Learning chords can be incredibly beneficial to musicians alike, whether you’re learning theory, building finger strength and dexterity, or just looking for more colors to add to your musical palette. The Bb chord is no exception and may help you achieve any one of these goals. Intrigued? Well, let’s dive in!

Contents

Why Learn Different Guitar Chords

It doesn’t hurt to further your understanding of the “why” before learning “how”. In fact, understanding why you should know the Bb guitar chord, or any chord in particular may spur you on to take things further. Here are a few reasons why you should learn guitar chords:

They’re fun! I feel that this point is important in mentioning first because it’s important that you have fun playing the guitar and not feel like it’s a chore. Chords are the foundation of most campfire songs and are great for jam sessions. Furthermore, they can lead to other methods of practice, for instance, looking at the CAGED system, scales, or arpeggios, to name a few.

It can improve your finger strength. Finger strength can go a long way. When you’re starting out on the guitar, your dominant fingers may be your index and your middle finger, while the ring and pinky fingers may feel a little awkward. The more you play chords, especially barre chords, the more often you will be using all four of these fingers.

However, it’s worth noting that in an open-string position, that’s not always the case and if you’re a beginner that’s likely where you will begin learning chords. As you move up the neck, that is where the use of all four fingers becomes more common.

It can improve your finger dexterity. Improving dexterity is an ambition of most guitarists, and many spend hours upon hours perfecting different scales, patterns, and riffs. When it comes to chords, practicing different chord progressions may help you improve the muscle memory in your fretting hand by getting used to different chord shapes. You may even choose to practice arpeggios, as they are a great way to improve dexterity in your picking hand, by means of down-up picking.

Chords may also act as a gateway to improving your dexterity from other methods. If we take the Bb Major chord, we can also find that it has its respective scale, the Bb Major scale. Performing exercises on these related scales is a fairly common way to improve finger dexterity.

It may strengthen your ear. An ear for music is something that is developed over time. The more that you hear and get familiar with these different chords, the more natural it will become to identify them. Another great means of improving your ear is through interval training, which will come as an asset when learning more about the music theory of guitar chords.

It can help you improve your guitar theory. There are many amazing and successful musicians out there who didn’t know a lick of music theory. Although could you imagine if they did? Music theory is not a must, however, it is an asset. Understanding music theory can play a part in how you write music, and how you improvise and make use of dynamics and tempo. Music theory has a hand in everything you do on your instrument because it helps you understand the method behind the madness of music in general.

It can add more color and variation to your music. This ties into the former point of guitar theory, in terms of writing, and composing music. It’s helpful to know what chords can set the mood you’re looking for, build tension, and resolve. Sometimes you’ll find certain chords that sound very nice together, and some that don’t. A helpful way to analyze this is to look at the most common chord progressions used in pop today, you’ll be amazed!

It can build up your confidence in your playing technique. When you see a musician on stage having a great time and making wondrous sounds with their instrument, it comes from a place of confidence. The more you learn about the guitar and practice what you learn, the more confidence you will amass. Chords are but one layer in the greater whole of improving yourself as a guitarist.

How to Play the Bb Guitar Chord

As a beginner, you may find that learning to play barre chords can be challenging, however, if you keep at it, it only gets easier. In fact, learning to play barre chords can help you play chords in other positions up and down the neck, as done in the CAGED system.

