The key of C is where beginners tend to start, and an excellent place to begin practicing songs. So, why not learn the chords that flow together within the key of C? It only sounds logical, right? As you read on, we will cover what these chords are, and some music theory pertaining to that. Let’s dive in!

Contents

The Key of C

A key can simply be defined as, “a collective group of pitches that form the harmonic foundation, deriving from the tonic”. If that sounded like a lot of gibberish, then let’s break it down:

- The key is determined by the root note, whether that be Ab Major, E minor, or in this case: C Major.

- The key, and whether the key is Major or minor helps us determine our key signature.

- Key signatures may contain a collection of sharps (#) or flats (b) that alter the note. If the note is marked with a sharp, it’s to be raised by a semitone. However, if the note is marked with a flat, it’s to be lowered by a semitone.

In the key of C, we have no sharps and no flats. This makes it an excellent place for beginners to start as you don’t have to worry about altering notes, and can play something that sounds simplistic and pleasant to the ear. Our C Major scale looks like this:

C > D > E > F > G > A > B > C

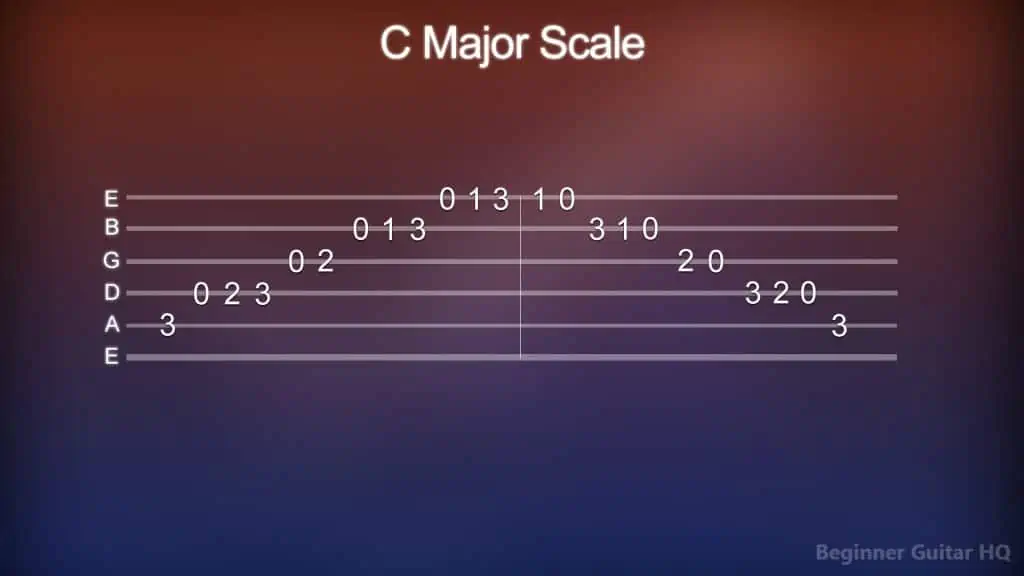

On the guitar, using tablature (tab for short) you may play it like this:

Guitar tablature of the C major scale in a very simplified form.

