Seventh chords have such an interesting sound and can really add some color and character to a chord progression. The A7 chord is no exception and is very easy to learn, and add to your musical repertoire! Let’s go over it in further detail, and learn how you can start using the A7 chord today!

Contents

About Seventh Chords

There are many famous songs that utilize seventh chords in their chord progressions. Songs like, “Hallelujah by Jeff Buckley”, “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction by Rolling Stones”, or even “Nothing Else Matters by Metallica”. However, where seventh chords are most commonly used lies in the world of Jazz and Blues music. Of course, however, seventh chords may be used in other modern genres of music like hip-hop, neo-soul, and deep house.

So, why use seventh chords?

Seventh chords can be an excellent addition to a chord progression, adding more character, and color. A seventh chord may be used to bring additional tension to a progression as you approach the tonic, where things tend to resolve. Seventh chords are formed from the base triad of notes within the chord and adding the 7th interval from the tonic on top. The seventh degree, the leading tone, is what comes right before hitting the tonic, the root note, so there’s already a lot of tension there as you hear it. Naturally, your ears will want it to resolve on the note after. This is a fairly simple reason why it works so well as a “tension builder”.

As a musician, naturally, adding more chords to your musical repertoire can only add greater benefit to your knowledge and skills. Starting out, however, on the guitar you’ll find that the open position seventh chords are fairly easy, if not easier than the standard major/minor chords. Which, as a beginner, is all the more reason to learn them! As a more experienced guitarist, you are welcome to learn them in other positions up the neck, as this will provide you with a greater challenge, and more musical variation.

Playing the A7 Guitar Chord

The A7 guitar chord is extremely simple to play. In fact, if you already know how to play your A major chord, then this gets even easier! Let’s take a look:

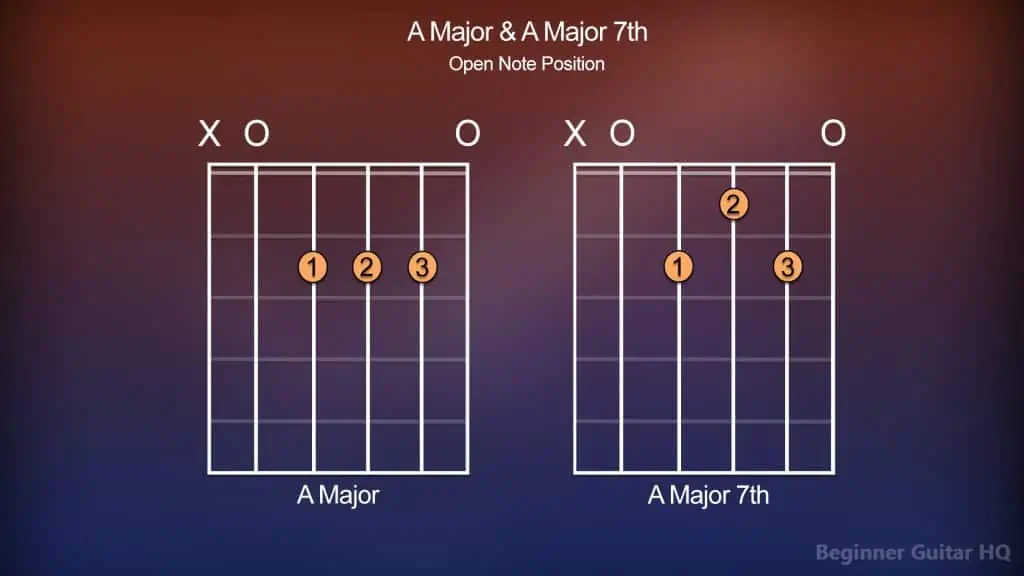

A couple of chord charts of the A major chord, and A major seventh chord from open note position.

As you can see, the shapes of the two chords are very similar! In the A major chord shape, you have your index, middle, and ring finger sitting on the 2nd fret of the D, G, and B strings. The only difference the A major 7th chord has is that the note on the G string gets shifted to the 1st fret, while the other fingers stay in the same place. Give it a good strum from the A string all the way to the high E string. There you have your A major 7th chord. It’s as easy as that!

Trouble With Chord Charts?

