Extended chords were probably not among the first chords you learned when you initially picked up the guitar. Unfortunately, most beginner guitarists master just their open chords and basic barre chord shapes without progressing through to more harmonically interesting altered chords.

That’s a real shame — extended chords are some of the most unique and cool chords you can play on guitar; taken together they provide you with far more tonal “colors” than your standard major and minor chords do. The prominence of extended chords in more theory-centric genres such as jazz and experimental music makes them a crucial category to learn for many new players as well.

Whether you’re a songwriter looking to spice up your new compositions or a budding guitarist who loves to play jazz, learning extended chords will improve both your physical playing skills and your sense of tone, harmony, and feel. And contrary to popular belief, learning extended chords doesn’t require extensive knowledge of music theory — just a bit of practice and attention.

Contents

What Are Extended Chords?

To begin our discussion of extended chords, it’s important to clearly understand what these chords are. We’ll keep it as straightforward as possible to ensure players at all levels can understand, but there will be some theory involved in the explanations.

Misconceptions About Extended Chords

Many guitarists regard extended chords as some sort of jazz voodoo, or as a set of voicings that are impossible to finger and even more difficult to remember. In reality, however, that’s not the case.

Like standard barre chords, extended chords fall into patterns that you can play up and down the entire neck. True, there are more voicings possible with extended chords than with standard barre chords, which tend to only involve the root note, major or minor third, and fifth. Some barre chords (such as power chords) don’t even contain the third!

However, you only really need to know a couple voicings of each extended chord to begin working them into your own playing. One voicing of each extension on the sixth string and one on the fifth string will do.

Another complaint often leveled against extended chords concerns their confusing names. If there are only seven notes in an octave — and only 12 distinct named notes playable in Western music — how can extended chords reach all the way up to a 13 chord? If you’ve thought about this situation and came away puzzled, the real answer is actually much simpler than you might have expected.

Extended chords are infamous for their more complex fingerings, though many extended chords aren’t hard to fret.

Basics of Extended Chords

If you visualize a one-octave scale (choose a major scale for simplicity’s sake), you’ll recognize that there are seven different notes, with the eighth note (the octave) returning to the same note as the first degree of the scale. Now extend that scale up for a second octave.

Picturing the two octaves together gives us 15 total notes (while you might expect sixteen, the eighth note doubles as the end for the first octave of the scale and the root for the second octave). Extended intervals like the 9th, 11th, and 13th are created simply by playing an interval with a note more than an octave above the root.

Technically, these are the same notes as could be found in the first octave of the scale. The ninth of a C major scale, for example, is a D note — the same note as the second degree. However, these two notes are far different in pitch; playing the ninth together with the root produces a much different sound than playing the second with the root.

You may wonder why we only use the 9th, 11th, and 13th as extended chords. Why don’t we also refer to a chord with, say, the 12th scale degree as a maj12 chord? The answer comes in the original chord triad.

As we mentioned above, a basic chord triad contains the root, third, and fifth of any given chord. The seventh is another common addition to barre chords within the first octave; we refer to chords with the seventh included as dominant seventh, major seventh, or minor seventh chords (depending on the particular character of the chord).

Many extended scale degrees share a common note with the root, third, fifth, and seventh found in standard non-extended chords. Because these notes are already contained within a standard chord triad, playing them once again an octave higher doesn’t affect the central essence of that chord. A C major chord with an added 12th (equivalent to the fifth) is still just a plain old C major chord.

By contrast, the 9th, 11th, and 13th degrees aren’t commonly found in basic chord triads. Including them in the chord creates a different sound than just playing the standard barre chord — notating these new chords as special extended chords conveys the difference in tone between the two options.

Extended Chords Versus “add” Chords

Technically, both extended chords and “add” chords are extended chords — after all, they both use scale degrees beyond the octave. However, the two different notations signal two different chord shapes. It’s important to know the difference to prevent confusion before you begin working extended chords into your playing.

The chords that are traditionally referred to as “extended chords” include the root, third, fifth, and seventh of a chord in addition to an extended note (the ninth, eleventh, or thirteenth). As you move up the hierarchy of extended chords, you can also add extra notes on from lower scale degrees.

For example, a standard 9th chord includes the root, third, fifth, seventh, and ninth scale degrees (or some combination of those tones). An 11th chord follows a similar pattern, but with one twist. In addition to including the root, third, fifth, seventh, and eleventh scale degrees or some combination thereof (as you might guess), an 11th chord can also include the ninth scale degree.

This is also true for 13th chords, which can include either or both a ninth and eleventh in addition to the root, third, fifth, seventh, and thirteenth. The wide variety of possible voicings for 13th chords means it’s common to eliminate some of those notes to avoid overly straining your fingers.

“Add” chords, on the other hand, are far simpler. As the name implies, they include just the basic major triad and one additional extended note. Taking an example in the key of C major, a Cadd9 chord would include just the root, third, fifth, and ninth scale degrees — in this case, a C, E, G, and D.

A Cadd11 chord would incorporate an eleventh note instead of the ninth degree used above, creating a final chord made of a C, E, G, and F. A Cadd13, following the same pattern, would substitute the thirteenth scale degree for the eleventh and end up with a chord consisting of a C, E, G, and A.

The difference between the two may seem rather quaint right now. In many cases, the two types of extended chords are basically interchangeable, especially depending on the finger position and voice leading required for the tune you’re playing.