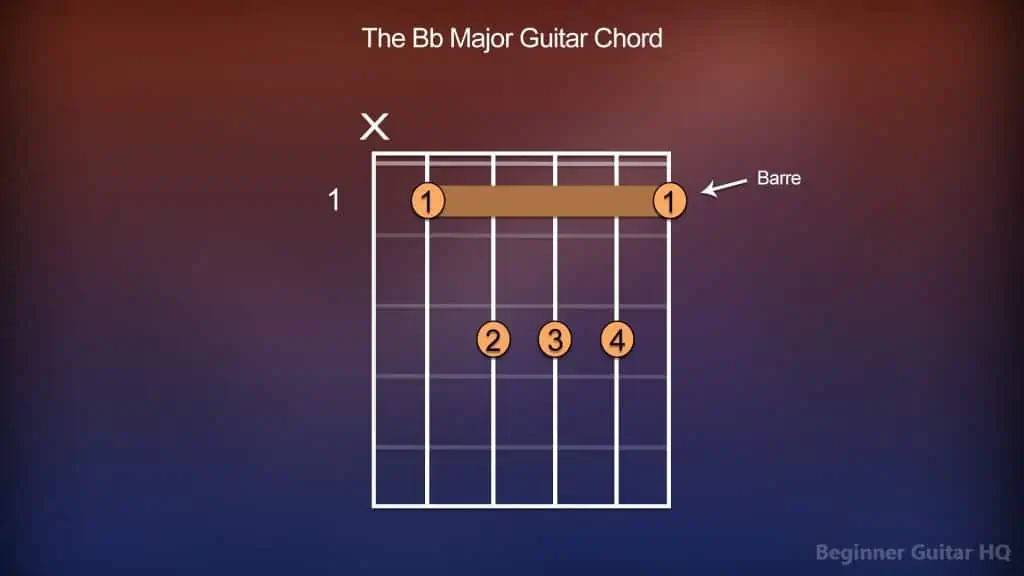

As you’ll see in the diagram below, the long stretch of notes over a single fret is what we refer to as a “barre”, and this is what makes the Bb Major chord, a barre chord. To play this barre chord, you will need to lay your index finger vertically across the strings over a single fret.

As mentioned before, this will be slightly uncomfortable.

You want to apply pressure on each string you’re covering with that finger, and do your best to not receive buzzing or muted notes when strummed.

A chord chart showing how to play Bb Major on Guitar.

New to Chord Charts?

The rectangle you see before you represents a fraction of the fretboard. You may sometimes see a number off to the left indicating what fret you are on, however, when you don’t see a number that means you’re in an open chord position (where some of the notes of a chord may include an open string).

Each number on the vertical strings represents what finger is meant for that string. The index finger is (1), the middle finger is (2), the ring finger is (3), and the pinky finger is (4). For the barre chord, you will see a line with the number (1) on both ends. That is where the start and end points are for our barre.

The X you see above the fretboard diagram is to display that this string is not to be played. However, if you see an O, then that indicates that this is an open note, part of the chord.

What Makes the Bb Major Chord?

The Bb Major Chord is built on the triad of notes, Bb, D, and F. To understand why these notes are what make the Bb Major Chord what it is, we need to understand two things: the key signature, and the scale.

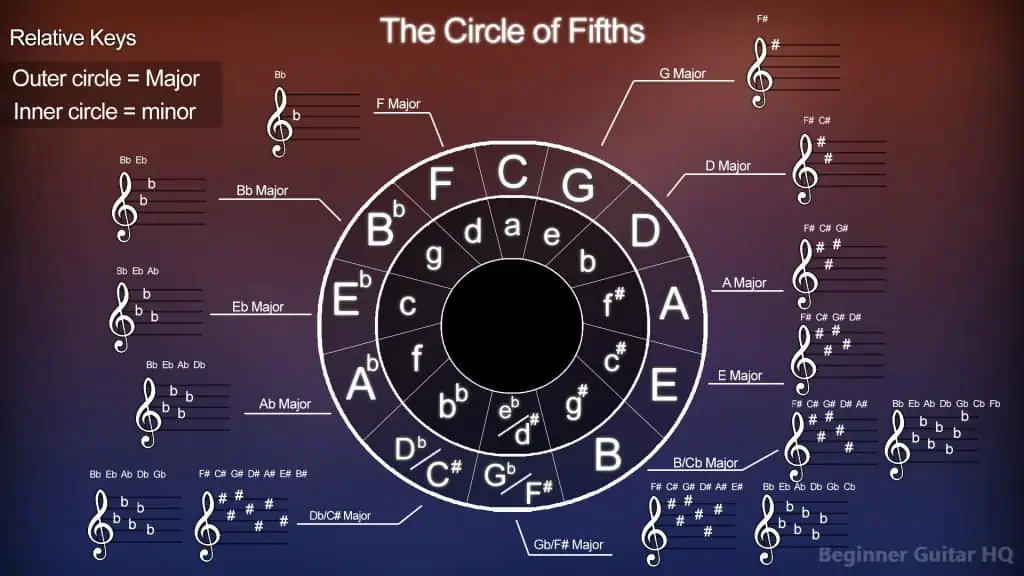

A diagram showing every Major and minor key signature contained within the circle of fifths.