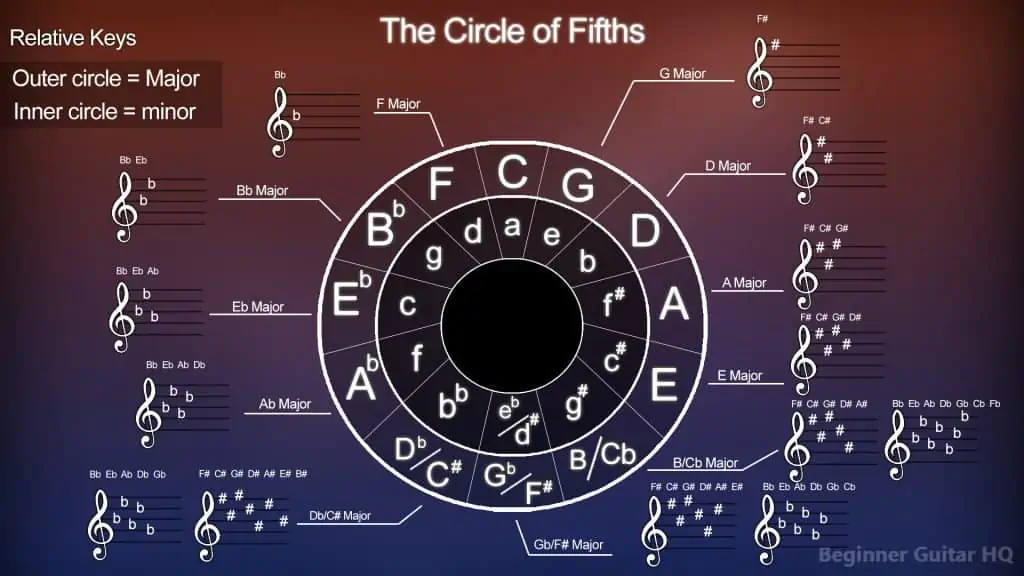

Let’s briefly go over the circle of fifths. The circle of fifths is a “wheel-shaped” diagram that shows all of our most common key signatures in a very easy-to-understand format:

The diagram of the circle of fifths shows the various key signatures in major and minor.

The outer ring of the diagram shows all of the Major keys, while the inner ring shows the relative minor keys (keys that share the same key signatures as the major keys). You will notice that going clockwise starting from C, the keys get an additional sharp, all the way to C# major, containing 7 sharps. But how are these sharps determined by note?

You simply need to know the acronym: FCGDAEB. This stands for:

“Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle”

This is only said for you to remember the acronym, as the first letter of each word represents a note that is to be sharp. As we go clockwise along the ring:

C = No sharps or flats

G = F

D = F, C

A = F, C, G

E = F, C, G, D

B = F, C, G, D, A

F# = F, C, G, D, A, E

C# = F, C, G, D, A, E, B

You’ll see that as you go along the wheel every key gets an additional sharp that follows the sequence of the acronym FCGDAEB. However, the main idea is to remember how many sharps each key has, as well as what the acronym stands for. So if you know B major has five sharps, you may count with your fingers and say, “Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And”, then you know the key of B major has five sharps which are F, C, G, D, and A.

You might have also noticed that C has no sharps or flats, yet C# major contains all 7. The same is true with Cb containing all 7 flats. Anything beyond that gets you into some weird territory of key signatures containing double sharps, and double flats, but we won’t get into that.

Moving forward, the other half of the wheel contains the keys with flats in their key signature. Slightly different than the method of finding the sharp key signatures, we reverse the acronym making it: BEADGCF. This stands for:

“Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’, Father”

The ring going counter-clockwise will also follow this sequence:

C = No sharps or flats

F = B

Bb = B, E

Eb = B, E, A

Ab = B, E, A, D

Db = B, E, A, D, G

Gb = B, E, A, D, G, C

Cb = B, E, A, D, G, C, F

That’s pretty much all there is to it! Of course, knowing this, you will see how C major will have a different key signature than its parallel minor, C minor. This is because C minor has 3 flats, while C major has nothing in its key signature. If you wanted the relative minor to C major, you would get A minor, as it shares the same key signature.

So why is the C major scale important?

Aside from the C major scale being an excellent scale to learn for beginners due to its simplicity, it’s a tried and true staple for a lot of things to make you a better musician. Or at least enough to get you started on that journey!

