At BeginnerGuitarHQ, it’s our mission to teach you how to play the guitar as well as possible. One of the most important parts of a guitarist’s toolbox is the humble scale. You’ve probably become rather used to standard major and minor scales, but were you aware of the different types of minor scales that can completely change your composition and playing?

In this important guide, I’ll be explaining how you can use the Harmonic Minor Scale within your guitar playing.

If you’re on the lookout for a way to spice up your melodies, chords and improvisation look no further than this useful guide.

First Things First

What Is A Scale?

The most important first thing to be aware of when approaching the Harmonic Minor Scale, is what a scale actually is. In general, a scale is simply a series of notes arranged by pitch. In general, scales can be ascending or descending, and mean the same thing either way (though we’ll look at the melodic minor scale in a future guide, as this one changes when ascending and descending). Many scales are just the notes of a key organised into a row. For example, the D Major key is made up of the notes D, E, F#, G, A, B and C#, so the D Major scale is simply these notes arranged in ascending/descending order.

While we’ll use the word ‘scale’ throughout this guide, remember that by all intents and purposes, the word is effectively a synonym for ‘key’. They don’t mean the same thing, but for basic understanding, you don’t need to worry about the nuances.

There Are A Lot Of Scales

Today, we’re looking at the Harmonic Minor Scale (which we’ll get to in a moment) but there are hundreds more scales in existence. One way to look at scales is to imagine a piano. The white notes from C-C make a simple C major scale. Move up to D, and if you simply go from D-D without hitting a black note, you’ll be playing the Dorian mode. A mode can be referred to as a scale when organised, but doesn’t have the same ability to be considered a ‘key’.

The important thing to remember when considering scales is that they can be transposed with ease. For example, a C major scale is built on a set of distinctive intervals that can be lifted and placed elsewhere to create a D major scale. Similarly, a D Dorian mode can be reduced to its intervals and moved anywhere to create the Dorian mode on any other note.

What Is A Minor Scale?

A minor scale is any scale (well, almost any, but don’t worry about that right now) scale that has a minor third. The natural minor scale, also known as the Aeolian mode, is made up of the white notes from A-A on a piano. The melodic minor scale is much more complex, as it is exactly the same as the natural minor scale when descending, but has a raised sixth and seventh on the way up. This would mean that the A melodic minor scale would be a simple A-B-C-D-E-F-G on the way down, but would have an F# and a G# when ascending.

And What Is The Harmonic Minor Scale?

The Harmonic Minor Scale is slightly different from a major scale, a natural minor scale and a mode, as it doesn’t natural exist in terms of the piano white notes. This means key signatures don’t lend themselves to its existence, as they have a raised seventh which introduces the all-important augmented second interval and creates a leading tone. For ease, we’ll refer to the C Harmonic Minor scale throughout this guide.

The most important notes in the C Harmonic Minor Scale are:

- C. Of course, the first note we have to pay attention to is the tonic. This is the first note of the scale, and assuming you’re using it in the way it is intended, the note which would feel ‘final’. For example, the conclusion of a melody in the C Harmonic Minor scale should feel complete when it lands on C.

- Eb. This is the note that proves that we are using a minor scale. The minor third gives a dark sound to the scale which wouldn’t be there is this was an E natural. The tonic chord of C minor is therefore made up of C, Eb and G.

- Ab. The Ab note furthers the flattened darkness of the Harmonic Minor Scale, but it isn’t particularly distinctive on its own. However, in conjunction with the next note, it forms the most distinctive part of the scale.

- B. The B natural at the very end of the harmonic scale gives the scale its distinctive tone. Firstly, the Ab to B jump creates an interval that doesn’t appear in any naturally occurring scales. It also means your dominant chord is a major chord, and it creates a leading tone that leads directly into the C tonic.

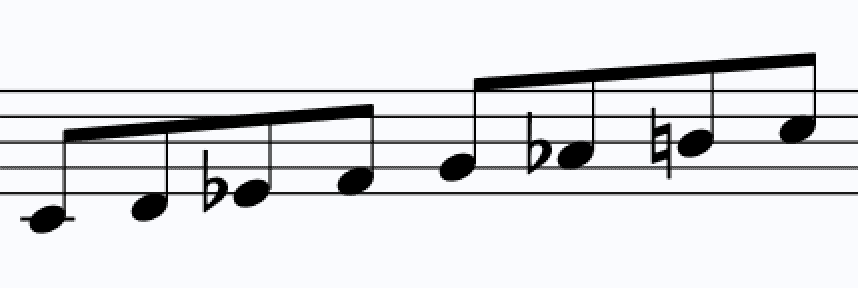

So remember: C, D, Eb, F, G, Ab, B.