With that being said, however, there are some key differences between the two. Normal extended chords create a stronger sense of impending resolution to the root note, thanks to the added seventh. They can also create a much smokier, darker “jazzy” sound thanks to the abundance of available notes.

“Add” chords, by contrast, are often simpler and more straightforward to play. They work great for adding a punch of harmonic color into a chord progression or for voice-leading a melody across multiple chord changes. Without the other notes found in standard extended chords, “add” chords do a better job of highlighting the specific extended note you select.

Reading chord charts requires you to know extended chord notation.

Extended Chord Notation

Extended chords may be notated in a few different ways, depending on the source you’re reading from. If you plan to sightread chord charts or want to be able to recognize and utilize extended chords at a glance, it’s important to know all of the different possible notations.

The most common form of notation for an extended chord is simply the chord name followed by the number of the extension — for example, C13. These chords can also be referred to as “dominant 13th” chords, since they build off of a dominant seventh chord (often notated the same way, for example “C7”).

Extended chords built upon a major or minor seventh chord are constructed and notated differently from their dominant cousins. A maj9 chord, for example, contains a major seventh interval along with the third, fifth, and ninth degrees of the major scale. In C major (Cmaj9 chord), this creates a chord including C, E, G, B, and D.

A dominant ninth chord, however, uses a dominant seventh interval (flatted seventh) along with the third, fifth, and ninth degrees of the same major scale. For example, a C9 chord is constructed from a C, E, G, Bb, and D.

Minor ninth chords are based off of a minor seventh chord; these include a minor third interval in addition to the root, fifth, flatted seventh, and ninth. A Cm9, therefore, is composed of a C, Eb, G, Bb, and D.

To avoid confusion between the three different types, classic extended chords are notated in the same manner as seventh chords. Dominant extended chords are simply the chord letter and extension number put together, while major and minor extended chords each receive a small additional tag between the two.

This is usually “maj” for major extended chords and “m” for minor extended chords, though some books prefer to notate minor chords with a “mi” tag rather than just using the lowercase “m.”

“Add” chords are indicated with an “add” tag between the chord letter and extension number. As discussed above, these chords don’t include the seventh or extra extended notes found in basic extended chords — quite literally, they’re just formed by “adding” one extended note to the standard root-third-fifth major triad.

Extended chords are common in gypsy jazz, often played on classical guitars like this one.

Common Uses of Extended Chords

Extended chords, while most generally found in jazz and funk, can be used for a wide variety of different functions across multiple styles of music. Here, we take a look at a few of their most common uses and traits.

Ninth Chords

Ninth chords are the most common type of extended chord. They’re by far the most similar to more standard chords — a ninth chord is simply the corresponding seventh chord with an added ninth interval.

Functionally speaking, these ninth chords are the same as their related seventh chords. The addition of the ninth note simply thickens up the mix and introduces a new dissonant tone. That extra note, however, does give ninth chords a more ear-catching aspect than seventh chords, which we hear in most major forms of popular music.

That unfamiliar character makes ninth chords a popular chord for fast strumming sections where they’ll stand out more than traditional chords. Their snappy, distinctive quality suits funk music particularly well.

The treble-heavy nature of ninth chords, and extended chords in general, meshes well with funk players’ preference for playing on the top strings of the guitar. Extended chords are easy to voice without including a lot of bass and always promise to cut through a mix.

Take a listen, for example, to James Brown’s hit “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag.” This cut, often cited as one of the forerunners of funk music, prominently features an E9 chord strummed wildly after the main vocal line. It’s that unstable, slightly dissonant sound that makes ninth chords so popular.

Another variant of the ninth chord that merits extra mention is the dominant seventh sharp nine chord — more famously referred to as the “Hendrix chord.” Though it’s been employed by other star musicians, most notably The Beatles, the 7#9 chord has become indelibly linked with Hendrix in the guitar community. This is probably due to Hendrix’s special affinity for the sound.

He used the chord in many of his songs, but the introduction to “Purple Haze” stands as one of the most famous instances. In fact, that introduction may be one of the most famous uses of a ninth chord in all of rock music. The use of the sharp ninth note creates a wailing, slightly sinister tone that sounds faintly reminiscent of a warning siren or alarm bell.

Hendrix was also prone to “tonicizing” the dominant seventh sharp nine chord — that is, using this chord in place of the more vanilla I chords found in major-key songs.

Though traditional music theory professors would regard the inherently unstable seventh chord as too off-balance to create a tonic center — particularly with the addition of the sharp ninth note — Hendrix utilized it for darker, moodier sounds where he wanted less of a firm resolution that the standard tonic major triad provides.

The angular sound of ninth chords, particularly the dominant ninth, conveys a raw and gritty feel reminiscent of the blues scale. That resemblance makes ninth chords popular among guitarists looking to imply some sort of blues feeling, whether in a jazz setting, a funk tune, or a hard rock song. Ninth chords are common in blues progressions as well as in “bluesy” jazz songs.

Eleventh Chords

Eleventh chords, like ninth chords, are used mainly for additional color. The extended note doesn’t change the function of the chord (like ninth chords, eleventh chords retain the function of their corresponding seventh chords in a progression; this is due to the inclusion of the characteristic seventh note in each chord).