Learning inversions for the C major triad is very simplistic and gives you a great way to see how they work. If you look at your root position triad for C major, you get C > E > G. When you shift it to the first inversion that now becomes E > G > C. Shifting to the second inversion you get G > C > E. If you were on a piano playing these, you would not have to worry about black keys being part of the inversion, therefore, making it a little easier to practice. However, on guitar, it might get a little more complex, due to the layout of the fretboard. Thankfully, using the same three strings to form the triad and its inversions up the neck isn’t too challenging in C major.

Practicing improvisation on the guitar in the key of C major is a great place to start. Not having to worry about playing any sharp or flat notes and staying within the key is fairly easy. You can simply start up a backing track, and try soloing over it within the C major scale!

An interval is the distance between two pitches and is therefore given their own respective names to represent that distance. Using C as your root note, it gets a lot easier to define these intervals:

C > C = Perfect 1st (Unison)

C > Db = Minor 2nd

C > D = Major 2nd

C > Eb = Minor 3rd

C > E = Major 3rd

C > F = Perfect 4th

C > G = Perfect 5th

C > Ab = Minor 6th

C > A = Major 6th

C > Bb = Minor 7th

C > B = Major 7th

You can play from whatever C note you feel most comfortable on. If you’re on the piano that might be middle C, if you’re on guitar that might be the 3rd fret of the A string, (the first note of the C major scale tab we’ve gone through earlier). You can try this for yourself, playing C, then the next note going up, back to C, and then the next note after, and so on.

The C major scale is used for solfege as well! Solfege is primarily used for singing the C major scale, where every degree of the scale is sung with a different syllable. For instance:

C = Do

D = Re

E = Mi

F = Fa

G = Sol

A = La

B = Ti

C = Do

This is also a great practice for challenging yourself with “sight-singing” as you can jumble up the syllables into a melody and practice singing along to them in the correct pitch.

For beginner pianists “middle C”, also known as C4, is very important for determining what octave you are in, making it an excellent reference point. For those using a full-sized piano, this would be the 4th C note up from the lowest (left-most) C, being C1. For guitar, it’s a little different, as an easy place to find middle C would be on the 1st fret of the B string, or the 5th fret of the G string. Other places include the 10th fret of the D string, the 15th fret of the A string, and the 20th fret of the low E string.

For both guitarists and pianists, however, the C major scale is an excellent place to begin for reading musical notation (sheet music). This is primarily due to the fact that the key signature of C major contains no sharps or flats. For pianists starting out, this is excellent, because that means you don’t need to use the black keys yet. For guitarists, it’s nice because when you’re starting out, the fretboard might look like a jumbled mess, so trying to read notes with sharps or flats could be a little challenging for now.

Chords Within the Key of C

Finding a good chord progression for your song can be challenging. Thankfully, there is a method to make this task much easier! All you need to know is what key you are in, the scale following it, and the key’s respective triad. Let’s go through this in a little more detail:

As we know, the key determines the pitches involved in its scale. This can be done by consulting the circle of fifths. As we already know, however, the key signature of C major has no sharps and no flats. With this information, we can move on.

Our scale is heavily determined by our key signature. In the key of C major, we have the notes:

C > D > E > F > G > A > B > C

Major keys follow the pattern: Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semitone

Every note within our diatonic scale (a seven-note scale containing 5 tones and 2 semitones), has a name specified as a different degree:

C = Tonic (1st Degree)

D = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

E = Mediant (3rd Degree)

F = Subdominant (4th Degree)

G = Dominant (5th Degree)

A = Submediant (6th Degree)

B = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

C = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

Whether you are trying to add tension or bring resolve, all play an important role in how melodies and chord progressions work.

A triad is a collection of three notes played in combination to form a chord. Of course, there are 7th chords, using four notes, 9th chords, using five..etc. Therefore, not all chords are triads. However, in this case, triads are going to help us figure out what chords go with the key of C major!