As a beginner, looking at one of these for the first time was extremely confusing! However, it’s not as hard as it looks! The big rectangle with the lines is meant to represent the fretboard. Each vertical line is meant to represent a different string. From left to right, you have the low E string, followed by the A, D, G, B, and lastly, the high E string. The horizontal lines, however, are what separate one fret from the next.

You’ll notice how there are tiny circles with numbers 1 – 4 labeled in them. These are meant to represent which fingers you are supposed to use to complete the chord. The number 1 is for your index finger. The number 2 is for your middle finger. The number 3 is for your ring finger. Finally, the number 4 is for your pinky finger.

On some chords, you maybe also see an “O” or an “X” above the fretboard. The O is what represents an open note (a string to be played but not fretted). The X represents a string that is not to be played to complete the chord. Lastly, you may have a number to the left of a fret on the fretboard, which is to indicate the starting fret for the chord. Not all chords will have this indicator as when playing in the open-note position just implied you are playing from the first fret.

The Key of A Major

To truly understand how our A major chord works, it can be helpful to understand the key of A major first! The three components that form the basis of the A major chord involve the key signature, scale, and triad.

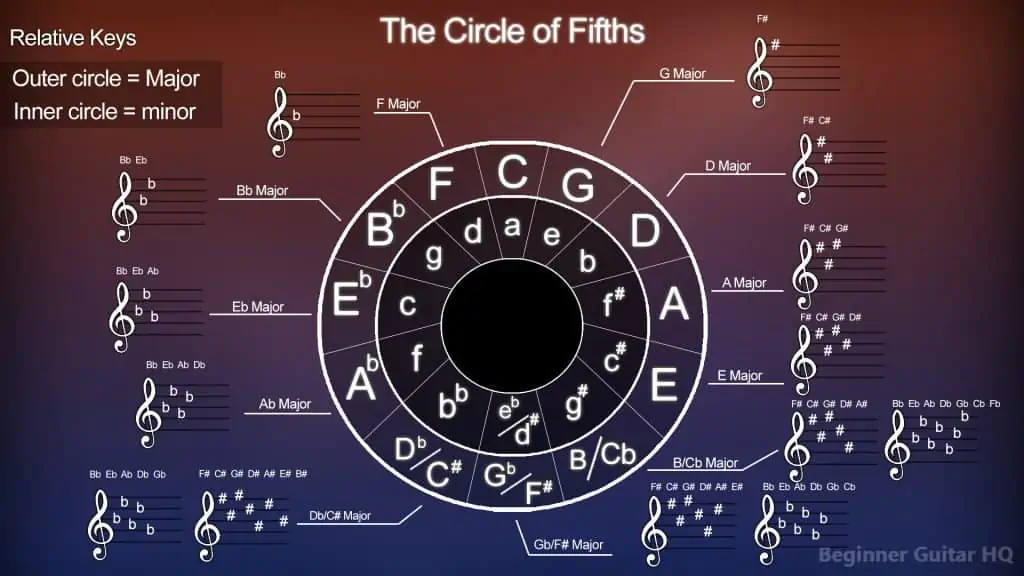

We’ll begin by going over the key signature first. To find a key signature of any specific key, it can help by consulting the circle of fifths. The circle of fifths is a wheel-shaped diagram showing the most commonly used keys and their corresponding key signature.

The Circle of Fifths diagram displaying the most commonly used key signatures.

The outer wheel of our diagram displays our major keys, the inner wheel displays our relative minor keys (keys that share the same key signature as our major keys). As you go clockwise around the wheel, you will notice that each key gains an additional sharp note in its key signature. From the key of C, containing no sharps or flats, all the way to C# containing all 7 sharps. You might ask, how do we know which notes are sharp in the key? The answer lies in a helpful acronym: FCGDAEB, which stands for:

“Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle”

Each word in this saying is to represent a different note that is to be sharp, following this sequence. Here is how it looks in action:

C = No sharps or flats.

G = F

D = F, C

A = F, C, G

E = F, C, G, D

B = F, C, G, D, A

F# = F, C, G, D, A, E

C# = F, C, G, D, A, E, B

The idea is that we remember how many sharps are in each key. So for instance, if we knew that B major has five sharps in its key signature, then using the acronym, and possibly our fingers too, we would say “Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And”. Therefore, our sharps within the key of B major would be F, C, G, D, and A.

