Are you looking to expand your chord repertoire on the guitar? Then you’re in luck! The G7 chord is one of the many seventh chords you may learn on the guitar, and more importantly, it’s fairly easy to play! For beginners, this is an excellent chord to get yourself started before learning other seventh chords and their variations. Let’s dive in!

Contents

What are Seventh Chords?

In a nutshell, a seventh chord contains a triad with an interval of a seventh from the root note of the chord. Typically, in modern times, a chord like this would be used within the genres of blues and jazz but isn’t uncommon in the realm of hip-hop, deep house, and neo-soul.

So why should you learn to use seventh chords?

Firstly, they are great for adding more color and feeling to your existing chords, by placing that seventh interval on top. A common way of using a chord like this is by taking the chord on your 5th degree (dominant), and your 7th degree (leading tone), and turning them into seventh chords. This is because those degrees hold the most tension and beg for resolve. Adding a seventh interval to these chords will only increase this tension. However, seventh chords aren’t limited to these degrees and may be used elsewhere.

For beginners, this may give you some further insight into the world of scales and key signatures. It’s one thing to learn how to play the chord, but it’s another to also understand why it works! Of course, there are plenty of successful musicians out there without a lick of knowledge of music theory, like Jimi Hendrix, Elvis Presley, or even Taylor Swift. However, understanding music theory will not hinder you as a musician, but help you build on it.

Finally, chords are an excellent way of building up finger strength and muscle memory. Using tried and true chord progressions is something many artists do, however, to take yourself to the next level, you may want to consider branching out. This means trying different and perhaps more challenging chords, and what better place to start than with seventh chords?

How to Play the G7 Chord

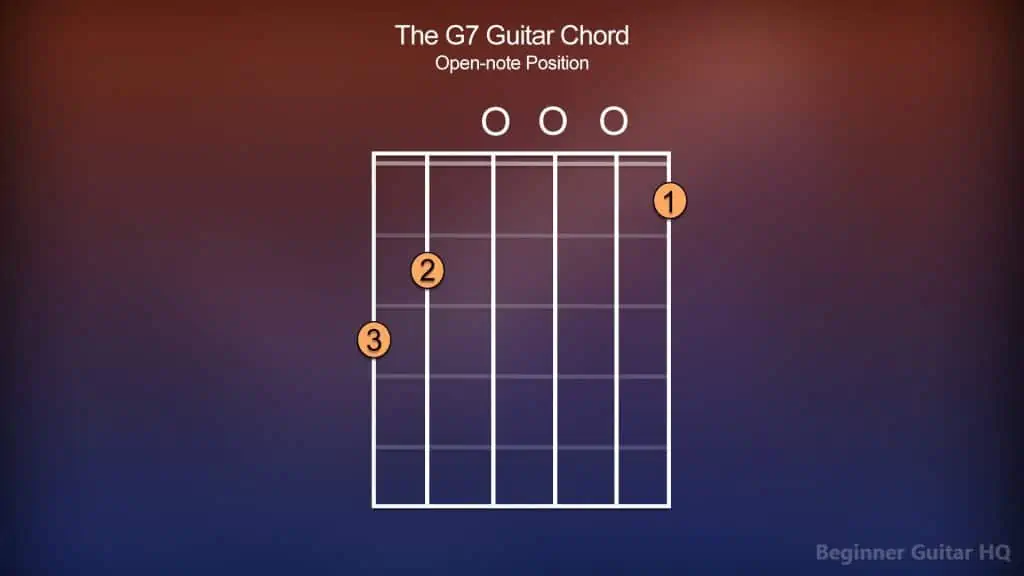

The G7 Chord is not that different than the G Major chord. The main thing that you need to worry about changing is your fingering, which shouldn’t be too difficult. Here is how you play the G7 chord from the open-note position:

Chord chart of the G7 guitar chord in open note position.

Chord charts:

If you’re a beginner, seeing a chord chart for the first time might be a little intimidating. Fortunately, they’re very simple to understand! Let’s run through it!

The box you see before you represents the fretboard. The six vertical lines from left to right represent the six strings on the guitar, low E, A, D, G, B, and then the high E string. The horizontal lines are what separate one fret from the next.

Next, you’ll notice that there are numbers 1 – 4 inside of circles within the frets. These numbers represent the fingers used on the fret to complete the chord. The number 1 is for your index finger. The number 2 is for your middle finger. The number 3 is for your ring finger. Finally, the number 4 is for your pinky finger.