The key signature can be found using what’s known as the circle of fifths. If we look at the diagram we can see that Bb Major contains two flats. How we can identify which notes are flat in this key is by using the acronym: BEADGCF, also known as Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles’ Father. If we were dealing with a key containing sharps, like B Major, this would be reversed: FCGDAEB, also known as Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle.

However, since we’re learning about Bb Major, we’ll stick to using the flats.

The sharps and flats of the key are indicated in the order of the letters listed in the acronym:

1 flat: B

2 flats: B, E

3 flats: B, E, A

4 flats: B, E, A, D

5 flats: B, E, A, D, G

6 flats: B, E, A, D, G, C

7 flats: B, E, A, D, G, C, F

This is how we know that Bb Major contains two flats, which are the B and E notes. When a note is flat, that means that the note is to be lowered a semi-tone, or half step. Contrary to a note that is sharp, being raised a semitone. With this information, we can now move on to the Bb Major scale.

In western music, we traditionally use diatonic scales, which consist of five tones and two semitones. Since we are in a Major key, the pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) would appear as, T – T – S – T – T – T – S. To follow this pattern correctly, we need to introduce our key signature to make these tones and semitones are accurate. Therefore, the scale would look like this:

Bb > C > D > Eb > F > G > A > Bb

First, let’s note that we have our two flats in the key of Bb Major, the B, and E. The Bb to the C allows room for a tone, as B and C are naturally a semitone apart. The same goes for Eb and F. When we go from D to Eb, we have a semitone now, and the same goes for A to Bb. This is the makeup of the Bb Major scale.

So how does the Bb Major scale tie into the Bb Major chord?

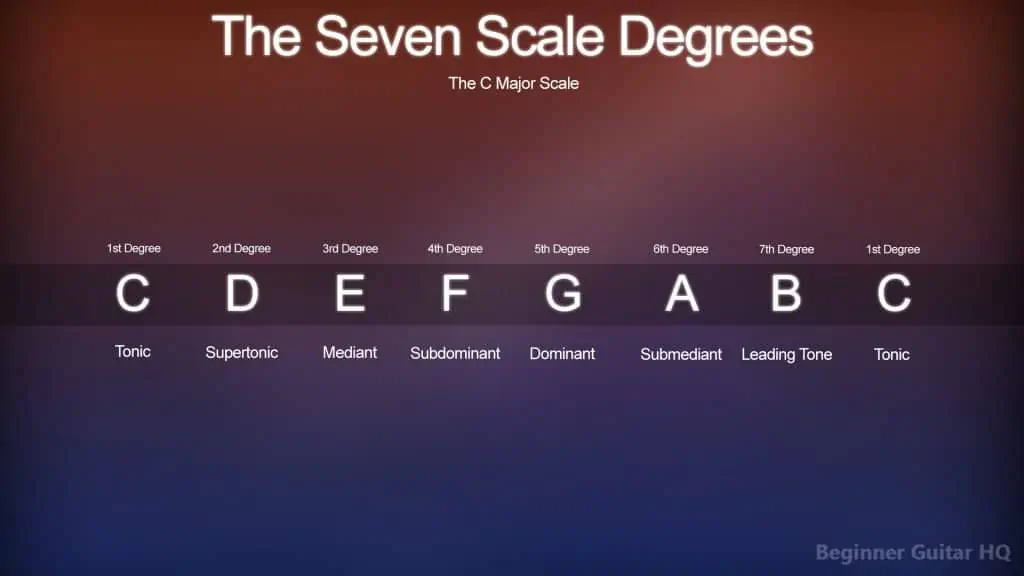

In a nutshell, we’d use the first, third, and fifth degrees of the scale to make our Bb Major chord. These degrees of the scale might otherwise be known as the tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees of the scale. So if we take a look at our scale, the first, third, and fifth degrees would be Bb, D, and F to build our Bb Major chord. Pretty simple!