The harmonic minor scale on C

Transposing The Harmonic Minor Scale

Moving The Harmonic Minor Scale

While we’re referring primarily to the C Harmonic Minor scale, any note can have its own harmonic minor scale made up of the same intervals and therefore having roughly the same tonal feel.

The easiest (but longest) way to do this is to simply look at the notes, and move every single one of them up by the amount necessary to reach the new tonic. For example, if you’re starting on C and want to play the Eb Harmonic minor, then you need to move every note up by a minor 3rd. Take the C and move to an Eb, the D and move to an Eb, the Eb and move to a Gb… Keep going until you’re in the new correct place.

The second way, which is quicker but a little more complex, is the preferred method which will benefit your theoretical understanding of the scale as well as your use of it. You’ll need to remember the interval pattern of the Harmonic Minor Scale:

Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Semitone, Augmented Second, Semitone.

The harmonic minor scale on A

Now you can use this anywhere you want. To create the G Harmonic Minor Scale, for example, start with that movement of a tone that takes you from G to A. Then move by a semitone to the minor 3rd of Bb. Two tones then take you through C and D, before a semitone movement brings you to Eb. The augmented second movement comes next, taking you to an F# (a move of major second would take you to F, so simply sharpen it), and then finish the scale with a semitone that ends up at the G tonic.

Apply this same logic to any note you may need to use, and you have a basic understanding of how to form the Harmonic Minor Scale anywhere you want, and can start to use it in melodies.

Using The Harmonic Minor Scale In Melody

The harmonic minor scale sort of sounds a bit like it can’t be used in a melodic context. It’s not only called the ‘harmonic’ scale, but there is a different scale in existence called the ‘melodic’. Despite these misleading names, remember that you can use it whenever you want and end up with a distinctive and interesting sound as a result.

Avoid: Making The Minor Sixth Sound Strange

The minor sixth is always a strange part of a scale. It’s arguably the ‘weakest’ note in a minor scale, and also one of the easiest to change between its major and minor forms, so there are certain times when it might just sound a little weird, even when diatonic to a harmonic minor scale.

Jumping from D to Ab, for example, is a jump of a tritone, which is often considered the most dissonant interval in music. Similarly, a G to an Ab is a semitone; the other most dissonant interval. Of course, using this potentially jarring movement for effect will work perfectly, but if you’re going for a specifically consonant sound, then be careful with where you put your minor sixth.

Do: Make Us Of Its Darkness

The harmonic minor, despite having a major chord V, is a dark, minor key. It has a minor 3rd and a minor 6th, with two tritone intervals buried within and a creepy leading tone/augmented 2nd combination. This makes creepiness and negativity its middle name.

If you’re using the mode harmonically then the point isn’t quite as prominent, but using the harmonic minor to form melodies provides an incredible wealth of unsettling sounds. You can of course use the minor 3rd as you would in any other scale, but you can also combine it with some of those dissonant intervals we mentioned above, and some of the unique sounds that are created by two of the important intervals mentioned below.

Do: Make Use Of The Leading Note

The leading note is probably the most important thing about the harmonic minor scale as it is what separates it from other minor scales. It gives you a lot of options to make your melodies way more interesting than sticking to the natural minor.

Firstly, the leading tone can be used to create something unexpected. In a minor melody, the listener is set up for certain expectations; in general, these expectations would link directly to the natural minor. Raising the seventh creates something they wouldn’t expect, which therefore already makes your melody more memorable.

It also helps lead into your tonic with much more ease. The natural minor scale, technically, has exactly the same notes as a simply major scale a minor 3rd higher. So the A minor scale is made up of the same notes as C major, and so the two can in certain situations end up blurred. There is no ‘normal’ scale made up of white notes and a single G#, like the A Harmonic minor. The fact that the leading note is present helps you keep thing very distinctively centered on the A tonic, and using it in melodies will allow you to rise towards the tonic with incredible clarity.

Use the leading note in a melody

Do: Make Use Of The Augmented Second Interval

If the leading tone is the most distinctive feature of the harmonic minor scale, then the augmented second is the second most distinctive. Technically, this interval is made up of the same distance as in a minor 3rd, but context changes it hugely. For example, the leap between F and Ab is a minor 3rd: expected, not at all dissonant. A change of context to the A harmonic minor scale means this interval is now an unexpected, strangely dissonant F to G# movement. The pitches are identical, but their context gives a completely different sound.

The fact that the harmonic minor scale gives you the ability to explore this incredibly unique sound means you should use it to your advantage. There isn’t a single scale or mode based on the piano white notes that includes an augmented second interval naturally, so if you’re using the harmonic minor, make this one of the reasons why.