You may also notice above the fretboard there’s an “O” or an “X”. The O represents an “open note”, a string to be played but not fretted. The X represents a string that is not to be played to complete the chord. Finally, a number may sometimes be present to the left of the fretboard, which indicates the starting fret for the chord to be played.

It’s easy as that!

G Major

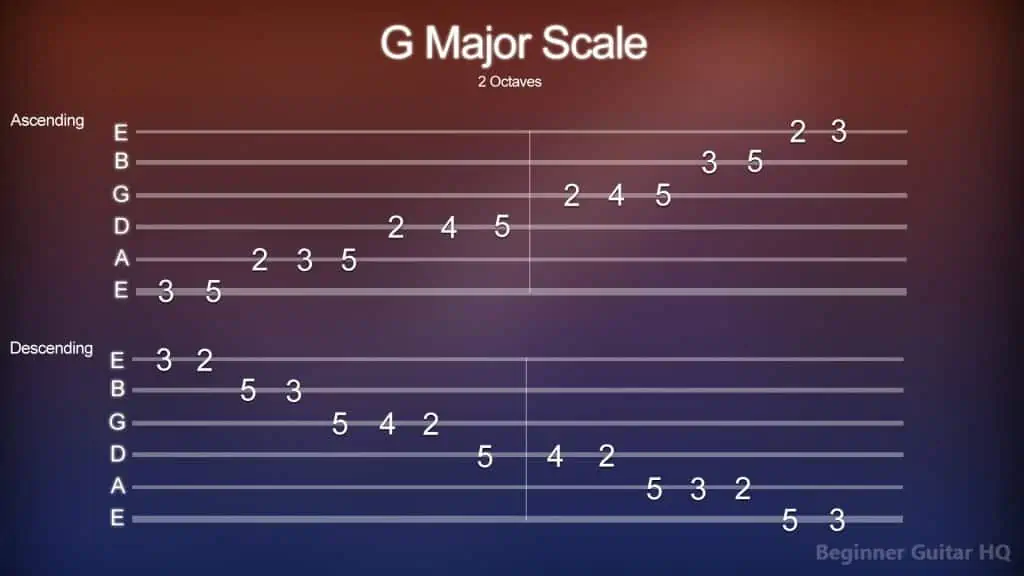

The key of G is relatively simple to play in. In fact, playing scales can be an excellent way of improving your finger strength, dexterity, and fretboard knowledge. Here is the G major scale written in tablature (tab), ascending and descending:

The G major scale is displayed in tab form, starting from the third fret.

Reading Tablature

Tablature, or tab for short, is an alternative to reading sheet music for the guitar. As you can see, from the bottom line to the top line, you have your low E string, followed by A, D, G, B, and your high E string. Each of the numbers on each string represents a note to be fretted on the corresponding string. For instance, you have your low E string with the numbers “3” and “5”. This indicates that you are to play the third fret of the low E string, followed by the fifth fret on the same string. This continues to escalate up the scale before coming back down.

Different from chord charts, tablature won’t display the correct fingering for each fret. A good rule of thumb to follow when playing scales is to make sure it all fits within your hand by looking at the lowest fretted note. As you see within this scale, you might look and think, “it must be 3! So I’ll put my index finger there, since that’s where the scale begins!”, but it might make more sense to instead put your middle finger there as the following string has a note on the 2nd fret.

Looking at what notes you have to play before attempting to play them is an excellent practice to get into. It will help you exercise proper finger placement so that you don’t develop any bad habits!

The Gmaj Chord

The G major chord is identified by the triad of notes: G, B, and D. A triad is a type of chord defined as a grouping of three notes played simultaneously. The characteristics of a major triad involve these specific intervals:

- Major 3rd (from the tonic to the mediant)

- Minor 3rd (from the mediant to the dominant)

- Perfect 5th (from the tonic to the dominant)

This gives the chord an overall happy or uplifting sound. If we would like to further understand our G major triad, we should go over its key signature and the resulting scale.