Triads provide the foundation for building an assortment of different major, minor, augmented, and diminished chords. An important distinction, however, is that all triads are chords, but not all chords are in fact triads. This is where the 4th, 7th, 9th, and 13th chords come into play, creating very unique colors.

Variations of the Bb Guitar Chord

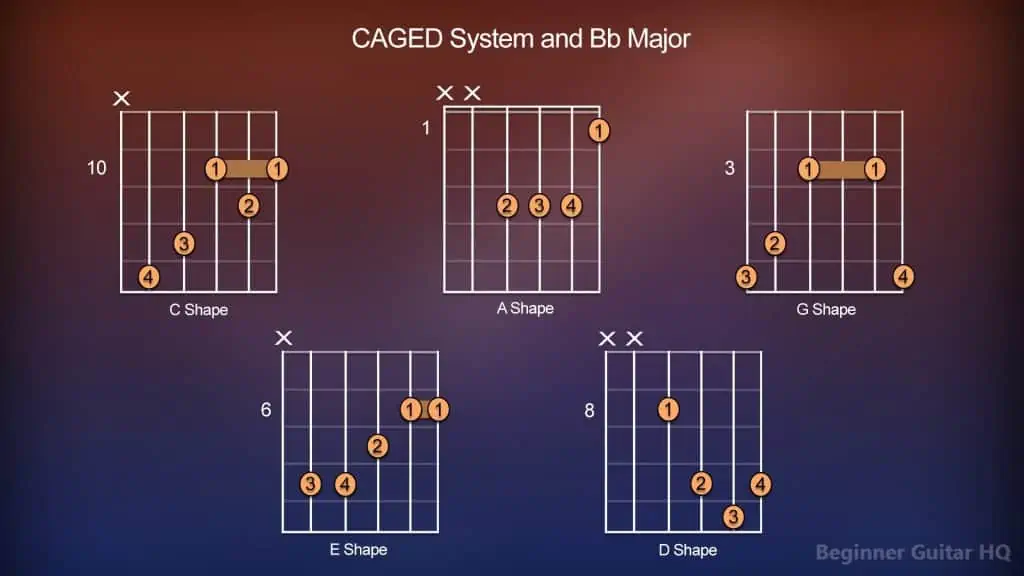

The guitar is a slightly different beast than the piano, and this fact alone may confuse a lot of people when it comes to the fretboard. When you play the piano, it’s fairly simple to transpose chords up and down to different pitches and octaves. The guitar, however, because of its natural tuning and layout (EADGBE), doesn’t make things so straightforward. This is where things like the CAGED system can help beginners understand and visualize the fretboard in an easier way.

The CAGED system is an acronym for five different chord shapes: C, A, G, D, and E Major. These chord shapes all relate to the next and continuously flow, helping you build and transpose the next chord up, or down the neck of the guitar. The C shape will lead to the A shape, the A shape will lead to the G shape, and so on. When you make it to the E chord shape, it will flow back to C making it an octave higher from where you began. Here is a diagram of the CAGED system chords for Bb Major:

CAGED system chord charts for the Bb Major chord.