However, eleventh chords are used much more sparingly in popular music than ninth chord thanks to a few key reasons. The major and minor forms of the eleventh chord, while not cliche, are commonly recognized in jazz songs. The dominant eleventh is a particularly unusual chord.

Few artists use the dominant eleventh without any modifications thanks to its inherent dissonance — the inclusion of the fourth in the chord creates a natural instability. In addition, the interval between the chordal third and the fourth (eleventh) note creates a direct “rub.”

It’s hard to avoid these sharp sounds unless you play your dominant eleventh chords without including the chordal third. If you like the combination of the dominant seventh and the eleventh note, omitting the third can be a good idea to preserve that tone. This tactic is particularly common for harmonizing a melody that includes an eleventh note.

Dominant eleventh chords are used, however, to extend the V chord in a major key. Because of the V chord’s strong pull to the root, the extra dissonance doesn’t alter its character as much as it does with other chords. The seventh note is also a common addition to V chords anyway — especially in the 12-bar blues and jazz — so a dissonant sound is somewhat expected.

Altered V chords like the dominant eleventh are often used within the structure of a ii-V-I progression. The V chord tends to create the tone for the entire sequence by setting up the resolution to the tonic; altering the V chord, therefore, can color the whole sequence with just a few well-placed notes.

Minor eleventh chords are more common than dominant eleventh chords because the minor eleventh lowers the chordal third by a half step to create a minor third interval. This, in turn, adds a bit of breathing room between the minor third and the eleventh note and removes the half-step “rub” found in dominant eleventh chords.

Guitarists looking for extensions for the ii chord in major keys often turn to a minor eleventh chord. Adding the eleventh extension to a ii chord is a tried-and-true tactic to spice up the sound of a supertonic chord, particularly as the opening sound in a ii-V-I progression. In minor keys, the minor eleventh is a common extension for iv chords, resolving back to the tonic.

Instead of lowering the third, other eleventh chords remove the half-step dissonance by altering the eleventh note itself. Sharp eleventh chords are a very common extension for seventh chords; they offer all of the moodiness and spice of a classic eleventh chord without the unpleasant grating. The seventh note is written out in these chords when they’re notated to avoid confusion between the chord root itself and the sharp sign preceding the eleventh (e.g. C# with an 11th versus C #11th). In the key of C major, a C sharp eleventh chord would be notated as C7#11.

Extended chords can add a different dimension to harmony playing; they’re great for accompanying melodies in your songwriting.

Thirteenth Chords

Thirteenth chords are the highest extension possible on guitar. Accordingly, they can provide the spaciest, most wide-open sound of all extended chords. They’re commonly used to modify dominant chords at the high point in a tonal sequence, though their versatile nature makes them a great fit for many different applications.

Technically speaking, a proper 13th chord includes seven notes: the root, third, fifth, seventh, ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth. With only six strings (and four fingers) available to guitarists to play chords, 13th chords on guitar always feature one or more notes dropped from the lineup.

The ninth and eleventh are often omitted, which contributes to the more airy sound of the 13th chord when compared to the tight, clustered structure of the 9th chord and internally dissonant 11th. This is another reason the 13th and its associated permutations have eclipsed the 11th and certain forms of the 9th chord in popularity.

Thirteenth chords can also be used effectively in blues progressions, especially in jazz. Ninth chords would be a more traditional choice to modify classic delta blues tonicized seventh chords; 13th chords offer a smokier, more laid-back feel in comparison to the more angular and punchy ninth. Within blues guitar, 13th chords can modify each chord or simply highlight the changes — the choice is up to you.

Major 13th chords are even less bluesy than dominant 13th voicings because they remove the flat seventh note found everywhere in the blues. Maj13 chords retain some function of a seventh chord, but they provide more space and color than dissonance; you can think of them as flashier maj7 chords in most cases. They’re particularly well-tailored to modify the tonic chord at the end of ii-V-I progressions, as they resolve most of the tension found in the previous two chords without creating a stale, completely vanilla ending to the sequence.

Minor 13th chords, like m11 chords, circumvent the dissonance problems of the eleventh note extension by lowering the third note by a half step. This creates a major ninth interval between the third and the eleventh, alleviating some of the dissonance and providing a much more palatable tone overall. Many m13 chord voicings actually include the 11th note for this reason.

Some lead sheets and composers utilize minor sixth chords (notated as m6 or min6) rather than min13 chords. If you see a min6 chord pop up, don’t panic! The min6 is actually just a min13 with the extended note lowered by an octave. Minor sixth chords are deployed in a similar fashion to min13 chords in most cases; the difference simply amounts to a change in fingering and notation rather than sound.

Extending Seventh Chords in ii-V-I sequences

The most common use of extended chords by far is to alter the tonal character of a seventh chord. Adding the extension creates a more traditionally “jazzy” feel while playing upon the strong desire for resolution to the root that seventh chords naturally create.This method is especially popular with the dominant seventh chords found in the middle of many common jazz ii-V-I sequences.

The dominant chord, notated as the “V” chord since it corresponds to the fifth degree of the scale, strongly prompts a resolution to the tonic, or “I” chord. Dominant seventh chords increase that tension by lending an off-balance, uncertain feeling to the dominant chord.