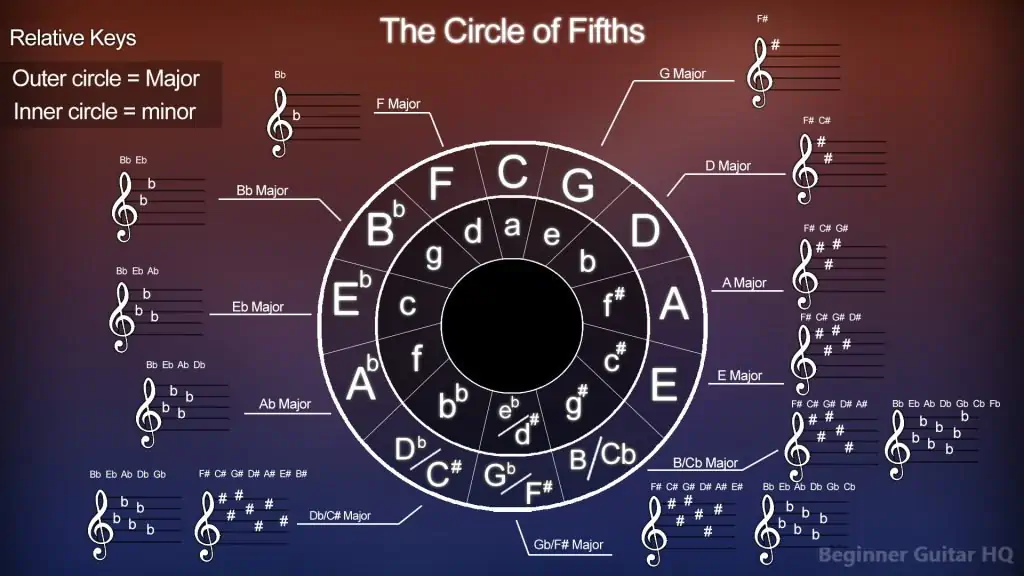

To find our key signature of G major, we should consult the circle of fifths. The circle of fifths can be described as “a wheel-shaped diagram depicting all of the most commonly used key signatures in major and minor”. As you can see, the wheel contains two rings: the outer ring is for every major key/key signature, while the inner ring is for its relative minor; a key with the same key signature, but a different tonic.

A diagram of the circle of fifths, showing the most commonly used key signatures.

Starting from C Major/A minor, as you go clockwise around the ring the keys will gradually gain more and more sharps (a note to be raised by a semitone). This happens until you hit C# major/A# minor on the wheel, containing 7 sharps. Going counterclockwise starting from the same point, the keys will gradually gain more and more flats until you hit Cb major/Ab minor, containing 7 flats.

However, this is not to say that you can’t go beyond that. That is where you start getting into some weird territory of key signatures containing double sharps and double flats. For simplicity’s sake, we won’t go into that.

Our key of G major contains but one sharp, F#. How is this determined though?

You simply need to remember the acronym: FCGDAEB. Which stands for:

“Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle”

The first letter of each word depicts a note that is to be sharp. As you go clockwise around the wheel, more of these letters are added:

C = No sharps or flats.

G = F

D = F, C

A = F, C, G

E = F, C, G, D

B = F, C, G, D, A

F# = F, C, G, D, A, E

C# = F, C, G, D, A, E, B

Likewise, if you wanted to find your flat keys, you would have to reverse the acronym, making it: BEADGCF. This stands for:

“Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’, Father”

As you go counterclockwise, each key would gain an additional flat in its key signature:

C = No sharps or flats.

F = B

Bb = B, E

Eb = B, E, A

Ab = B, E, A, D

Db = B, E, A, D, G

Gb = B, E, A, D, G, C

Cb = B, E, A, D, G, C, F

The idea behind it is that you only really need to remember how many sharps or flats each note has and use this acronym to figure out which notes these are. For instance, the key of E contains 4 sharps. Using our fingers, we would count to four, saying: “Father, Charles, Goes, Down.” right there, we’d know that the notes F, C, G, and D are our sharps in the key of E major.

It’s recommended that you start with one half of the wheel, like the sharps, and try memorizing how many each key has. Once you’ve gotten this down, you may use this knowledge to figure out the other half of the wheel! The only thing you need to know is the number 7. Going back to our earlier example, the key of E major has 4 sharps, F, C, G, and D. If we wanted to know how many flats Eb major has, we would subtract 4 from 7, giving us 3. Therefore, the key of Eb major contains three flats, B, E, and A. It’s as easy as that!