One misconception about the circle of fifths is that it ends at C#/Cb as it contains all seven notes as sharps or flats within the key signature. However, it can actually go beyond that. This is when you start entering the realm of whacky key signatures containing double sharps, and double flats on certain notes. For simplicities sake, we will focus on everything up until our C#/Cb.

Now, on the otherhand if you wanted to find the key signature of a flat key like Ab major, then you simply need to reverse our acronym from before, making it: BEADGCF. This would stand for:

“Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’, Father”

This gives you the following flats in sequence as you go counterclockwise down the circle of fifths:

C = No sharps or flats.

F = B

Bb = B, E

Eb = B, E, A

Ab = B, E, A, D

Db = B, E, A, D, G

Gb = B, E, A, D, G, C

Cb = B, E, A, D, G, C, F

However, since you would already know the right half of the circle of fifths, all you need to do from there is to keep the number 7 in mind. To find the key of Ab major, lets look at our key of A major, containing 3 flats. Subtracting 3 from the number 7, we get the number 4. The key of Ab major contains 4 flats; B, E, A, and D.

You can use this method to find out the key signatures on the other half of the circle of fifths, its as easy as that!

On the topic of A major, our key signature only contains three sharps in its key signature. Using our same method, we can figure out that the key of A major has the sharps F, C, and G in its key signature.

Now, we’ll move onto our A major scale. We know already that our A major scale contains the sharps, F, C and G. Here’s how they fit into our scale:

A > B > C# > D > E > F# > G# > A

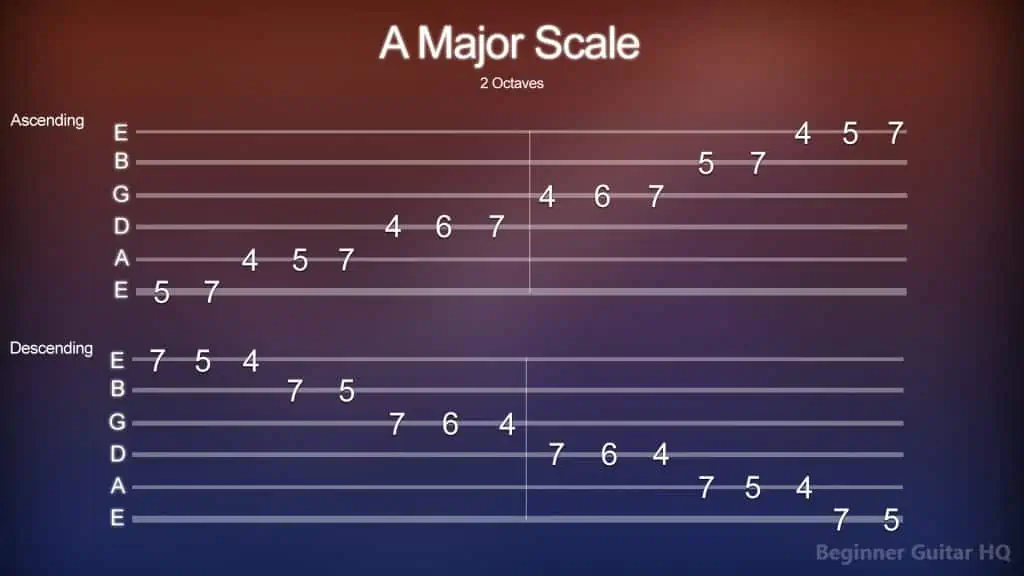

Here is how we play it in tablature form:

The A Major Scale ascending in descending in tab form.

Reading Tablature

Tablature, or tab for short, is an alternate way of reading sheet music, in a more dumbed-down way. As you can see, there are six horizontal lines, each with a corresponding string note. From the bottom to the top we have the low E string, followed by the A, D, G, B, and high E string. The number on each line represents the fret you need to play.

The proper finger position isn’t implied in tablature as chord charts do, so looking ahead to what you need to play is important. The best way to go about this is to look at what would fit best in your hand. You may see that the lowest fret on the scale is the 4th fret, and the highest is the 7th. Therefore, it might be best to start your scale on the middle finger, play the 7th fret with your pinky, and use your index on the 4th fret. Finger positioning is important. This is why planning ahead on what you’re going to play, and how you’ll play it is detrimental to maintaining good habits.