Extended chords, meanwhile, are generally thought of as adding more harmonic color to the sound of dominant chords. They can also increase the tension by introducing new dissonant intervals into the chord, but many extended chords serve to imbue the chord with a different feeling rather than to just add extra dissonance.

The dominant chord in a ii-V-I sequence is often thought of as the harmonic fulcrum of the progression, merging a minor chord (the second, or “supertonic” chord) with a major chord (the tonic). Tacking extensions onto that dominant chord can change the character of the entire three-chord sequence.

Because ii-V-I progressions are such a common feature in jazz, many jazz guitarists can easily pick out the sound of a ii-V-I progression, and already know how to improvise fluently over the sequence. In fact, so many jazz standards feature ii-V-I progressions that some jazz guitarists grow bored when playing over them again and again.

Extended chords provide new notes for guitarists to focus on when improvising and offer an opportunity to create tastier, more experimental solo lines over what would otherwise be a standard set of changes.

Playing an extended note (say, the ninth or eleventh of a chord) over a standard seventh chord would sound “out” and could create unwanted dissonance in many situations. Including those extended notes in the chord, however, provides an underlying basis to use them in your improvisational ideas and switches up the monotony of stock progressions.

Basic Extended Chord Voicings

9th Chords

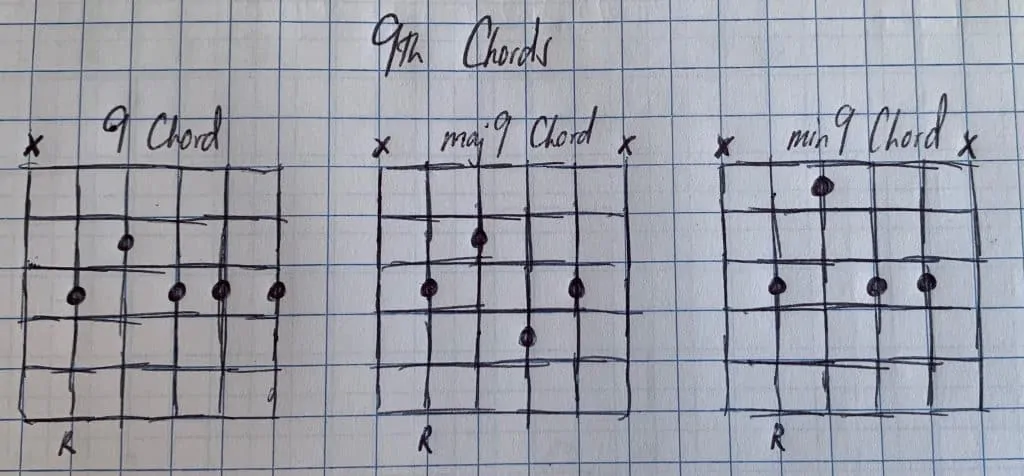

Ninth chords are generally very easy to play. Dominant ninth chords are the most simple; fifth-string root voicings of dominant ninth chords have nearly all of their notes on the same fret without the need for a tricky barre chord voicing.

Minor ninth chords just shift one note (the third) down by a fret from the dominant ninth shape to move from the major third found in the dominant ninth to the minor third interval that builds the minor ninth chord. Maj9 chords simply move the seventh up one fret to change the flat seventh found in dominant ninth chords to a major seventh interval corresponding to the major tonality of the new chord.

Diagram showing the most common voicing for a dominant 9th chord, maj9 chord, and min9 chord. Ninth chords are overwhelmingly played with the root on the fifth string.

Check out the diagram above for some common voicings of ninth chords from a fifth string root — by far the most common way to play them in most songs.

11th Chords

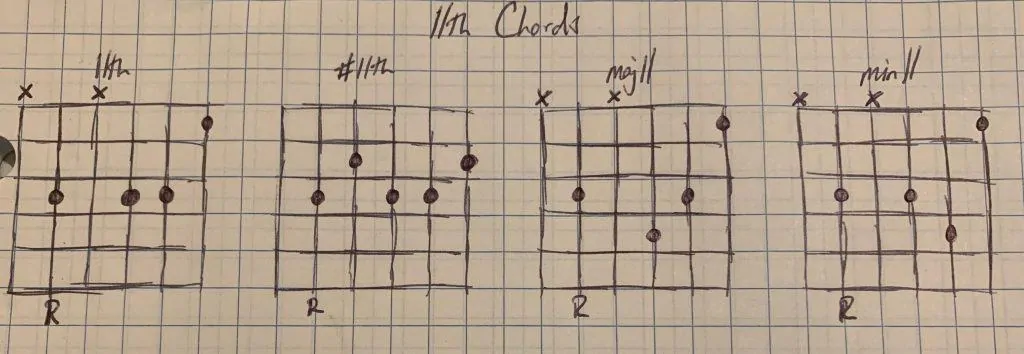

Eleventh chords, like ninth chords, are generally voiced with the root on the fifth fret. Their general structure is relatively simple, and can be played with a barre and just one extra note. Some guitarists will also invert the chord to position the eleventh note at the top of the voicing (on the first string).

Most guitarists choose to tuck their first finger back to play the high eleventh note on the first string, leaving their second, third, and fourth fingers to cover the other notes in the line. Playing this alternate voicing eliminates the need for a bar with your finger, but does require you to mute the fourth string between your second and third fingers. To do this, tilt your fingers down slightly towards the fretboard as you play to lightly dampen the string.

