Sooner or later, all new guitarists face the same dilemma when it comes to their strings.

Maybe you’ve noticed some rust building up. Maybe they don’t stay in tune like they used to. Maybe they have a dull, dead sound. Or maybe they’re unravelling around your headstock. These are all telltale signs that it’s time to say sayonara to your old strings and swap them for new ones.

But how do you know which types to go for? Most music stores have a literal wall-to-wall display behind the counter. Not to mention the hundreds of types you can find online…

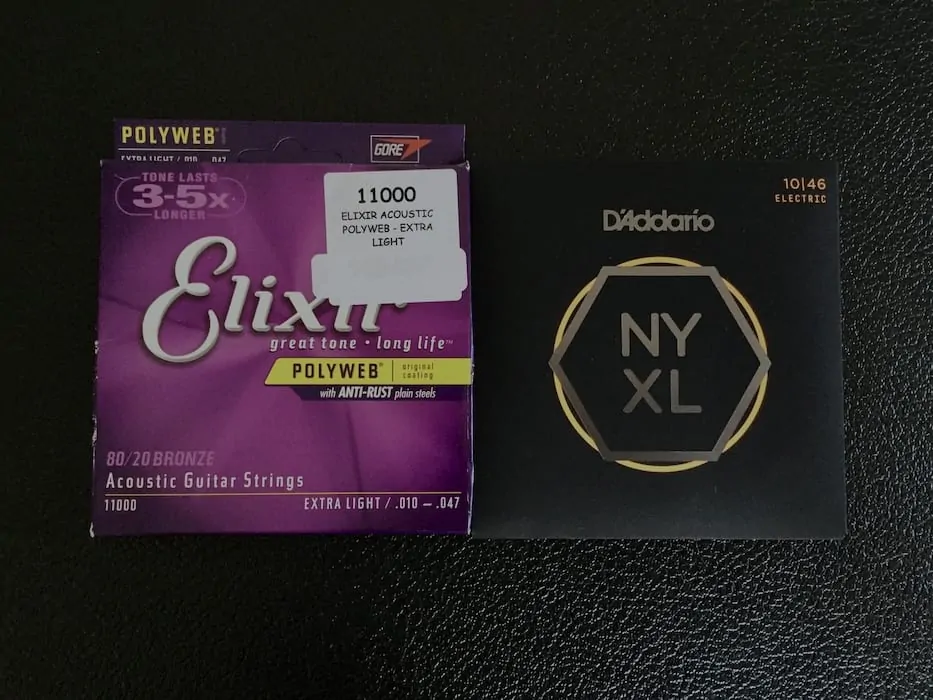

Elixir polyweb custom lights? D’Addario flat top phosphor bronzes? DR Sunbeam Acoustic Round Cores? The options are endless!

Sorting through all of these technical terms may seem intimidating. But don’t fret (bad pun, I know). Once you know what to look for, you can cut through the choice overload and find the right ones for your guitar.

Contents

Basic Factors

No matter what type of guitar you have, there are some basic things to consider before you choose your strings.

Ultimately, you want ones with the best sound (and feel) for your style of playing – whether it’s shredtastic metal or sweet fingerstyle folk. Different brands have different finishing touches that make their products unique. Still, these six factors should give you a rough idea of what to look for…

Gauge

Gauge is just a fancy term for thickness. It’s hard to believe, but even a thousandth of an inch can make a huge difference in your guitar’s sound and feel. After all, going up just one gauge can increase the overall tension up to 20%!

The 1st string (high E) on your guitar is always the thinnest, so it can reach those high treble notes. The 6th string (low E) is the thickest, so it can give you low bass notes. The other strings fall in between these two extremes, with the 5th (A) being the 2nd thickest, the 4th (D) being the 3rd thickest, and so on.

The most common gauges for steel-string acoustics and electrics are:

- Extra/super light: .010-.047 for acoustic, .009-.042 for electric

- Light: .012-.054, .010-.046

- Medium: .013-.056, .011-.050

- Heavy: .014-.059, .012-.054

Many players refer to gauges by the thickness of the 1st string. So, if someone says they have 10s on their electric, this means that they’re using a light gauge.

Some brands offer extra heavy electric or even lighter acoustic gauges, starting at .009 or .008. They’re easy to break though, so heavy strummers steer clear of them. Other brands have hybrid options like custom lights (in between extra and regular lights), medium-lights or medium-heavies. The hybrid types usually have the lighter gauge for the 1st-3rd strings and the heavier one for the 4th-6th strings.