More on A Major

Within a major scale, we have a pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) which goes as follows:

T > T > S > T > T > T > S

As you will notice within our A major scale, it follows this pattern to a tee. C# and D become a semitone apart, as do G# and A. However, B and C# become a tone apart, as do F# and G#. Moving forward, the notes in our scale all have their own identifiers based on what degree in the scale they are. In our A major scale, these go as follows:

A = Tonic (1st Degree)

B = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

C# = Mediant (3rd Degree)

D = Subdominant (4th Degree)

E = Dominant (5th Degree)

F# = Submediant (6th Degree)

G# = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

A = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

These degrees each have an important role to play, as in major triads, they are formed on the first degree, the tonic. The third degree, the mediant. Finally, the fifth degree, the dominant. Triads are a type of chord formed by playing three notes in unison. Major triads all share a similar characteristic within the intervals of their notes. The intervals are:

- Major 3rd (From the tonic to the mediant)

- Minor 3rd (From the mediant to the dominant)

- Perfect 5th (From the tonic to the dominant)

In your typical triad, you can form what is known as inversions. An inversion is an “inverted chord”, which can be achieved by shifting the note placement elsewhere by an octave. Within a major triad, you can form two types of inversions; a first inversion, and a second inversion. Here is how they look within our A major triad:

- Root Position: A, C#, E

- 1st Inversion: C#, E, A

- 2nd Inversion: E, A, C#

When we make our A major seventh chord, we now get three inversions which change things like so:

- Root Position: A, C#, E, G#

- 1st Inversion: C#, E, G#, A

- 2nd Inversion: E, G#, A, C#

- 3rd Inversion: G#, A, C#, E

As we mentioned earlier, a triad is a type of chord. There are several different types of chords you can make, like a ninth chord, containing four inversions. An eleventh chord, containing five inversions. Even a thirteenth chord, which contains six inversions.

Inversions can give you some very creative new ways to play a chord. It’s highly recommended to look into the CAGED system for more insight into playing chords from different positions.

Chords In the Key of A

Chord progressions can be fairly easy to make, however, finding one that sounds nice and fits within your key can be a challenge to some. Thankfully, there is a very simple solution, and it’s all centered around triads. Since now you know how triads work, what we are going to do is form a triad on each individual degree of the A major scale. Here’s how it looks:

A Major: A, C#, E (G#)

B minor: B, D, F# (A)

C# minor: C#, E, G# (B)

D minor: D, F#, A (C#)

E Major: E, G#, B (D)

F# Major: F#, A, C# (E)

G# Diminished: G#, B, D (F#)

As a note, the letter within the brackets is our note we need to turn our triads into seventh chords. Using these chords, we have the tools needed to form our own chord progressions.

There are many ways you can go about forming your chord progressions, but oftentimes using the tried and true method is a great place to start. Using your scale degrees is a great tool for finding the impact a chord will have within your key. Here are a few chord progressions you might choose to follow:

- (I – IV – V): A > D > E

- (I – vi – IV – V): A > F#m > D > E

- (ii – V- I): Bm7 > E7 > A7

For our first progression, we start on the first degree of our scale, the tonic. Following the tonic, we transition to our fourth degree, the subdominant. The subdominant is typically a degree that adds some light tension, and a good bridging chord to the fifth degree, dominant that follows. The dominant creates the most tension and begs for resolve, which then makes the logical transition back home to the tonic.

Our second progression is otherwise known as the 50s progression. This starts on the tonic, and from there we’ll be moving to the sixth degree, the submediant. The submediant is great for expanding on our tonic, as it shares two notes with the tonic and can work as a “predominant chord”. From there we’ll be moving from the submediant to the subdominant, adding a little more tension to the progression. From there, we have the natural movement from the subdominant to the dominant, at the peak of our tension. Naturally afterwards, the dominant will resolve back on the tonic.