Extending the tip of your third finger over the string to stop it from vibrating can also work; you just need to be careful that you don’t accidentally bar the note and cause it to ring out. This non-barre voicing is more ambiguous between dominant and minor tonality, as it eliminates the third and fifth from the voicing — the major third found in the dominant would separate it from a min11 chord, which instead utilizes a minor third.

Omitting the major third in the dominant eleventh chord also removes the main source of dissonance in the chord structure. However, you can still play the third and avoid the rub by raising the eleventh a half step to form a sharp eleventh chord (notated, for example, as a C#11).

Turning a standard dominant eleventh chord into a #11 chord just entails moving your first finger up by one fret on the top string. The third, meanwhile, is played on the fourth string — instead of muting it, play the note one fret below your other fingers, as you would with a standard ninth chord. In some ways, raising the eleventh makes the chord much easier to play; you can simply bar across the third and sharp eleventh notes and play the root, flat seventh, and ninth with your other fingers.

Major eleventh chords are rare — like dominant eleventh chords, the major third creates dissonance with the eleventh note — but they can be voiced the same way as a dominant eleventh chord with one change. A major eleventh chord incorporates a major seventh, different from the flat seventh that a dominant chord uses. To reflect this adjustment, raise the seventh note by a half step (slide your finger up one fret on the third string).

Different voicings of 11th chords, including a dominant 11th, #11, maj11, and min11 chord. The roots are all on the fifth string for these voicings.

When guitarists want a maj11 sound without the harsh side effects, they generally look to use maj7add4 or maj9add4 chords instead. These voicings counteract some of the dissonance that plagues maj11 chords while retaining a similar character.

Just as you can raise the eleventh note to a #11 in order to voice a dominant eleventh chord with the third note included, you can also adjust maj11 chords to a maj#11 to remove the dissonance. The third note remains unchanged from the structure of the dominant chord; just fret the third note and raise the eleventh up a half step (one fret up on the first string).

Finally, minor eleventh chords are the most common version of eleventh chords found in jazz, blues, and pop. These can be voiced similarly to maj11 chords, except with the position of the fingers on the second and third strings reversed. It’s important to note that while in a maj11 chord these two strings represent the ninth and seventh notes respectively, in a min11 chord they’re the flat seventh and flat (minor) third.

While it would be possible to create a minor sharp eleventh chord by raising the eleventh note a half step once again, the classic min11 chord voicing already includes the minor third, which obviates the need to play the third note on the fourth string.

Min11 chords can also be played easily with the root on the sixth string. In this case, the root, b7, and b3 notes form a line across the sixth, fourth, and third strings (the fifth string is muted), while you can reach back to play the 11th two frets below on the second string.

As with the dominant eleventh voicings, tilt your second finger, which should fret the root note on the sixth string, slightly downward toward the fretboard when you play this chord to properly dampen the fifth string. If you can successfully get your third finger to press into the fifth string without accidentally barring it, you may be able to use that technique as well.

13th Chords

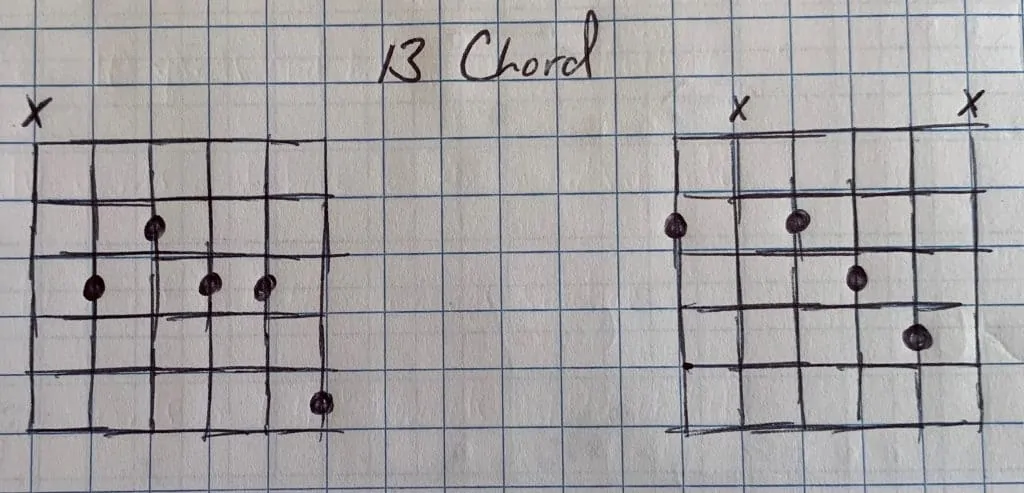

Thirteenth chords incorporate the highest possible extension, the thirteenth note. Technically speaking, traditional extended 13th chords include the 9th and 11th notes as well as the non-extended notes. On guitar, it’s exceedingly difficult to voice 13th chords with all of the notes included at once; the other extended notes are usually dropped to make room for voicings with more reasonable fingerings.

Some 13th chords retain the 9th, but the 11th note is rare to find in a 13th chord, particularly in maj13 voicings — the dissonance created by the close relationship between the two notes turns many guitarists away from the sound.