To form a major triad, you need to stack the 1st degree of the scale, the tonic, the 3rd degree of the scale, the mediant, then the 5th degree of the scale, the dominant. This gives you the triad of notes: C, E, and G. That is a C major triad. If we look at chord progressions within a major key, they always follow this pattern:

“Major, minor, minor, Major, Major, minor, diminished”

When we bring our C major scale into the mix, we get:

- C Major

- D minor

- E minor

- F Major

- G Major

- A minor

- B diminished

To make each of these different chords, we’ll do exactly what we did with the C major triad, but on every degree of our scale:

- 1st degree: C Major – C, E, G

- 2nd degree: D minor – D, F, A

- 3rd degree: E minor – E, G, B

- 4th degree: F Major – F, A, C

- 5th degree: G Major – G, B, D

- 6th degree: A minor – A, C, E

- 7th degree B diminished – B, D, F

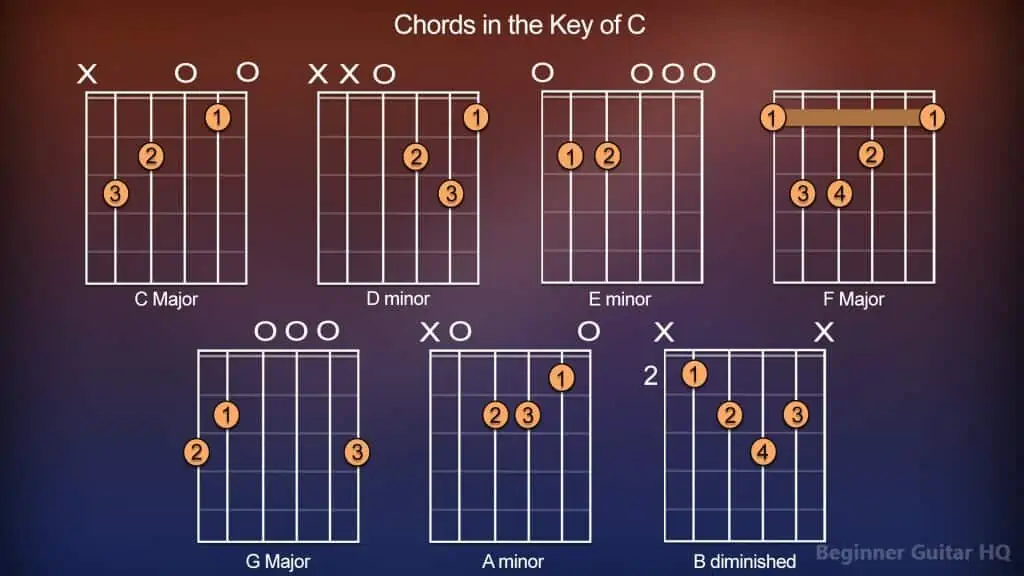

Here are how you play the individual chords within the key of C:

Chord charts of the chords used within the key of C

Now, there are some tried and true chord progressions that you may utilize in your own music. Remember when we mentioned how important the scale degrees are? This is where that comes into play. Each degree serves its own purpose, but we’ll only focus on just a few standard progressions that you can get started with right away:

- (I – IV – V) which becomes: C – F – G

- (I – vi – IV – V) which becomes: C – Am – F – G

- (ii – V – I) which becomes: Dm7 – G7 – C7

The 1st degree, the tonic, is a common starting place for most chord progressions as it’s the root note and the most vital degree of our scale. A common thing to see within chord progressions is for the tonic to jump to the 4th degree, the subdominant, to add some tension. This will often be followed by the transition to the 5th degree, the dominant, which adds even more tension, begging for resolve, which tends to lead back to the tonic again.

In the case of our third chord progression, which gives off a “jazzy vibe” is not that abnormal for it to begin on the 2nd degree, the supertonic. It’s followed by more seventh chords, commonly used in Jazz music, but also acts as a sort of “fill-in” for our 4th degree because of their similarities in notes.

In the case of our sixth degree, the submediant, it’s a nice degree to bridge off into other pre-dominant chords, like our supertonic or subdominant.