Identifying a key signature is important because this defines the notes played for your scales and chords in correspondence to the key you’re in. Let’s take our G major scale. We know that the key of G major has only one sharp, F#. Therefore, when we look at our scale, it would look something like this:

G > A > B > C > D > E > F# > G

Major scales have a cookie-cutter pattern that they must always follow made up of 5 tones (T) and 2 semitones (S). Which looks like this:

T > T > S > T > T > T > S

As you can see above, the G major scale is no different than any other major scale, in that it follows this pattern as well. B and C are a semitone apart, and F# to G are a semitone apart as well. The rest of the notes are tones.

Now, every note within our diatonic scale (scales with 5 tones and 2 semitones) contain a special name corresponding to what degree it has within our scale. Within the key of G major, they are:

G = Tonic (1st Degree)

A = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

B = Mediant (3rd Degree)

C = Subdominant (4th Degree)

D = Dominant (5th Degree)

E = Submediant (6th Degree)

F# = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

G = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

The triad of G major relies on the 1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees of the scale (Tonic, Mediant, and Dominant). This gives us the notes G, B, and D used for our G major chord.

Making the G7 Chord

By now, you know how to play your G7 chord on guitar, but how does it work? It involves us taking our existing G major triad, and throwing the 7th degree (leading tone) of our scale on top. This gives us the notes, G, B, D, and F# to complete our G7 chord. This formula of taking our major triad and throwing a leading tone on top can be done to make other major 7th chords: A7, B7, C7, D7, E7, and F7.

G7 into Gm7

In the case where we wanted to make ourselves a Gm7 chord (G minor 7th), we would need to first understand the key signature of G minor. G minor shares a key signature with its relative major Bb major, giving it two flats, B, and E. Knowing this, we can form our scale:

G > A > Bb > C > D > Eb > F > G

Like major scales, minor scales follow their own set of tones (T) and semitones (S). The pattern goes by:

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

Every note within our minor scale falls into the corresponding degree:

G = Tonic (1st Degree)

A = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

Bb = Mediant (3rd Degree)

C = Subdominant (4th Degree)

D = Dominant (5th Degree)

Eb = Submediant (6th Degree)

F = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

G = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

To form our minor triad, we would take our 1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees (tonic, mediant, and dominant) like we have done with our major triad counterpart. This gives us the notes: G, Bb, and D. A minor triad’s intervals are essentially a reverse of a major triad in which:

- Minor 3rd (from the tonic to the mediant)

- Major 3rd (from the mediant to the dominant)

- Perfect 5th (from the tonic to the dominant)

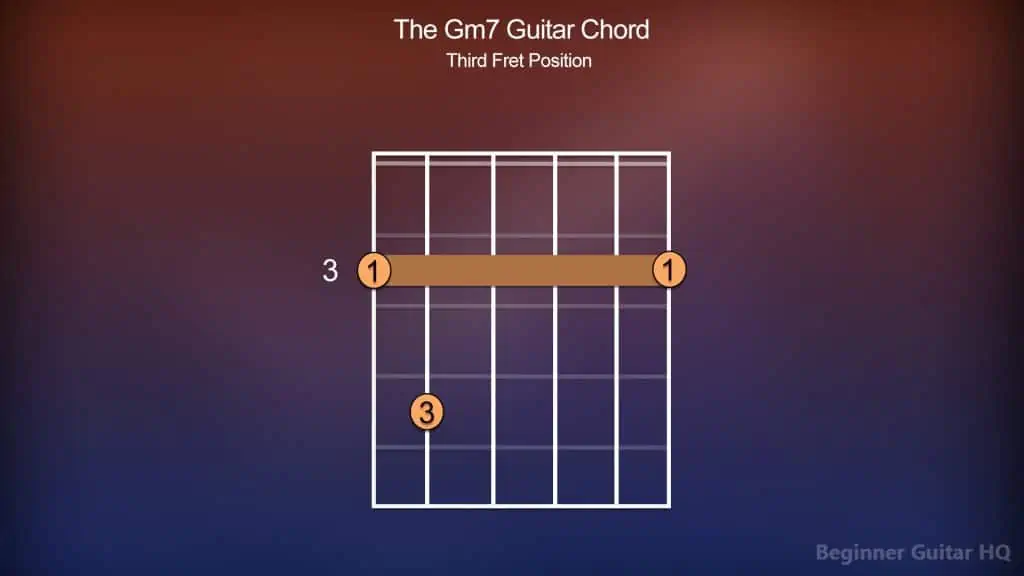

To complete our Gm7 chord, we need to add our 7th degree (leading tone) to our triad, making the notes of the chord: G, Bb, D, and F. We now have our Gm7 chord.