For classical guitars, nylon strings sometimes use the same gauges as standard acoustics. But it’s more common to find them classified by tension. The three main types are:

- Low: also called moderate or light

- Medium: also called normal

- High: also called hard or heavy

No matter what type of guitar you have, there’s pros and cons with each gauge. Higher gauges create more tension. This boosts your volume, reduces fret buzz and produces notes with a warm, mid-heavy tone and lots of body. These strings are also sturdier. This means you’ll be less likely to break one in the middle of a gig or practice session.

But the thicker your strings are, the less lively they’ll sound. They’ll have a strong attack (initial burst of sound), but shorter sustain. You’ll lose the intricacies of legatos, because it’s harder to fret and bend your notes. This can be a challenge for beginners especially. And on fragile guitars, heavy strings can warp or break the neck and bridge.

Generally, lighter gauges are better for:

- Small-bodied acoustics (ex: parlors, grand concerts, auditoriums)

- Shorter scale lengths (the distance from the nut to the bridge)

- Beginners or returning players with no calluses

- Fingerpicking

- Standard tuning

- Lead guitar

- Vintage instruments

- Genres like folk, country and melodic rock

Medium and heavy gauges are better for:

- Large-bodied acoustics (ex: dreadnoughts, jumbos)

- Longer scale lengths

- Experienced players

- Strumming and slide playing

- Drop tunings

- Rhythm guitar

- Low action guitars

- Genres like jazz, punk and acoustic rock

Core

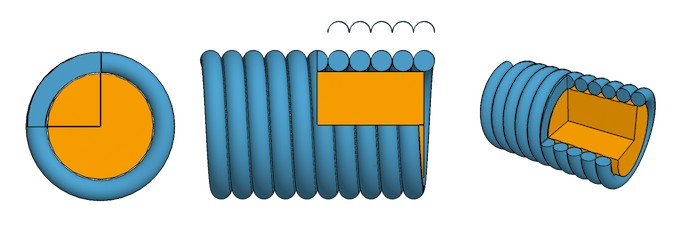

As you probably guessed, the core is the shape of the wire under the 6th, 5th, 4th and sometimes the 3rd string. The two types of cores look identical from the outside. But there’s a world of difference in their sounds – especially when you add distortion.

Round cores were the original design. They hug the outer wrap wire all the way around, with no gaps. This gives you a flexible feel, mellow tone and long sustain – making round cores a favorite for classic rock, rockabilly and blues players.

Unfortunately, round cores are pretty high maintenance. They tend to break and go out of tune on a whim. Plus, you have to tune them to pitch before trimming the ends. Otherwise, the outer wrapping will unravel.

Needless to say, a lot of guitarists find round cores a pain in the you-know-what. That’s why most strings today are made with hex cores.

Because they grip the wire wrap at six contact points, hex cores are more stable than round cores. They’re a bit on the stiff side, but produce a bright, treble-heavy tone with a strong attack. This makes them the go-to types for alt rock, metal and other modern genres.

Still, there’s nothing quite as nostalgic as the sound of round cores. So, if you want that vintage tone, you can find a handful of brands that manufacture them for acoustics and/or electrics.

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/n0XimR_-rV0″ frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

This video compares round core GHS Boomers to hex core D’Addario XLs. Other than their cores, their compositions are identical.

Winding

When we talk about winding, we’re referring to the way the wire wrap is wound around the core. The easiest way to tell the difference is to look at the surface of your string.

Roundwounds have a textured surface. They have a bright tone and flexible feel, making them a solid choice for rock, metal and fingerstyle. The steel-core acoustic and electric types are a bit on the noisy side. But many classical roundwounds are polished to flatten the top and reduce any finger squeaks.

A cross section of a roundwound string (“Diagram of roundwound strings for music instruments” by GreyCat / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Roundwounds are also the cheapest and most widespread option. However, they need to be replaced more often than the other two types.

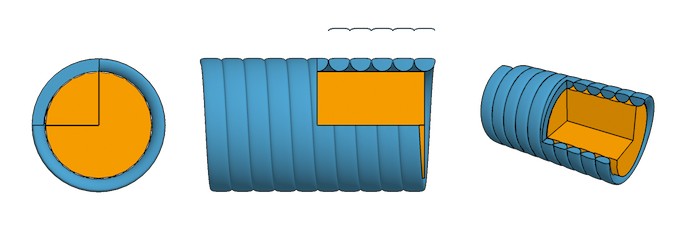

Like the name suggests, flatwounds have a flattened surface. They produce more tension on the fretboard, which means less fret buzz and smoother note transitions. But they’re harder to fret and have a dark, bass-heavy tone.

A cross section of a flatwound string (“Diagram of flatwound strings for music instruments” by GreyCat / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Because of this, flatwounds are the universal choice for bassists. You can also find them on jazz and blues instruments – especially semi-hollow electrics. They’ve been known to make an appearance in bluegrass circles too.