Trouble With Chord Charts?

If you are a beginner, here’s a quick rundown of a chord chart. The box you see with all the lines represents the fretboard of the guitar. Every vertical line represents a different string on the guitar. The leftmost is your low E string, followed by A, D, G, B, and then the high E string. The horizontal lines are to separate one fret from the next.

The circles with numbers 1 – 4 inside indicate what finger you need to hold that string down with to complete the chord. Number (1) is for your index finger. Number (2) is for your middle finger. Number (3) is for your ring finger. Finally, number (4) is for your pinky finger.

At the top, you might see an “O” or an “X”. The O represents an “open string” (a string not to be fretted, but still played to complete the chord. Then there’s the X, which represents a string that is not to be played. Last but not least, we may sometimes have a number off to the left next to a fret. This is usually meant to indicate that the starting point to form the chord is somewhere higher on the neck, and the number indicates which fret that is.

That’s all there is to it!

CAGED System

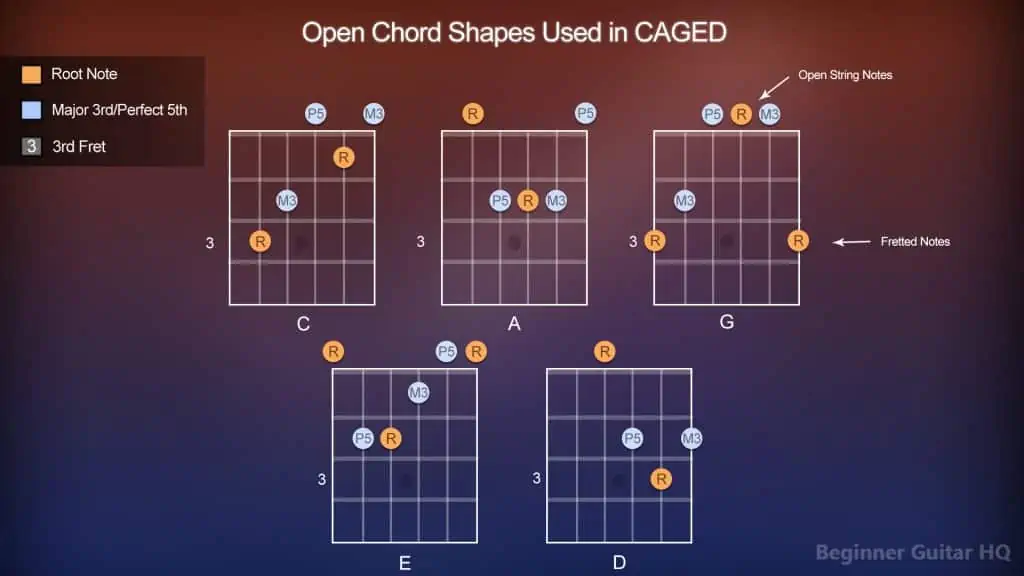

If you’ve ever wanted to not only see but experience the fretboard differently, then using the CAGED system is perfect for you. It’s a really helpful way of seeing the fretboard as more than a jumbled mess of notes, but rather, a series of patterns and chord shapings. It’s all based on these chord shapes:

Chord charts of the CAGED System’s various chord shapings

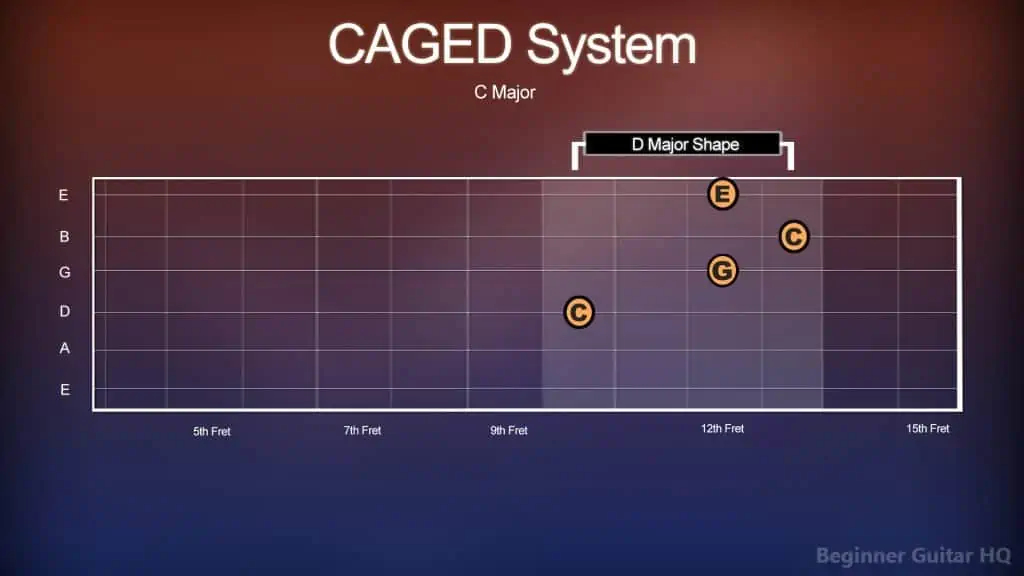

As you have probably noticed, that is exactly where the CAGED system gets its name from. The idea behind the CAGED system is that every chord shape flows into the next! So for instance, the C chord shape would flow into the A chord shape, then the G, E, and D, until it goes all the way up the neck on the 12th fret where we’re back on C again! Here’s an example of it going up the neck using C as our starting point:

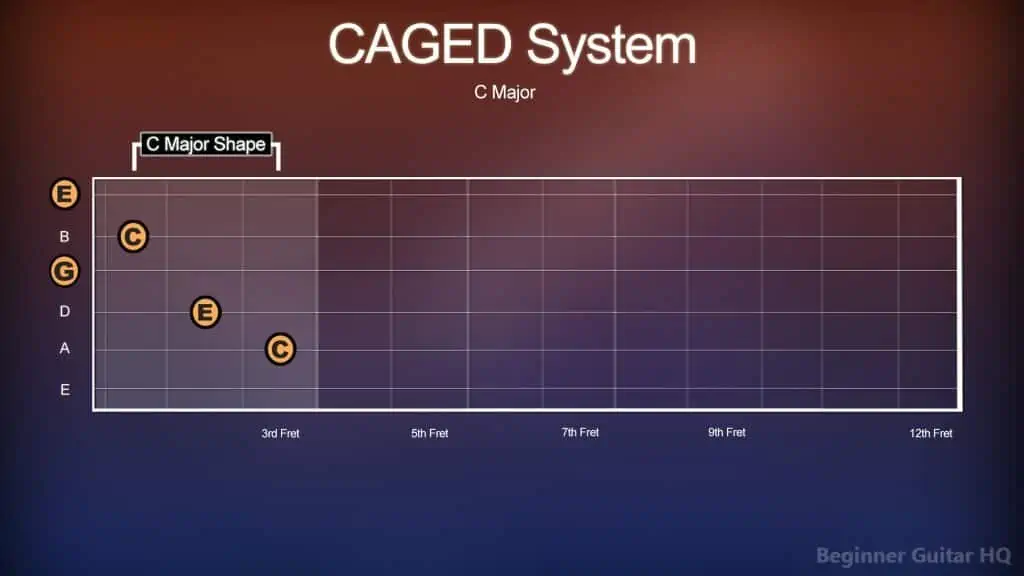

The C Major chord shape in the open note position

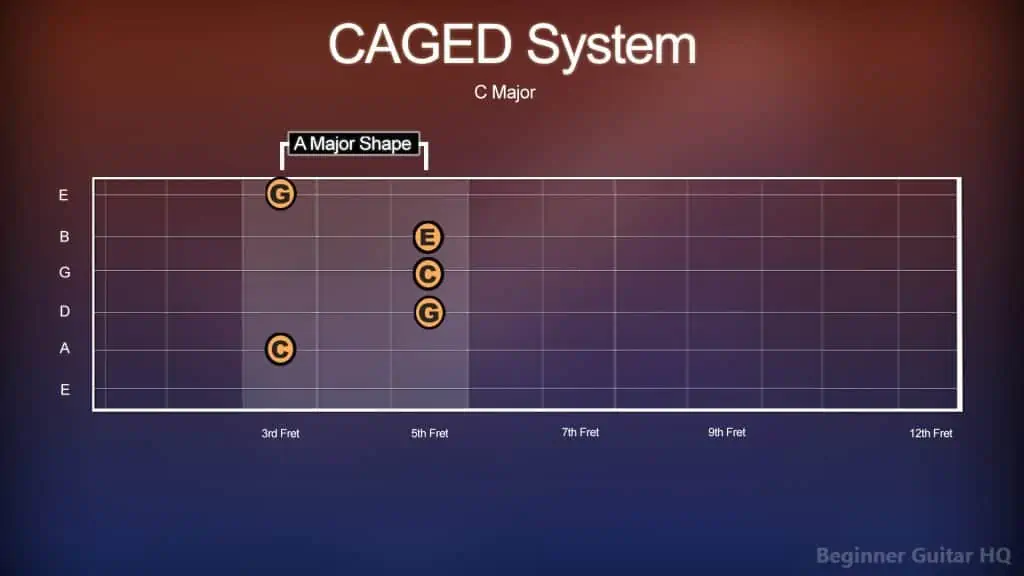

The A Major chord shape on the 3rd fret, but is still a C chord

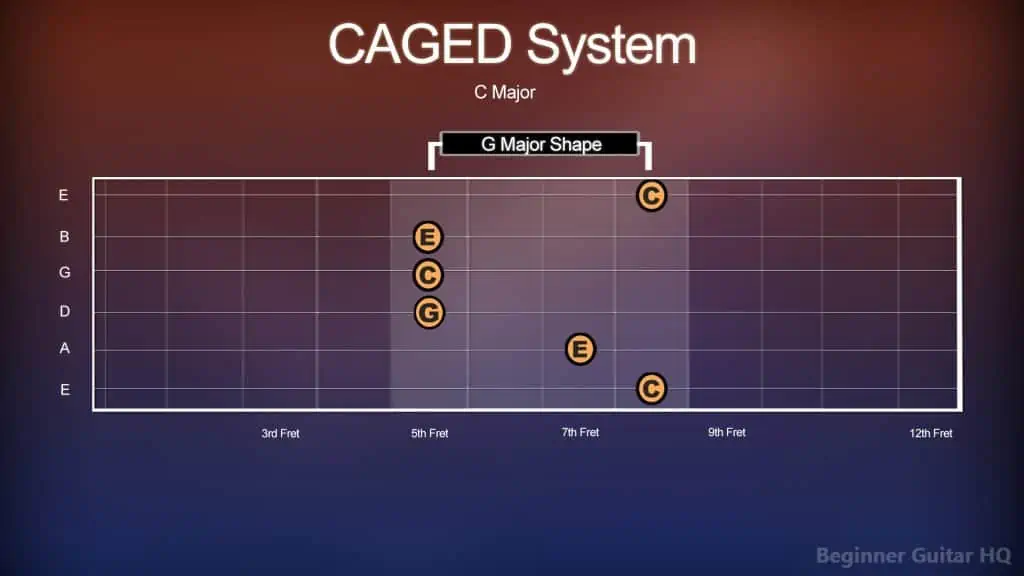

The G Major chord shape on the 5th fret, but is still a C chord

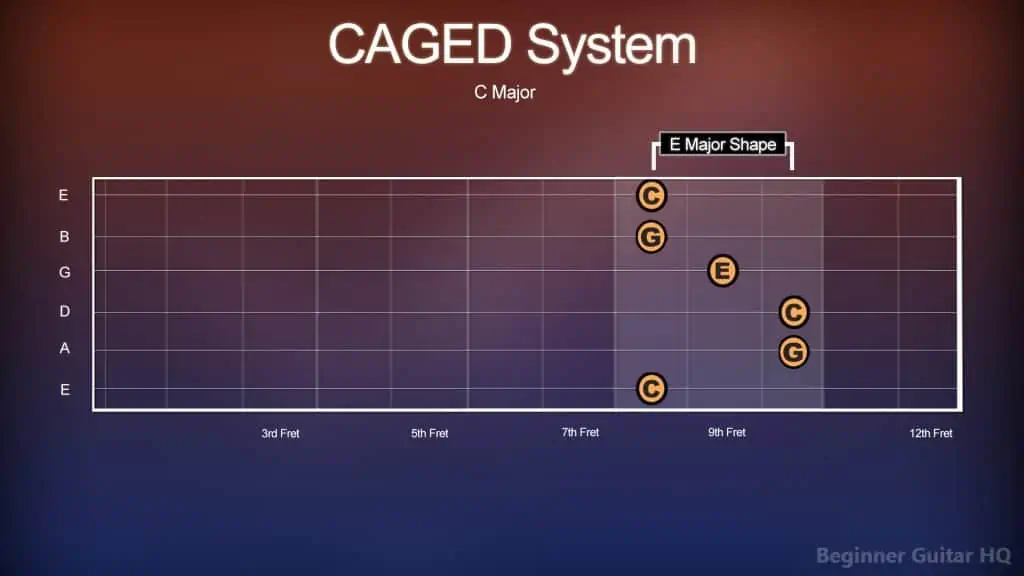

The E Major chord shape on the 8th fret, but is still a C chord

The D Major chord shape on the 10th fret, but is still a C chord

The C Minor Scale

C major shares more similarities with A minor than it does with C minor. Both C major, and A minor when sharp or flat contain all seven sharps and flats. However, C minor contains only three flats, and C# minor only contains four sharps. The only real similarity between C major and C minor is that they share the same tonic.

So, what does the C minor scale look like? Containing three flats, the C minor scale looks like this:

C > D > Eb > F > G > Ab > Bb > C

This, being a minor scale, would also follow its own pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S), making it:

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

You would also get a very different set of triads in the key of C minor:

1st Degree: C minor = C > Eb > G

2nd Degree: D diminished = D > F > Ab

3rd Degree: Eb Major = Eb > G > Bb

4th Degree: F minor = F > Ab > C

5th Degree: G minor = G > Bb > D

6th Degree: Ab Major = Ab > C > Eb

7th Degree: Bb Major = Bb > D > F

Conclusion

Now you can make a bunch of great-sounding chord progressions within the key of C. It doesn’t hurt to experiment and test different degrees on the C major scale to make your own unique progression. On the other hand, using what’s proven and used time and time again can also be a great place to start. As you might have noticed, many pop songs share the same chord progressions. The possibilities, however, are endless!

If you’re new to playing the guitar, remember to take things slow, and let your fingers build up strength over time as you learn to master these chords. Don’t get discouraged if it doesn’t sound perfect. It might even be good to practice along with widely popular songs in the key of C, like “The Beatles – Let it Be”, or “Lynyrd Skynyrd – Simple Man”. You might even want to enter the realm of barre chords, and practice songs like “Tom Petty – Learning to Fly”, or “Creedence Clearwater Revival – Have You Ever Seen the Rain”, as they contain that troublesome “F chord”.

The sky’s the limit, and as long as you’re having fun, that’s all that matters. Keep on rockin’.