For our third progression, also known as the two-five-one turnaround, a common progression used in the world of Jazz music, untilizing seventh chords. We start on our second degree, the supertonic this time, a “predominant” degree. This degree in particular works as an excellent substitute for our fourth degree, as they share many of the same notes. The supertonic, already carrying some tension, will now transition the a degree with even more tension, our fifth degree, the dominant. Finally the dominant will want to resolve, so it will transition back down to our tonic.

Parallel Minor to A Major

We’ve briefly touched on relative minors when discussing the circle of fifths, in that they share the same key signature. However, what exactly is a parallel minor, or a parallel key in general?

To sum this up: a parallel key is a key that shares the same tonic, but carries a different key signature.

Within the key of A major, we have three sharps F, C, and G sharp. However, in the key of A minor, we actually have no sharps and no flats. In fact, A minor is the relative minor of C major. The scale of A minor looks like this:

A > B > C > D > E > F > G > A

Now, the key of A minor is pretty good for seeing how the pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) differs in a minor scale compared to a major scale:

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

As you can see, the A minor scale has a semitone of B to C, and E to F, while the rest are tones. None of the notes have been altered with sharps or flats.

Our minor triads follow a similar pattern to our major triads, however, their intervals are different:

- Minor 3rd (From our tonic to our mediant)

- Major 3rd (From our mediant to our dominant)

- Perfect 5th (From our tonic to our dominant)

As you can see, the same scale degrees are used, but due to the shift in pattern between tones and semitones used in a minor scale, this changes our triad. This makes our A minor triad the notes: A, C, and E.

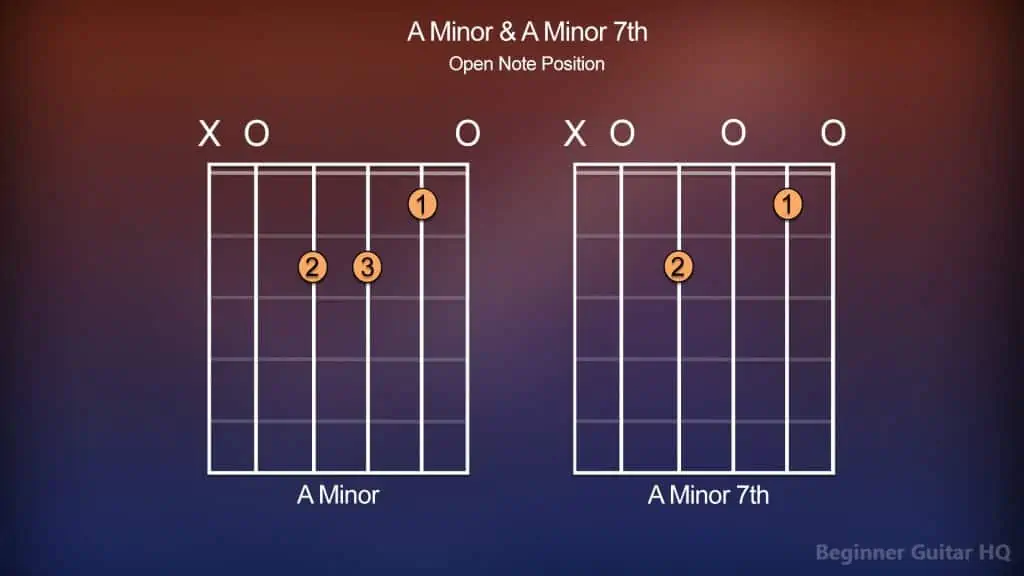

When we make an A minor 7th chord (Am7), we add G on top of our E, making the chord: A, C, G, and E. Here is our we play our A minor and A minor 7th chords:

The A minor chord and A minor 7th chord displayed on chord charts.

Conclusion

Now you have everything you need to get started with your A major 7th chord! Seventh chords have a really nice and colorful sound, as they can really breathe life into an otherwise dull chord progression. They are excellent for adding as well as relieving tension depending on how they are used.

The important thing with chords, especially as a beginner, is to take things slow and not to get discouraged if they don’t sound great. This could be anywhere from buzzing strings, muted notes, or even wrongly played notes. You will increase your finger strength and muscle memory over time, and this will get easier. You just need to persevere and more importantly, have fun practicing.

How will you implement seventh chords into your practice routine? What will you do to implement the information attained here to your songwriting? Wherever your pracitce takes you, keep on rockin’.