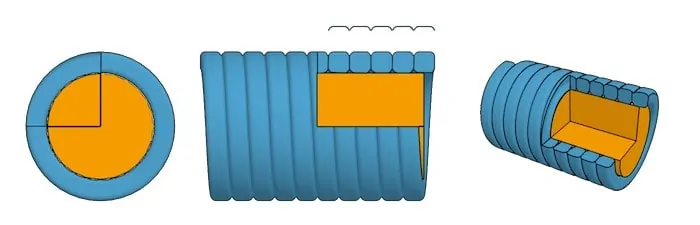

Half rounds have a slightly flattened surface. They’re brighter than flatwounds, but stiffer and darker sounding than roundwounds. They’re also the most expensive of the three types and may be hard to find at your local store.

A cross section of a half round string (“Diagram of halfwound strings for music instruments” by GreyCat / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Still, if flatwounds aren’t your cup of tea, then half rounds are your best bet for comping and flatpicking.

Coating

In the late 90s, Elixir revolutionized the industry by launching coated guitar strings. With a plastic polymer around the wire wrap, they keep away sweat, dirt and other corroding grossness.

Coated strings last twice as long as uncoated ones. But they’re about twice as expensive. Also, they aren’t as bright and have less sustain. Still, if you’re like me and you tarnish every metal you touch, then it’s worth the investment.

There are two major types of coating, developed by Elixir and copied by other brands:

- Nanoweb: with a light coating, they feel and sound more like uncoated types.

- Polyweb: with a heavy coating, they have a smoother feel and longer lifespan.

Ends

Standard acoustic and electric strings are secured to the bridge with ball ends. Most classical ones have tie ends, which you loop and twist directly over the bridge.

Ball ends on a bass vs. tie ends on a classical guitar

However, you can find a handful of classical types with ball ends. They’re a favorite with folk musicians, as well as beginners who haven’t mastered how to tie their strings.

Material

This is one of the biggest factors affecting the feel and sound of guitar strings. Electrics, acoustics and classicals all use different materials. So, we’ll look at each one individually.

Electric

When you play electric guitar, your sound is affected mostly by your pickups and your amplifier. But the types of strings you use also play a part.

The most common electric guitar strings are made out of steel and/or nickel. There’s a handful of other metals you can find too.

Steel

Steels are the brightest electric types. They have a long sustain, carrying your guitar’s sound above other instruments – even with heavy distortion. They also cut down on your finger squeaks.

Steel is a must-have for modern-sounding genres, like metal, rock and country.

Nickel

When you play with nickel strings, your notes will be warmer, richer and fuller. But you might be drowned out by your jam buddies.

Because of this, nickel is more popular with rhythm guitarists. It’s also typical in vintage-sounding blues or jazz.

Nickel-plated steel

These are the most common types. With a nickel plate on the 4th-6th strings, they give you the best of both worlds – warm, full-bodied bass/mid notes and strong, bright treble notes. They also have a strong attack, placing your instrument front and centre at the gig.

You can find nickel-plated steel in any genre.

Other metals/alloys

Some types are made from special steel alloys (metallic mixes). For example, D’Addario NYXLs are made from a high-carbon steel core. This boosts your sustain and keeps your guitar in tune for longer periods.

Occasionally, you can find ones made from other metals, like:

- Titanium: long-lasting, with a bright tone.

- Cobalt: has a bright tone and wide range.

- Chrome: has a warm tone, but breaks easily.

Some of these metals also come in different alloys. For example, Ernie Ball makes cobalt-iron strings that attract the magnets in your pickups better than other types.

Acoustic

When you play a standard acoustic, most of your tone is determined by how the body of your guitar resonates. But unlike electrics, acoustics have no magnetic pickups. Even acoustic electrics use non-magnetic piezo pickups. This means that the types of strings you choose will have a bigger effect on your overall sound.

All acoustic guitar strings are made from steel cores – hence the name “steel-string acoustic.” The biggest variation comes from the types of metal they have on their outer layers.

The two most widespread acoustic wire wraps are brass and phosphor bronze.

Brass

Until phosphor bronze began to dominate the market in the 70s, brass strings were the go-to for acoustic players. Even today, they’re a favorite for musicians who want to bring out the “natural” tones of their instrument.

Depending on the brand, you may find brass listed as 80/20 bronze. This refers to the fact that it’s an alloy of 80% copper and 20% zinc. Since bronze is actually an alloy of copper and tin, “brass” is the more accurate term.

Brass combines a strong bass on the lower strings with a super bright tone on the higher strings. This can be a disadvantage on parlor guitars, where it can sound thin and tinny. But it provides a nice balance on anything above an orchestra model (OM) or grand auditorium size.