Do: Use It In Classical Music

As you’ll find out, the harmonic minor scale isn’t typically used in popular music to create melodies. This isn’t to say it is avoided across all facets of popular music entirely, but thanks to its very distinctive sound and the challenges of accurately singing an augmented second, it tends to be left by the wayside in favor of modes and the natural minor.

However, it is rife within classical music written for guitar (and just about any other set of instruments). Of course, as the 20th Century progressed, standard tonality was pushed further and further away, but the latter part of the 18th and the mid-19th century would draw on the harmonic minor a huge amount in order to create truly dramatic, emotive melody lines. If you’re writing or playing classical music, then this use of this scale will more than likely help you to further authenticate your sound.

Avoid: Creating Clashes With The Two Tritone Intervals

As mentioned above, there are two tritone intervals in the harmonic minor scale. This isn’t revolutionary: there is one in the sickly sweet, positive major scale as well. However, the subtle layer of dissonances added here by the presence of two tritones (between the second and the minor sixth, and the fourth and the raised seventh) creates something even more prone to dissonance.

Therefore, when using this scale to create melodies, you need to be constantly aware of the fact that you could accidentally be moving from tritone to tritone and creating a jarring move that (most of the time) doesn’t sound quite right.

Using The Harmonic Minor Scale In Harmony

The thing the harmonic minor scale got its name from was its use in harmony. It only changes one note from the natural minor, but it has a huge impact on the sound of the chords you can create as a result. We’ve come up with four ways you can use the scale to your advantage in your harmony.

Avoid: Creating Unwanted Dissonances

The tritones mentioned above can also create problems in your harmony as well as your melodies. Through the natural minor scale, you don’t have to worry about a dissonant chord VII: in C minor, this is made up of the notes Bb, D and F. In the harmonic minor, this becomes B, D and F, which is a highly dissonant diminished chord.

Things get even more complex when you bring the seventh into play. The natural minor version of chord VII7, is a dominant 7th. Dissonant, yes, but very common in most popular music. When you add the seventh to a diminished chord in this context you end up with B, D, F and Ab. This is a diminished seventh chord, which is arguably the most dissonant chord you can make using ‘traditional’ harmony.

Do: Use The Major Chord V

Like the leading tone in a melody, it is the major version of chord V that defines harmonic minor harmony. Playing chord in a minor key are typically associated with sadness and negativity, but they certainly don’t have to be.

Depending on the context, the major chord V can take you either side of this division. Using the harmonic minor in a bouncy, positive way can be enhanced by the use of a major chord that you’d normally expect to be minor. Contrastingly, the sudden use of major version of an expected minor chord can add a feeling of eerie positivity to a chord sequence.

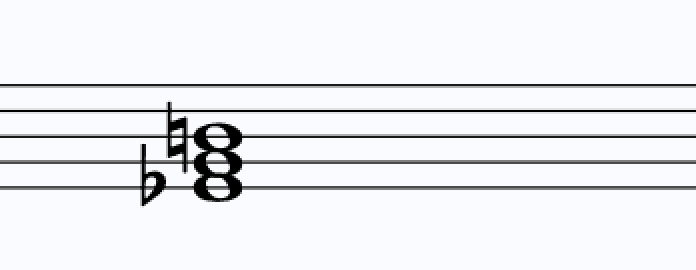

Use the major version of chord V

Do: Use Chord Seven

As mentioned above, the diminished version of chord seven and the diminished seventh it therefore causes are two hugely dissonant chords that can really take away the impact of a chord sequence if used by accident or in the wrong place.

Having said that, they can have an incredible effect on your music when placed well. A moment of tension can be heightened hugely by a very dissonant chord, while a moment of resolution can be lifted to a new level if a hugely dissonant chord is placed before it.

One particularly powerful harmonic minor cadence places a chord (G, B, D, F, Ab) before a C minor tonic chord. This puts dissonances of a tritone, various sevenths and a minor ninth all together before each falling into place to return to the tonic chord. When used well, this level of dissonance can have a huge impact.

Do: Use The Augmented Chord III

Another of those tell-tale chord is the augmented version of chord III. Augmented chords very rarely appear naturally in tonal music and have a distinctive sound. Chord III is one of the lesser used chords even in a major scale, so the augmented interval created by the raised seventh gives an even more unexpected sound.

Thanks to its strange nature, you’ll have to be careful when working it into your music, but in certain situations, it can sound great. Try moving from the augmented chord III back to the tonic, with the augmented fifth acting like a leading note.