A good rule of thumb when learning how to play 13th chords on your instrument: take the root and 5th notes of any seventh chord — a dominant, major, or minor seventh will do — and raise each one by one whole step (two frets) to create a corresponding 13th chord. Moving the two notes up will change them from the root and fifth of the seventh chord to the 9th and 13th notes of the new 13th chord voicing, respectively. In the end, this forms a 13th chord voiced with the major third, flat seventh, ninth, and thirteenth notes.

The most common voicings for dominant 13th chords can be found with the root on the fifth string. In many aspects, these are played the same way as a dominant 9th chord from the same root — just raise the note on the first string two frets from its position in line in the dominant 9th chord for the new 13th sound.

Jazz guitarists will also often play dominant 13th chords from the root on the sixth string, by muting the fifth string and incorporating other notes up the neck without the need for a bar. This does force you to mute the fifth string with your fingers as you play the rest of the notes; make sure you can consistently prevent the open string from ringing out before you attempt to play this voicing.

Two popular voicings of the dominant 13th chord. The first has the root on the fifth string, while the second has the root on the sixth string.

Check out the diagram above for two of the most common 13th chord voicings, one with the root on the fifth string and the other with the root on the sixth string.

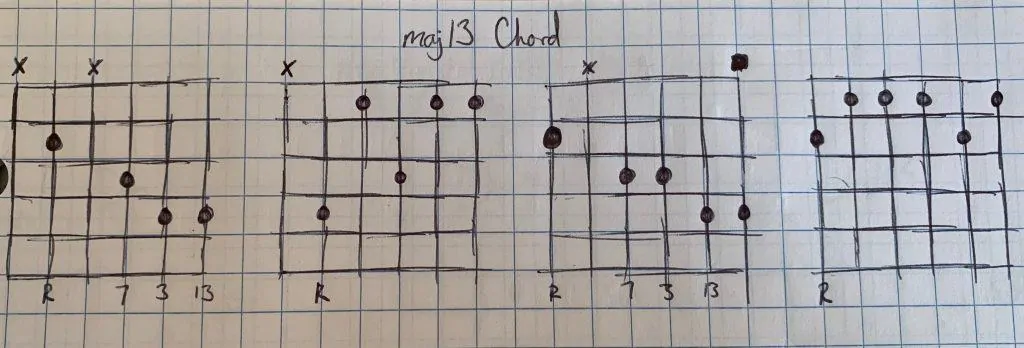

Major thirteenth and minor thirteenth chords are also popular extensions for conveying the luscious, spacey sound of the thirteenth in a more suitable manner for different chord progressions. These chords follow similar patterns as other extended voicings in terms of their fingering and shapes, though there are a couple key differences.

Major 13th chords copy the same general style of dominant 13th chords with the substitution of the major seventh interval for the dominant’s flat seventh. A few interchangeable voicings dominate maj13 chords with the roots on both the fifth and sixth string.

Chart showing four common voicings of maj13 chords. Note how the first voicing with the fifth-string root is similar to the first voicing with the sixth-string root; both include the root, 7th, 3rd, and 13th notes in ascending order.

The chart above contains four of the most common voicings for the maj13 chord, with two voicings including the root on the fifth string and two placing it on the sixth string. Notice the similarity between the first voicing with the fifth string root and the first sixth-string root voicing — the shape is nearly the same for both voicings; the sixth-string root voicing just places the second and third fingers next to each other. Otherwise, the same shape is just moved over one string and an extra note is tacked on at the end of the sixth-string root form.

Minor thirteenth chords mimic their minor ninth cousins in terms of fingering, particularly in voices with the roots on the fifth string. To change a min9 chord to a min13, move the note on the first string up a whole step (two frets). This shape can be tough to nail thanks to the total four-fret span — it helps to have flexible fingers!

If you can’t nail that shape, especially in faster chord progressions, try using a voicing with the root on the sixth string. The most common shape follows the pattern of a m11 chord with an added note lower on the first string. That shape requires your thumb to hold down the root on the sixth string; it’s a great fit if you like to play Hendrix-style barre chords with your thumb up over the neck of the guitar.

Otherwise, you can modify the structure of a classic dominant 13th chord by sliding your third finger down a half step and flattening your fourth finger across the top two strings. That voicing, like the other two m13 chord voicings just discussed, is featured in the diagram below.

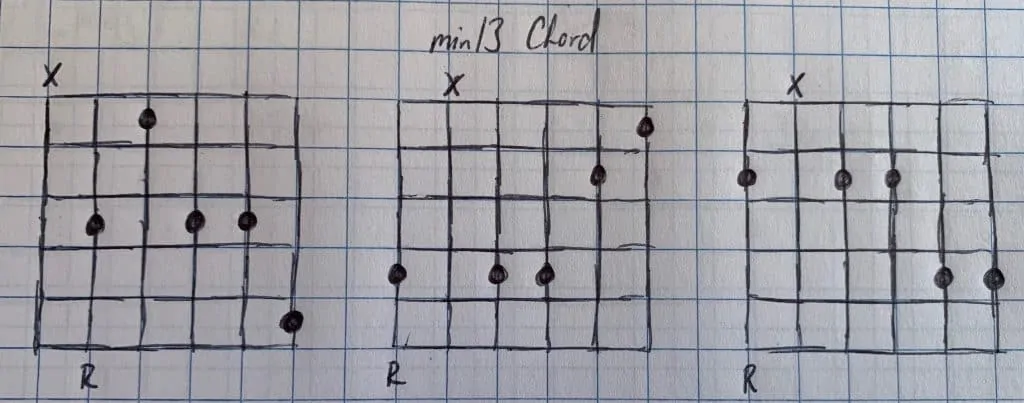

Three most common voicings of the min13 chord. The first one has the root on the fifth string, while the second and third both feature it on the sixth string.

