Have you been searching for the right transitional chord to give a feeling of “space” or “openness”? Then look no further than your sus chords. In fact, your Dsus2 chord has been used in many popular songs, such as John Mayer’s hit Free Fallin’, Bryan Adams – Summer of ‘69, The Beatles – Ticket to Ride, and more! Let’s learn more about this great chord, and how you can start using it today.

Contents

How to Play the Dsus2 Chord

Let’s dive right into it and get started with learning how to play your Dsus2 chord. If you already know how to play a D major chord, then this should be a very easy task. If you’re still new to chords, don’t fret, because this is a very easy chord to get down. Here’s how it’s played:

A chord chart of the Dsus2 chord in open note position.

A chord chart of the Dsus2 chord in the 2nd fret position.

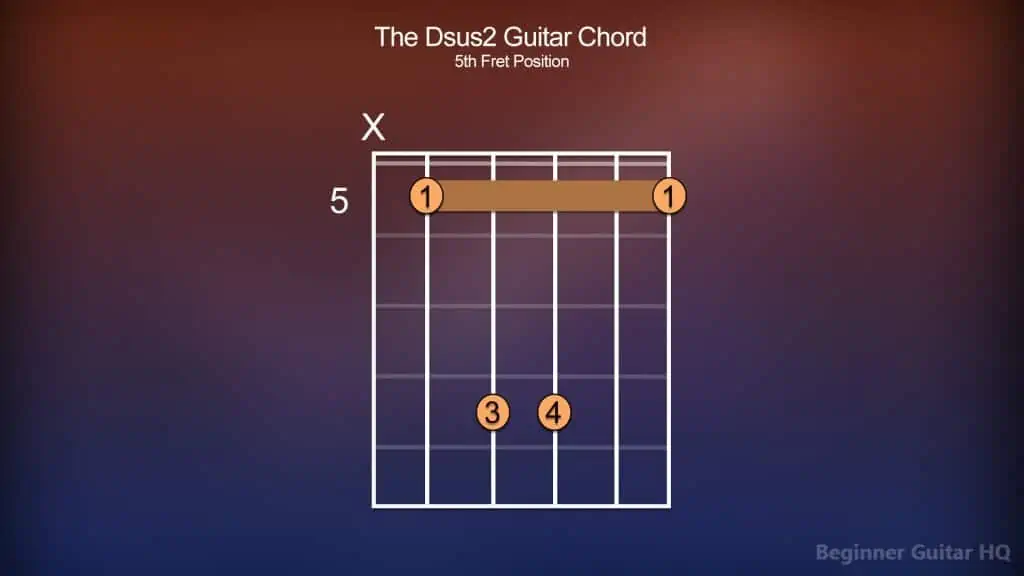

A chord chart of the Dsus2 chord in the 5th fret position.

Trouble With Chord Charts?

If you’ve never seen a chord chart before it might look somewhat intimidating. However, they are actually very easy to learn! First, you’ll see a big rectangular box with a few vertical lines in the middle. Each one of these lines is meant to represent a different string. From left to right, you have your low E string, A, D, G, B, and high E strings. The horizontal lines, however, are meant to separate one fret from the next.

Inside these frets, you’ll see a circle with a number. This is to help you understand which finger is meant to go where, as each number represents a different finger. First, you have the number “1” for your index finger. The number “2” is for your middle finger. The number “3” is for your ring finger. Finally, the number “4” is for your pinky finger. To the left of the fretboard, you might notice a number, or you might not. If a number is there, that is meant to indicate the fret you are starting on.

You may also see, depending on the chord, above the fretboard an “O” or an “X”. An “O” represents an open note, a string to be played but not fretted. However, if you see an “X” that is a string not meant to be played in order to complete the chord.

Breakdown of Dsus2

Let’s first establish what a sus chord actually is. Sus, short for a suspended chord, is commonly used as a transitional chord. The way this often works is when you’re at the peak of your tension in a piece of music, the ears will naturally wait for its resolve. However, in some cases, a sus chord will be inserted before building tension, therefore suspending and drawing out the tonic. Classical music often makes use of these chords for this very purpose. It’s important to note, however, that in modern music this isn’t always the case.

Now, if we take a chord, D major for instance, and we wanted to convert it into a sus chord, we would take the major or minor 3rd interval within our triad and change that interval to a major 2nd or a perfect 4th. In other words, we would be changing the 2nd note of our triad, which is the 3rd degree of our D major scale.