Use the augmented chord III

Do: Use It To Modulate

While key changes in popular music are often abrupt an unprepared, there is no stronger way to change key than to place a dominant seventh chord a fifth above the new tonic. For example, in C minor, creating a perfect cadence from G7 down to Cm will confirm your tonal centre perfectly. Now, borrowing a chord from the harmonic minor version of your target key will have the same effect.

If you want to move from C minor to G minor, for example, then finding a place to work a D7 into the mix (D, F#, G, C) will help you to move straight down to your new tonic on G below, thanks to this very strong perfect cadence.

Avoid: Maintaining The Raised Seventh For No Reason

Despite all of the claims above stating how to best use the harmonic minor scale, there is one key piece of advice that should stay with you throughout all of your uses of the scale. If you want to use the harmonic minor scale but the raised seventh doesn’t sound right in a chord (or a melody line for that matter), then just don’t use it.

You’re free to move between a variety of keys and modes to create whatever sounds the way you to want it to. Just because you’re in the harmonic minor at one moment doesn’t mean you need to stay there forever.

Examples Of The Harmonic Minor Scale In Use

- Schubert- Death And The Maiden Quartet. As mentioned above, the harmonic minor is found much more frequently in classical music than in popular music. This Schubert quartet ticks the main boxes for the use of the harmonic minor: dramatic, emotive, powerful. It might not be written for guitar, but there are certainly guitar arrangements that would allow you to get a grasp on how best to use the scale.

- Opeth- Master’s Apprentice. There are a multitude of Opeth songs that use the harmonic minor scale (and many that use even darker ones) but we settled on ‘Master’s Apprentice’ as it shows it off on acoustic and heavily overdriven electric guitars. This demonstrates how the scale can be used for delicate, highly melodic phrases just as easily as crunchy, intentionally dark and dissonant moments of heaviness.

- Yngwie Malmsteen- Far Beyond The Sun. Bridging the gap between the use of the harmonic minor in metal music and in classical music is Yngwie Malmsteen. He is a neo-classical guitarist who takes classical compositional ideas, brings them to a metal band and pumps them with distortion. As such, ‘Far Beyond The Sun’ and many of his other tracks use the harmonic minor mode a lot. As you can hear, even with the backing band present, just that one raised seventh changes the character so much and makes you understand why it doesn’t appear in popular music very often.

Scales Related To The Harmonic Minor Scale

- Harmonic Major Scale. As you can guess from its name, the harmonic major scale is the major equivalent of the harmonic minor. The only difference between the two is that the major version has a major third instead of a minor. Alternatively, you could look at it as a major scale with the sixth lowered. Remember above when I mentioned the sixth being the most interchangeable part of most scales? Well, this one proves that, by allowing the Ab to be the only black note (if looking at a piano) in the major scale. This creates a diminished version of chord bVI and a diminished chord II, as well as a variety of other interesting harmonic implications. The leading note and augmented second are still very much present, though.

- Double Harmonic Scale. The double harmonic scale gets its name from the duo of augmented intervals found within. You could view it in a variety of ways: a harmonic major scale with a flattened second; a harmonic minor scale with the flattened 3rd moved to the 2nd; or a Phrygian scale with a raised third and seventh. The two augmented intervals and opening minor second mean this scale has a sound very unfamiliar to Western listeners, but its use in Indian and Arabic music (under different names) is quite common.

- Melodic Minor Scale. The melodic minor scale is something I referenced at the very start of this guide. When played ascending, the sixth and seventh degrees are raised. This creates a similarity to the harmonic minor (the raised seventh) but a huge difference, due to the removal of the leading note and the augmented second interval. On the way back down, it simply becomes the same as the natural minor, removing the raised seventh connection, but reinstating the flattened sixth.

Conclusion

The Harmonic Minor Scale is so distinctive in sound that it is easy to pick up on whenever it is used. As a result, however, it is often avoided in popular music in favour of more subtle scales and appears much more often in the classical world. Despite this, it can add real flair to music played in just about any style, so don’t shy away from it. The three main things to take away from the existence of the scale are:

- Use the incredibly harmonic variety to your advantage. With the ability to introduce an unexpected major chord into your work, or dramatic dissonances you wouldn’t have access to in any other scale, or an augmented third chord, you should be making sure to use these interesting chords where possible.

- Make the most of the leading tone. That leading tone is the difference between a complex, notable and unique scale, and a basic natural minor. It can help you change or confirm a key, add a bit of spice to a melody, or simply lighten up a potentially dark phrase.

- However, don’t stick to the harmonic minor if it isn’t creating the sound you want. Just because you started out by using that scale doesn’t mean you have to stay with it the whole time. If moving to a different scale gives you the note you want, then do it: no one is stopping you. Probably.