If you want to construct a min6 chord for a slightly different take on the min13 sound, just start with a min7 chord and lower the b7 note by a half step (one fret). This changes the note to a sixth while preserving the shared notes between the two chords.

Incorporating Extended Chords Into Your Playing

Playing Rhythm With Extended Chords

Extended chords are widely underutilized in rhythm playing, whether you’re holding down rhythm on a cover song or composing your own tunes. Some of this underutilization is due to the widespread image of extended chords being “jazz chords” — oftentimes players don’t ever consider learning how to use extended chords.

Yet some extended chords have a long and common history within more popular forms of music. Whether you’re looking to add a slight change to your rhythm playing while sticking with a relatively familiar sound or want some edgy, oddball chords to completely rework your song progressions, extended chords are a great technique to learn.

“Familiar” Extended Chords

They may change the sound of a chord, but many extended chords maintain the same harmonic function as seventh chords — creating dissonance to fuel an eventual resolution to a consonant tonic chord.

Shorter extended chords tend to be more common in popular music than their brethren higher up the ladder. Take the dominant ninth chord, for example, which is found in songs by pop artists like the Beatles, rock bands like Led Zeppelin, and funk groups like James Brown and Wild Cherry.

Early Beatles rocker “Twist and Shout” famously ends with a bang — on a rousing D9 chord. “Play That Funky Music,” meanwhile, takes an E9 chord as the tonic throughout the song and prominently features the D9 chord in the pre-chorus. Led Zeppelin’s “Rain Song” and James Brown’s “I Feel Good” are some other great examples of songs that use dominant ninth chords.

Ninth chords create a deliciously thick sound that’s loaded with rich harmonics. One great benefit of these chords is that they can be swapped out for seventh chords practically at will — the addition of the ninth note doesn’t affect their function in a progression and preserves the classically unstable “seventh” sound.

When changing progressions which use seventh chords to instead include ninth chords, pay attention to the characteristics of each underlying note and use the correct version of each chord. For example, you should substitute a maj7 chord for a maj9, a m7 for a m9, and a dominant seventh for a dominant ninth chord.

If you’re not sure how to select the right one, take a look at the note underneath that chord and its position in the scale. The tonic (I) chord and subdominant (IV) chord, for example, are both major chords, while the supertonic (ii) is minor and the dominant (V) chord is, well, dominant. Each note in the scale of your song’s particular key will carry one of these designations.

The ease of playing ninth chords, as explained above, is another factor that has helped fuel their rise to popularity. Considering how conveniently they slide under the fingers and how easy it is to transition from ninth chords to other chords in the same key, ninth chords are a great set of “bridge” chords for you to get comfortable with extended chords if you don’t normally use them in your playing.

To begin integrating ninth chords into rhythm parts you play, you could substitute them for the corresponding seventh chords whenever those crop up. You could also write songs using seventh chords specifically to provide a template you can later modify with different extended chords.

Ninth chords (and extended chords in general, really) also work great as a loud, ringing chord played to grab an audience’s attention. Just like in “Twist and Shout,” you could carve out space in your songs for striking ringing extended chords. The unconventional harmonic flavor is sure to captivate any listeners, though the underlying harmonic function is easy to incorporate within the confines of more traditional song structures.

11th and 13th chords are more unusual than 9th chords; they create strong jazzy dissonance in your progressions.

Exotic Extended Chords

Ninth chords are by far the most common extended chords used in popular music genres, thanks to their similar tonality to the ubiquitous seventh chord and distinctly dissonant yet familiar sound. Eleventh and 13th chords, however, are much less common. Incorporating these structures into your playing is a quick shortcut to fill your progressions with trippy and exotic sounds.

11th and 13th chords, despite the extra notes, still generally follow the seventh chord in terms of functional harmony. The extra sound doesn’t disturb the fundamental tension inherent in a seventh chord, fueled by the infamous tritone interval between two of these notes (namely the third and seventh).

“Add” extended chords remove the tritone tension by including only the three notes of the major triad in addition to the extended note: the root, third, and fifth. These types of chords give the same extended “flavor” as traditional extended chords without the tension and dissonance.

For those reasons, add chords are more popular for progressions based nearly entirely around extended chords or for spacier, more ambient jams where excess tension for a chord to resolve would feel out of place.

And though extended chords are commonly found on their own, jazz musicians will often combine two or more extended notes to form more complex extended chords, like a Gb9#11.

These chords are even thicker and more sharply angular than classic extended voicings, though the notes themselves are often altered slightly (for example, lowering the ninth by a half step and raising the eleventh in the chord above) to reduce unwanted half-step “rubs” or other dissonance within the chord structure.

Chords with multiple extensions like these are classically found within the context of a ii-V-I chord progression, where they’re used to add color to a rather cliche sequence. This is also true for extended chords that include notes within the first octave, like a Cm11b5 or a Cm6/9.