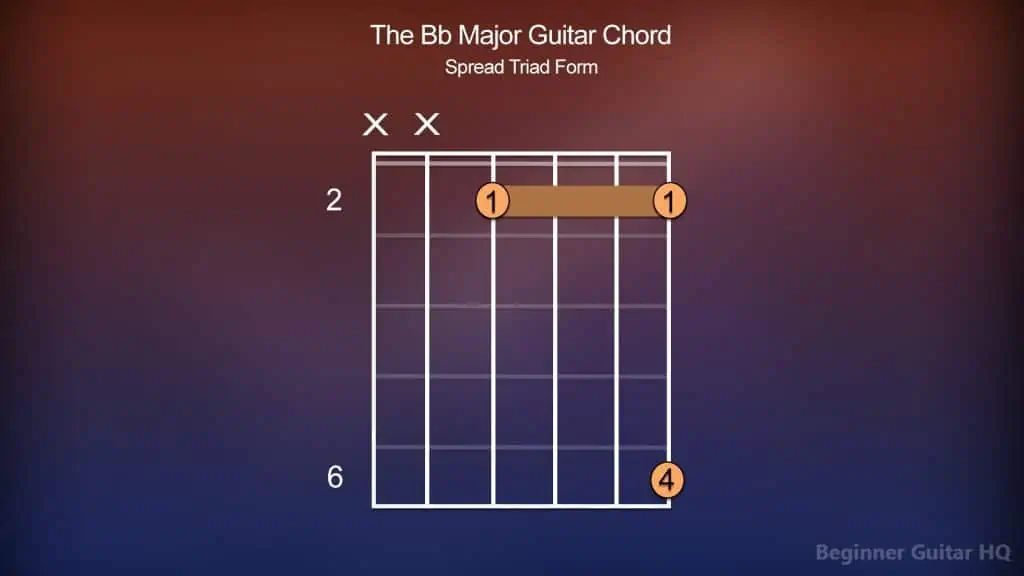

This is another variation of the Bb Major chord in a spread triad form, which is slightly more difficult and uncomfortable for beginners but sounds unique compared to the other variations displayed prior to this one:

Bb Major chord chart in spread triad form.

B Major VS Bb Major

Bb Major, as mentioned has two flats in its key signature, which are B and E. What about B Major? If we can remember the number 7, then we can use this as a tool to figure out the other half of the circle of fifths. If we take the two flats from Bb Major, and then add five, we will have the number 7. Therefore, the key of B Major has five sharps.

If we use the other method of remembering the notes affected by the key signature: FCGDAEB – Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle, then we will have the sharps F, C, G, D, and A.

The key signature will make our B Major scale look like this:

B > C# > D# > E > F# > G# > A# > B

What you will notice is that our scale conforms to the formula used for Major scales (T – T – S – T – T – T – S).

From this information and what we have covered on triads earlier, we can now see that the B Major triad is formed from B, D#, and F#.

Relative Minor of the Bb Chord

Minor keys are the other side of the same coin as our Major keys. When it comes to our circle of fifths, the starting point for our Major keys is C, as it has no sharps or flats. However, when it comes to the Minor keys and the circle of fifths, the starting point is A. This is what’s known as a relative minor, which is something that shares the same key signature but has a different root note.

Essentially the layout is the exact same as our Major keys, however, our root notes are set back by two notes, or forward by 6 notes. Either way, you get the same result.

If we look at the circle of fifths, we can see that the relative minor to our Bb Major is G minor, as they both share two flats in their key signature, which are B and E.

Minor chords still contain triads, however, the pattern within the minor scale is slightly different than that of our Major scale. The pattern follows this sequence of tones (T) and semitones (S):

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

If we reflect our G minor key signature on the scale, it would reflect the minor scale pattern and appear as so:

G > A > Bb > C > D > Eb > F > G

If we tie in the triad to build our chord, we would have G, Bb, and D (tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees) to build our triad.