The Gm7 guitar chord chart played from the third fret.

Chords that go well with G7

Have you ever struggled with making a nice chord progression? Don’t worry, we’ve all been there. Thankfully, there is a tried and true method of making this task much easier! It’s all based around building triads along every note within the key of G to form compatible chords for your chord progression. The following are the triads of G major, with their seventh note in brackets:

- G Major = G, B, D, (F#)

- A minor = A, C, E, (G)

- B minor = B, D, F#, (A)

- C Major = C, E, G, (B)

- D Major = D, F#, A, (C)

- E minor = E, G, B, (D)

- F# diminished = F#, A, C, (E)

Here are some common chord progressions in the key of G:

- ii > V > I = (Amin7 > Dmaj7 > Gmaj7)

- I > IV > V = (Gmaj > Cmaj > Dmaj)

- I > vi > IV > V = (Gmaj > Emin > Cmaj > Dmaj)

The first chord progression listed here is otherwise known as the “two-five-one turnaround”, a common chord progression widely used across various genres, but is the most common in jazz music. As the name implies, you have it start on the 2nd degree, the supertonic, a pre-dominant chord. The supertonic can act as a worthy substitute for the 4th degree, the subdominant chord as they share many of the same notes. To increase the tension from the 2nd degree, we will move to the 5th degree, the dominant. The tension is at its peak, it will now beg for resolve, thus it will move to the 1st degree, the tonic, and end there.

The second chord progression listed doesn’t use seventh chords, but it still falls within the key of G. Now, you’ll start on the tonic, the root note, and transition to the fourth degree, the subdominant. This degree of the scale will create some tension and build upon that when it transitions again to the dominant. Finally, it will want to resolve and return back to the tonic.

For the third and final chord progression listed here, you will once again start on the tonic. It will now transition to the sixth degree, the submediant, which acts as a “predominant” chord, sharing two notes within the tonic chord, and two within the subdominant. Transitioning from the submediant, we will move to the subdominant, which builds more tension. Finally, we move to the dominant, at the peak of our tension, and resolve back on the tonic.

Inversions

Did you know that there are multiple ways to play a chord? This can be achieved by changing the intervals within the chord without changing the note, but rather, changing the octave. We may call these “inversions”. Since we are working with seventh chords we have three inversions. Here are the inversions for our G7 chord:

- Root Position: G > B > D > F#

- 1st Inversion: B > D > F# > G

- 2nd Inversion: D > F# > G >B

- 3rd Inversion: F# > G > B > D

Normally, if we were working with chords consisting of a simple triad like C major, Eb major, or F major, then we would only have two inversions. However, this changes as more notes are added to a chord. For example, when you have a ninth chord that contains four inversions, an eleventh chord, containing five inversions, or a thirteenth note containing six inversions.

Playing piano, inversions can be fairly straightforward as you are playing in a linear space, moving from left to right across the keys. However, for guitar, this might seem a little trickier as you can move left to right up the neck, but also vertically across six strings. A simple way to tackle inversions on the guitar is to think of your notes moving linearly. For instance, you can use four strings for your seventh chords, such as your low E, A, D, and G strings, and focus on moving up the neck with inversions using the same strings. This helps keep things relatively simple and familiarizes yourself with different notes on the fretboard the more you do it.

Practicing with a metronome can be an excellent means to improve your timing on the guitar. There are several different exercises you may choose, such as the aforementioned inversions, chord progressions, scales, spider exercises, and more! It’s important to change up your practice routine every now and again to keep things fresh, interesting, and fun!

Conclusion

Now you have all of the tools at your disposal to get started with the G7 chord and learn other seventh chords. They are a great resource for adding some character to your music and keeping your chord progressions from sounding stale.

It’s always important to find new ways of challenging yourself on the guitar to keep yourself interested in playing, but also to keep growing as a musician! Beyond seventh chords, will you go as far as to learn ninth, eleventh, or thirteenth chords? Perhaps you’ll mix things up and try learning some augmented and diminished chords? Wherever your practice takes you, enjoy the ride and keep on rockin’.