. We will use our fingers, (not that we have to in this case) “Father…” So it’s only F sharp. With this information, we can now lay out our E minor scale:

E > F# > G > A > B > C > D > E

Minor scales have a pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) that they all follow. Here is the sequence:

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

If you look at our E minor scale above, you will see it follows this pattern accurately. E > F is normally a semitone apart, however, F becomes F# making them a tone apart. If we look at the first interval in our tone/semitone pattern, you’ll see it’s a tone (T). However, because F became F#, it’s now become a semitone (S) apart from G. The rest of the scale bends to this pattern.

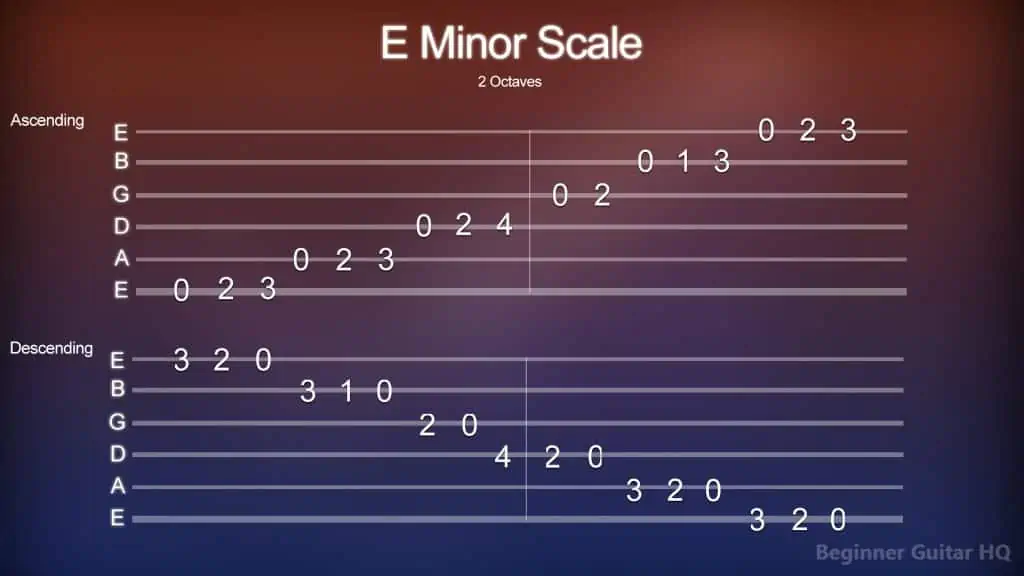

If you’d like to hear how our E minor scale sounds, here is some tablature of it below:

Tablature of the E minor scale on the guitar, ascending and descending.

Trouble With Tablature?

If you’re new to tablature, don’t fret! It’s fairly easy to learn. Let’s bring our attention to the six horizontal lines, as each of these represents a different string on the guitar. The letters to the left of these lines indicate the line’s corresponding string. From the bottom to the top, we’ve got our low E string, followed by the A, D, G, B, and high E strings.

On these lines, you will see different numbers indicating which fretted note you’re supposed to play on that string. So for instance, if you see the number “2” on the A string, then that means you’re to play the second fret of the A string. If you see the number “4” on the G string, then that means you’re to play the fourth fret of the G string. If, however, you see the number “0” this implies that you are to play an open note on this string (a string meant to be played, but not fretted). That’s all there is to it!

Be aware that tablature, while easy to learn, comes with some minor downsides when compared to its more detailed cousin, musical notation. With tablature, you get a very direct, yet somewhat vague way of how to play your favorite songs. In fact, in a lot of cases, it’s your job as the musician to use your ear to play the minor details of a song as they were intended. However, in some cases, you might be fortunate enough to stumble on tablature explained in greater detail. For instance, here are some symbols used to explain how certain parts of tablature are meant to be played:

H = Hammer-on

P = Pull-off

B = Bend

X = Mute

PM = Palm Mute

\ = Slide Down

/ = Slide Up

~~~ = Vibrato

It’s also of great importance to exercise good habits while playing guitar. One thing not often expressed is the importance of good fingerwork. You should always plan ahead by reading whatever you’re about to play so that you use the right fingers for the right frets. For instance, let’s say you were practicing a song, and the lowest you would go on the fretboard was to the 2nd fret, and the highest you would go to would be the 5th fret, but your first note is on the 3rd fret. What finger would play the first note? Well, you would probably use your middle finger on the first note. Following that, your index would play anything on the 2nd fret, your ring finger for anything on the 4th fret, and finally, your pinky finger for anything on the 5th fret.

The idea is that you want whatever you’re playing to fit within the space of your hand. Good fingerwork can make all the difference!

Scale Degrees

Did you know that every note within our scale has a unique purpose? In fact, every note within our scale also has a unique identifier based on which degree it falls under within the scale. Here are the different degrees of E minor:

- E = Tonic (1st Degree)

- F# = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

- G = Mediant (3rd Degree)

- A = Subdominant (4th Degree)

- B = Dominant (5th Degree)

- C = Submediant (6th Degree)

- D = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

- E = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

Our first degree, the tonic can be thought of as our home, our tonal center where things tend to resolve. The second degree, the supertonic, however, is more of an interchangeable degree with our fourth degree as they share two of the same notes. The mediant is our third degree and is often used to expand from the tonic, thereby drawing it out as they too share two of the same notes. Next, we have our fourth degree, the subdominant, which is one of our more important degrees. The subdominant acts as a tension builder, holding one note in common with our tonic, which happens to be our root note. Naturally, the subdominant will want to progress to our fifth degree, the dominant. The dominant, next to our tonic is the most important degree, where tension is at its peak within our progression. Our dominant also shares one note with our tonic, however, it is not the root note. From our dominant, we naturally like to resolve back to our home, the tonic. Next, we move to our sixth degree, the submediant. Our submediant also shares two notes with our tonic, making it another great degree to expand from our tonic with. Lastly, we have our seventh degree, the leading tone. For our seventh chords, this is a very important degree, as this gets stacked on top of our triads. From a chord progression standpoint, however, being right below the tonic an octave higher from where we began, this degree holds a lot of tension. In fact, try playing a C major scale and ending on B. Naturally, your ears will want to hear it resolve to C.

The E minor Triad

Taking what we’ve learned from our E minor scale, as well as the different degrees, we’re going to form an E minor triad. To form an E minor triad, we have to take our first degree (tonic), the third degree (mediant), and our fifth degree (dominant), and stack them on top of each other. Within the key of E minor, these notes appear as E, G, and B.

Minor triads always have the same intervals between each note. For instance:

-

- Minor 3rd – From the 1st degree to the 3rd degree. E > G.

- Major 3rd – From the 3rd degree to the 5th degree. G > B.

- Perfect 5th – From the 1st degree to the 5th degree. E > B.

Now that we can form our E minor triad, let’s make it become an E minor seventh chord! First, we’ll take the triad of E, G, and B, but this time we’ll take the leading tone (7th degree) of our E minor scale, and stack it on top! The notes in the chord now become, E, G, B, and D. It’s as easy as that!

Finding Chords Compatible With E Minor

While we’re on the topic of triads, let’s cover how to find chords compatible with E minor. To do so, we’ll have to take our E minor scale once again, but this time, put triads on each degree. Therefore, it’ll look like this:

E minor = E, G, B (1st Degree)

F# diminished = F#, A, C (2nd Degree)

G Major = G, B, D (3rd Degree)

A minor = A, C, E (4th Degree)

B minor = B, D, F# (5th Degree)

C Major = C, E, G (6th Degree)

D Major = D, F#, A (7th Degree)

Do you remember when we mentioned how every degree of our scale serves its own unique purpose? Let’s see it in action for a couple of our tried and true chord progressions:

i – iv – v – i

For our first progression, we start at our home, the tonic, E minor. We will then move from our 1st degree to the 4th degree, the subdominant, A minor. Our A minor chord shares a note with our E minor, the note E, but adds some slight tension to our progression. Moving up to our 5th degree, the dominant, we’re now playing B minor. Our B minor chord shares a note with our E minor chord, but it happens to be the note B, moving away and adding even more tension. Next, we will resolve back to our tonic, E minor, where things are calm again. We keep playing the chord, and loop around again starting on the E minor chord. Our chord progression looks like this: Em > Am > Bm > Em

i – VI – III – VII

This chord progression starts on our tonic, E minor, once again. From our tonic, we’ll shift to our sixth degree, the submediant, C Major. Our submediant shares two notes with our E minor chord, the E and G, therefore, drawing out the tonic. From here, we’ll move to our third degree, the mediant. The mediant is another chord used to expand on the tonic, however, this will add slightly more tension as the notes it shares with our tonic don’t contain an E, but rather a G and B. Finally, we’ll shift to our seventh degree, the leading tone. Our leading tone shares no notes with our tonic, creating a lot more tension. Naturally, our leading tone will want to resolve and return back to our tonal center, the tonic. Our chord progression looks like this: Em > C > G > D

Emaj7 to Em7

We’ve covered a lot about the key of E minor, and E minor seventh chords. What about the other side of the coin, our E major seventh chord? Well, let’s cover some of the differences between major and minor:

First, going back to our key, key signature, and the circle of fifths, we’ll notice some key differences. First, E minor and E major have different key signatures, as they are in a parallel major/minor key relationship. This means that while they share the same tonic, they don’t share the same key signature. This differs from a relative major/minor key relationship, in which they have different tonics, but share the same key signature. A good example of this is E minor to G major as they both have one sharp in their key signature, F sharp.

So what is the key signature of E major? Looking at the circle of fifths, we can deduce that E major has four sharps, which are F, C, G, and D. Now let’s take a look at the E major scale:

E > F# > G# > A > B > C# > D# > E

It looks a little different than our minor scale. This isn’t just because of our key signature, but because major scales also follow a different pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) than minor scales:

T > T > S > T > T > T > S

E and F are normally a semitone apart, but F becoming F# puts them a tone apart. To follow this tone/semitone pattern, G needs to become G# to keep it a tone apart from F# now. The same occurs with C becoming C#, moving away from B, and D becoming D# moving away from C#.

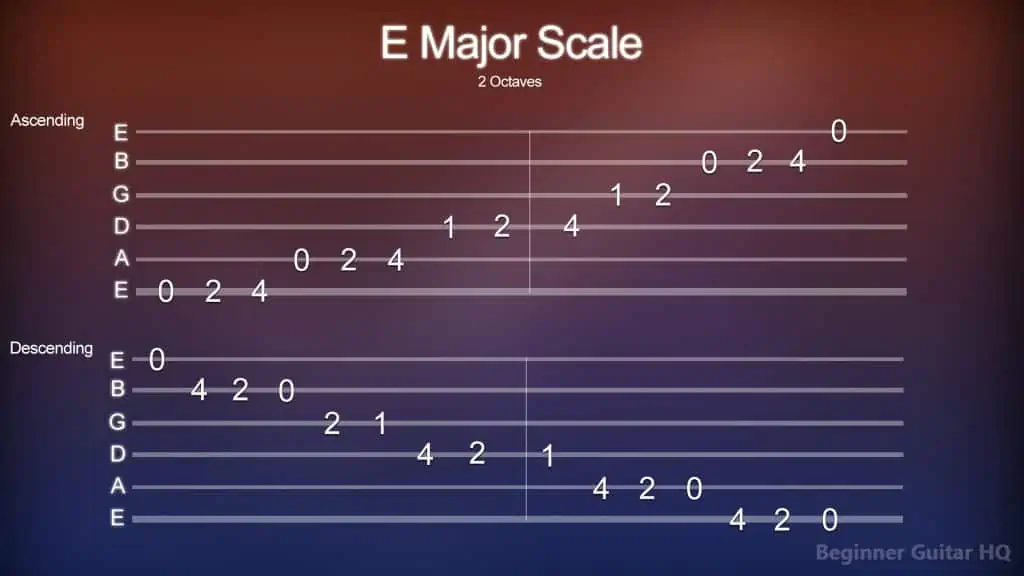

Now that we’ve gotten this all laid out, why not hear how it sounds on guitar?

E major scale tab moving between two octaves, ascending and descending.

Now, when forming an E major triad, you use the same degrees as our minor triad: tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees. However, the intervals are different. Let’s take our notes E, G#, and B, analyzing the intervals:

- Major 3rd – From our first degree to our third degree. E > G#.

- Minor 3rd – From our third degree to our fifth degree. G# > B.

- Perfect 5th – From our first degree to our fifth degree. E > B.

Did you notice anything different when compared to our minor triads? In our minor triads, the first interval from the first degree to our third degree was a minor 3rd. From our third degree to our fifth degree, the interval was a major 3rd. In a major triad, this, however, gets flipped! Instead, we have a major 3rd from our first degree to our third degree and a minor 3rd from our third degree to our fifth degree. The perfect 5th, however, remains the same.

Now, let’s turn this into an Emaj7 chord. First, we take our existing E major triad of E, G#, and B. Next, we add the seventh degree of our E major scale, which is D#. Therefore, the notes in an Emaj7 chord are E, G#, B, and D#.

Conclusion

Now you have everything you need to get started with your Em7 chord! Learning a new set of chords can inspire and spark creativity in writing music, and possibly lead you toward further expanding your chord repertoire. How do you plan to use seventh chords? Will you go beyond and learn ninth, eleventh, or even thirteenth chords? There are so many possibilities. What are you waiting for?