The absence of our typical major/minor 3rd interval creates a sense of openness within our chord. If we changed the major/minor 3rd to a major 2nd, we would get a Dsus2 chord. However, if we changed our major/minor 3rd to a perfect 4th, we would get a Dsus4 chord. You may choose to remember the name of the chord, whether it’s 2 or 4 by the interval used in place of the major 3rd. You may also choose to remember it for which degree on our scale it becomes.

D Major

Since now we understand what makes a Dsus2 chord what it is, let’s talk a little more about the D major chord. Three important factors that make up the D major chord include the key signature, scale, and the triad.

Key Signature

In order to find the key signature of a given key, we should consult the circle of fifths. The circle of fifths is a helpful diagram that displays all of the most commonly used key signatures and their corresponding keys major and minor keys.

A diagram of the circle of fifths displaying all the most commonly used key signatures.

The outer ring contains all of our various major keys, while the inner ring contains all of our relative minor keys (keys that share the same key signature as their major counterpart). To the side of each of these keys, you’ll see some #s (sharps) or b’s (flats) over some lines of sheet music. The #s represent a note that is to be raised by a semitone, while the b’s represent a note that is to be lowered by a semitone. Starting from C major, as you go clockwise around the ring, you’ll notice that each key gains an additional sharp, and as you go counterclockwise around the ring, each note gains an additional flat. For this key, however, we’ll only be focusing on the sharps.

So, how are these sharps determined?

Starting from C major, having no sharps and no flats, moving to G major, we have our first sharp being F sharp. As we move clockwise we now hit the key of D major, with the sharps F, and C sharp. Moving again, we’re on the key of A major, with the sharps F, C, and G. Are you seeing a pattern yet? Between the last sharp added to the key signature to the next sharp added, we have an interval of 5 notes. F > C, C > G, and so on… However, not everyone wants to remember the sequence this way. Thankfully, there is an easier method using the acronym, FCGDAEB. This stands for:

“Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle”.

Each first letter within each word of this little saying represents a different note to be sharp. Here is how the sequence looks:

C = No sharps and no flats

G = F

D = F, C

A = F, C, G

E = F, C, G, D

B = F, C, G, D, A

F# = F, C, G, D, A, E

C# = F, C, G, D, A, E, B

Aside from this saying, the only other thing you are required to remember is the major keys on the right half of our circle of fifths, which can be done by using your fingers! In fact, the notes on the circle of fifths follow the same pattern used to determine the sharps added to the key as they too are 5 notes apart. As you get used to this sequence you’ll know the number of sharps in each of these keys. You’ll know that D major has two sharps, so as you’re counting with your fingers, “Father, Charles..” the sharps are F and C sharp.

There are so many patterns used in music, memorizing them can make your job as a musician that much easier.

D Major Scale

We now have our key signature, which makes determining the notes in our scale much easier. Sharps determine which notes are to be raised a semitone, however, as for the notes that aren’t included in the key signature, they remain the same. Our D major scale follows the sequence of notes:

D > E > F# > G > A > B > C# > D

Major scales have a set pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) that they follow. This sequence looks like this:

T > T > S > T > T > T > S

As you can see from the above D major scale, it follows the sequence of tones and semitones to a tee. E > F is normally a semitone apart, but as the key signature calls for an F#, this now becomes a tone apart, bringing it closer to G, where they are now a semitone apart. The same occurs for B > C#, making it a semitone apart from D.