Another word of warning – brass ages faster than other types. Even after a few hours of playing, you may notice that your strings have lost their brilliance. They’re definitely not the best option if you hate changing them regularly. Still, if you take care of them, you can make them last.

Phosphor bronze

Sometimes called 92/8 bronze, these types have a high copper composition, along with some added phosphorus. This makes them warmer and mellower than brass, with more emphasis on the mid range. They’re also corrosion resistant and maintain a constant “new string” sound.

Phosphor bronze sounds equally great in all genres and across small- and large-bodied guitars. It can also make a cheap guitar sound more expensive than it actually is. Some musicians see that as a drawback. But if you’re a budget player, it’s definitely a bonus.

Some brands also offer phosphor bronze with different alloys. For example, D’Addario’s nickel-plated phosphor bronze has a brighter tone that sounds more like new brass.

Silk and steel

Like the name suggests, silk and steel types have a layer of silk between the core and the outer wrapping (usually phosphor bronze) on the 6th-3rd strings. This lowers the tension, giving you a flexible, soft touch that’s easy on the fingertips.

Silk and steels have a warm, delicate tone – almost like a classical guitar. This makes them the ideal types for folk and fingerstyle musicians with a vintage or small-bodied instrument.

Nylon

Steel strings should never go on a classical guitar. Ever! Classical guitars are lightly braced, with a delicate body. You might accidentally snap its neck by using high tension steel.

That being said, you can technically put ball end nylons on a standard acoustic. This was especially popular with folk musicians in the 50s and 60s. But it isn’t something I’d recommend.

Because nylons are low tension, you can expect a lot of fret buzz when you play, unless you adjust your truss rod. Plus, with a super low volume, your sound will probably disappear when you jam with other musicians.

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/ROPzAgn9o_k” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

Check out this video for a demo of nylon strings on a steel-string guitar.

If you really want the warm tone of nylon strings, you’d be better off buying an actual classical guitar. With the right guitar body, you can master a diversity of styles – from flamenco to gypsy jazz to Willie Nelson-style country.

Classical

While classical guitars are often called “nylon string guitars,” this is a misnomer. Nylon may be the most popular material today. But before the 1940s, classical strings were almost entirely made from sheep or cow gut. The 1st-3rd were plain gut, while the 4th-6th were wound in silk thread.

Unless you feel like combing through antique shops for gut, you’ll need to stick with synthetics on your classical.

Nowadays, strings are made of a synthetic material, with the bass ones wrapped in metal.

Because flamenco guitars are built differently than your average classical, it’s better to buy nylons made specifically for flamenco. This will help you capture those quintessential Andalusian tones.

For other genres, any classical string types will do.

Treble/mid

The 1st, 2nd and 3rd (and sometimes the 4th) strings are usually made from one of three types of nylon:

- Clear: the most popular option, made from a monofilament with specific gauges for each string. Clear nylon has a rich, smooth, balanced tone.

- Rectified: these types have an even diameter across the whole length, resulting in a full, mellow tone.

- Black: made from a different kind of nylon, these types have a warmer sound and more treble overtones than clear nylon. They’re a common choice for folk musicians.

Besides nylon, other common materials are:

- Titanium: the only safe metal for classical guitars. They’re bright and smooth, with a long sustain.

- Fluorocarbon: also known as carbon fiber, they stay in tune better than other types. However, they can be sharp sounding, with a strong attack and short sustain.

- Composite: this multifilament is strong, loud and bright. 4th strings are usually composite, creating a seamless transition between your bass and treble notes.

Bass

The 4th, 5th and 6th strings are usually made from a multifilament nylon core and a metal wrap. The two major types are:

- Gold: also called bronze or brass. Like standard acoustics, they’re wrapped in brass. Thanks to their brilliance and long sustain, they’re the top choice for many players.

- Silver: wrapped in silver, these types have a smooth feel and warm tone. They tend to be more common with rhythm guitarists.

Final Thoughts

Now that you have a better idea of the different types of guitar strings available, you can choose the best fit for your instrument and playing style.

And if you’re still undecided? Experiment! Try different gauges, coatings and materials across different brands. You may find the perfect combo in an unexpected place.

Elixir and D’Addario are my go-to brands for both my acoustic and electric. But yours may be entirely different, depending on what you’re looking for.

Once you’ve settled on your strings, the next step is to make them last. Wash your hands before you play. Wipe down your fretboard with a clean, dry cloth after you’re done. Invest in a good string cleaner if you sweat a lot or play in a humid environment.

It’s also a good idea to write down the date you changed your strings on the package. This way, you won’t accidentally show up for a gig with dull, rusty 11s.

Happy strumming!