It is important, however, to make sure that you ground your choices of extended chords in the melody you’re harmonizing. Don’t just pick the craziest extended chord you can think of because you’ve never heard anything like it before. Mapping out your song’s melody beforehand will help you avoid nasty dissonance between your melody and harmony when you add the chords underneath.

Voice Leading

The technique of structuring a song’s harmony around its melody is often referred to as “voice leading.” This is possibly the most important strategy to learn if you choose to use extended chords in your playing, especially the less common eleventh and thirteenth chords.

Just as you create a melody to move your listener from one place to another, your chord progressions should shift over the course of a song from one idea to another. Harmonies that don’t “go anywhere” and just circle around aimlessly generally sound flimsy; a poorly conceived harmony part can ruin a song’s pulse, even if it has a strong melody.

To voice-lead effectively, pay attention to the direction of your melody. Does it go up or down in pitch? Does it change moods — say, from happy to sad, or from worried to peaceful? Your harmony needs to reflect the same moods, or else you risk confusing your listeners and losing their interest.

The simplest way to create an effective harmony part is to analyze the pitches of your melody and make sure each chord in your harmony incorporates the note playing above it. While this technique is certainly a bit more on-the-nose than some others — it’s hard to generate real melodic ambiguity or intrigue when every melody note is spelled out in the chord underneath it — but it’s a good start to help beginners voice-lead properly without struggling.

You’ll also need to make sure that none of the notes in your chord clash with the notes in your melody. Certain intervals can sound incredibly dissonant when played at the same time, like tritone intervals. Unless you’re aiming for a sharp, raw feeling in your song, try to eliminate this dissonance to preserve a harmonious progression.

Some extended chords contain dissonant notes within their own structures before you even add any melody on top. As discussed above, dominant 11th chords can sound highly dissonant thanks to the odd interval created with the added fourth note. Stay away from chords like these if you want to avoid dissonance in your harmony.

Before you use 11th chords in your playing, make sure that the harsher sound won’t impact the mood or feeling of your song. As with all chords, you should also check that no notes in the harmony interfere with the melody.

However, that dissonance can be a positive if you need to create extra tension at a certain point in your song. That intentionally nasty sound could be a unique idea for a punk rock or grunge guitar tune. If you can work it into a tasteful overall composition, go ahead and embrace the rub.

Chordal soloing incorporating the notes of extended chords can be an interesting and unique style.

Soloing Over Extended Chords

If you need to solo over an extended chord, find the voicing of that chord that you’d play for rhythm purposes and pick out the specific extended note. Then, create your ideas in that same area of the fretboard and highlight that extended note over the chord.

This takes some getting used to, and many guitarists struggle to avoid just playing scales up and down the fretboard with a few extended notes included here and there. The key is knowing how to structure your ideas into succinct phrases that listeners can easily digest. This is especially important with extended chords, as you’ll be playing notes that are far more rare than other notes in a certain chord.

You can create effective phrases highlighting those extended notes in a few different ways. The first, and one of the most popular, is to intentionally target those notes at the beginning or end of your improvised lines.

Using these notes to start and finish your melodic ideas is a great way to make sure your audience recognizes the unique tonality of the extended chord. Some listeners, especially those unfamiliar with jazz, may struggle to keep up when listening to fast improvisation and may simply tune out. If nothing else, they’re most likely to remember the beginnings and endings of your phrases.

On the other hand, playing stale, bland lines over stock jazz chord progressions is a great way to get more serious listeners and professional musicians to tune out. Emphasizing the more intriguing notes first will keep their attention locked on you through your whole solo line.

From an aesthetic perspective, leading with the more out-there notes also gives your playing a unique flair. Rather than taking the “safe” route and sticking to basic modal techniques or simply playing one scale for your whole solo, outlining the characteristics of each extended chord by focusing on their extension notes immediately distinguishes your ideas from the proverbial “pack.”

Blues and rock players are often used to ending their lines with neat resolutions to “home notes” like the root of a chord; they also tend to start their ideas on major beats and maintain strong ties to the underlying rhythm of the song as they solo.

Extended notes lack the tonic quality of the root — in fact, they’re inherently more unstable and off-kilter than the other notes found in garden-variety major chords. Ending your lines on extended notes, therefore, will sound odd or unfinished to many guitarists who typically just play styles like blues and rock.

Changing the rhythm of your phrases can alleviate this problem. Landing on an extended chord and wrapping up your line on an offbeat part of a measure sounds much better than coming to a dramatic stop at the end of your solo with a squeaky, unresolved extension. Adopt a more jazzy aesthetic when you solo to work in extended chords more effectively. Don’t be afraid to start and finish your phrases at unexpected times, and play behind the backbeat to create a looser, slinkier feel.

If you’d prefer to retain your same rhythmic style but still want to use extended notes, consider working them into other parts of your phrases. To borrow an old jazz phrase, repetition legitimizes — using extended notes as part of repeated rhythmic figures like triplets and motifs is a great way to harness the power of extended notes to color your solo without distorting your rhythm or timefeel.

Extended chords are an accessible way to incorporate more theory into your playing style.

Summary

Extended chords may seem like a useless piece of knowledge, something you’ll learn but never actually use. And while they may not be as common as power chords or classic barre chords, extended chords provide a spacey, dissonant sound that’s unlike any other chord.

Incorporate extended chords into your playing style and your songwriting to see the results firsthand. Chances are you’ll find they’re a lot more common than you first thought!