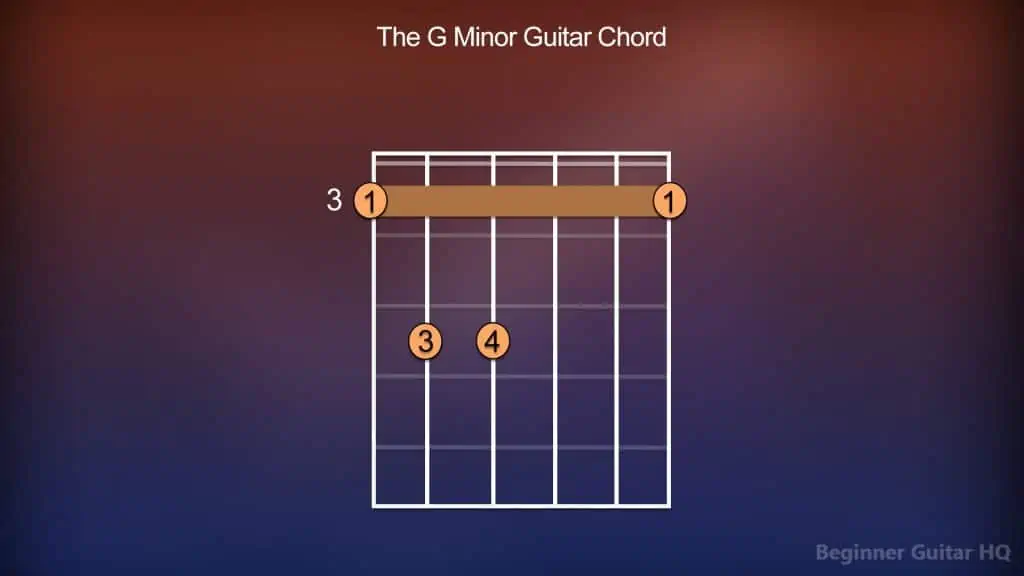

Ultimately, our G minor chord would look like this, giving it a somewhat open, yet melancholy feeling:

Chord diagram, displaying how to play the G minor guitar chord on the third fret.

Scale Degrees and Intervals

Each of the seven degrees within our diatonic scale has an important role in giving us the sound we are searching for, and maintaining a flow that tells a story and sounds pleasant to the ear.

Diagram displaying all of the scale degrees within the C Major Scale (a diatonic scale).

First, we have our tonic, which is our root. This can be helpful for releasing tension and returning to a place of familiarity. It is also the foundation we build our triads, which helps us make chords.

The second degree is the supertonic; in Latin super translates to above as it is just above our tonic. The interval from the tonic to the supertonic is a Major/minor 2nd (M2, m2). This degree is excellent for making extending chords like the 9th chord, or forming conjunct melodic phrases.

Now we’re on to the third degree, the mediant. This is given its name from being in the “middle” of the tonic and dominant degrees of the scale. The interval from the tonic to the mediant is a Major/minor 3rd (M3, m3). It also happens to be the second note used in our triads for Major and minor chords. The mediant is also great as a transitional chord to something more prominent like the subdominant, but can also add some character to a chord progression.

In the fourth degree, the subdominant (sub meaning “below”), is what creates the perfect 4th (P4) interval, however, inverted it is a generic 5th to the tonic. The subdominant is a good chord to bridge between additional tension or resolve. You’ll find that the (I – IV – V) degrees are often used together in different sequences.

The fifth degree is the dominant and is the final piece of our Major and minor triads. The interval between our tonic and dominant is a perfect 5th (P5). Dominant chords may also come in the form of dominant sevenths, and extended dominant chords, which can involve intervals such as ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths. These chords are often used to build on the tension until it’s released by the tonic.

The sixth degree is our submediant, named due to it being between the tonic (octave higher) and the subdominant. Our interval from the tonic to the submediant is a Major/minor 6th (M6/m6). The feeling from our tonic to submediant is similar to that of our tonic to the mediant. It doesn’t create a lot of tension, but it’s great for bridging to the tonic or dominant.

The seventh degree is our leading tone, half a step below the tonic. The interval between our tonic and our leading tone is a Major/minor 7th (M7, m7). Within our Major/minor scales, this degree calls for resolution, as it builds tension right before returning to the tonic.

After all seven degrees have been played, we’re right back at the tonic once again, a whole octave higher.

Learning about scale degrees can be fascinating. For instance, the Nashville Number System is built around this concept and helps musicians figure out how to play different chord progressions on the fly using numbers. This provides musicians some flexibility in being able to change the key they are playing in to accommodate the singer or producer if you’re in the process of recording.

Intervals

The following songs are related to the intervals we had gone over, which can be helpful as a reference.

- m2 – Jaws Theme

- M2 – Happy Birthday

- m3 – Greensleeves

- M3 – When the Saints Go Marching In

- P4 – Here Comes the Bride

- P5 – Star Wars Overture

- m6 – The Entertainer

- M6 – My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean

- m7 – Pure Imagination – Willie Wonka & The Chocolate Factory

- M7 – Somewhere Over the Rainbow

Conclusion

There is a lot more than meets the eye when it comes to music theory, but understanding the fundamentals and being able to build chords on the fly is an asset to every musician. The Bb Major chord might feel challenging at first, but remember to take things slow, and most importantly, be patient and don’t get discouraged! Let’s get playing!