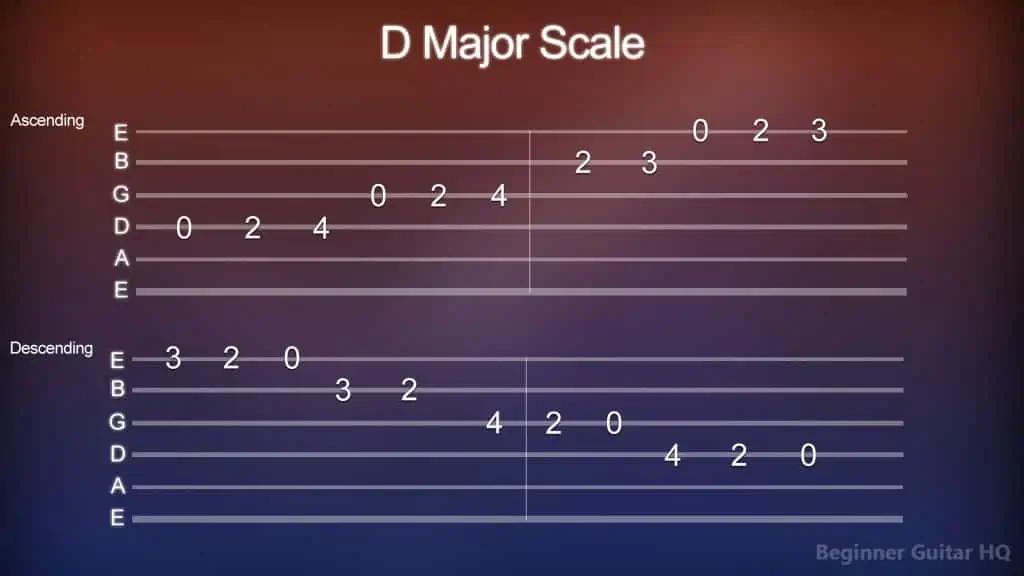

If you wanted to try hearing how the D major scale sounds on the guitar, here is how you can play it using tablature:

Guitar tab of the D major scale

Trouble With Tablature?

Reading tablature, also known as “tab” is very simple! In fact, you can say it was made as a more simplified version of your standard sheet music made primarily for your guitar. As you can see, there are six horizontal lines with a corresponding note, indicating which string it belongs to. From the bottom, upward, you have your low E string, followed by the A, D, G, B, and high E strings.

Each number represents the fret that is to be played on the corresponding string. So for instance, if you have the number “2” on your D string, that means you are to play the second fret of the D string. If you have the number “4” on your G string, then that indicates you are to play the fourth fret of your G string, and so on. When we have a number “0”, that indicates that it’s an open note (in other words a string to be played, but not fretted). That’s all there is to it!

It’s important to know, however, simple as tablature might be, there are some drawbacks. Unlike sheet music, there isn’t that much detail or instruction on how things are intended to be played. In fact, it’s up to you as a guitarist to use your ear to gain a further understanding of how things are meant to be played. This can include hammer-ons/pull-offs, dynamics, BPM, muted notes… etc. If you are lucky, however, some websites providing tablature for you to learn your favorite songs will use other means to supply that information. Here’s an example:

H = Hammer-on

P = Pull-off

B = Bend

X = Mute

PM = Palm Mute

\ = Slide Down

/ = Slide Up

~~~ = Vibrato

Another thing to keep in mind when reading any kind of sheet music is fingering habits. Always plan ahead of where your fingers should be to make playing much easier. For instance, in our D Major scale, the highest fret we will reach is the fourth, therefore, that’s probably a good place for our pinky finger to be. That means, your index should be on the first fret, your middle finger on the second fret, and your ring finger on the third fret. Sheet music won’t typically supply you with this information, therefore, it’s best to develop these habits on your own!

Scale Degrees

Every note within our diatonic scale (any heptatonic scale containing five tones and two semitones) has a name for each corresponding note. These are otherwise known as scale degrees. Each of these scale degrees serves its own important purpose, which we will touch on later. However, within our D major scale, it appears as this:

D = Tonic (1st Degree)

E = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

F# = Mediant (3rd Degree)

G = Subdominant (4th Degree)

A = Dominant (5th Degree)

B = Submediant (6th Degree)

C# = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

D = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

Triads

Now that we have our scale and scale degrees defined, let’s go into what makes up our D major chord, the D major triad. A major triad is a chord made up of three notes played in combination. These notes fall on the 1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees of our scale. For our D major scale, these notes would be D, F#, and A. When played together, you get a D major triad.

Major triads all share the same intervals (an interval being the distance between two notes):

- Major 3rd (Between the 1st and 3rd degrees = D > F#)

- minor 3rd (Between the 3rd and 5th degrees = F# > A)

- Perfect 5th (Between the 1st and 5th degrees = D > A)

These are the notes forming the foundation used within our D major chord. However, this differs slightly when forming a suspended 2nd triad in which it becomes a major 2nd between the tonic, and supertonic (the 1st and 2nd degrees), making the notes D, E, and A to form our triad.

Finding Compatible Chords With D Major

Now, that you know how to find the triad belonging to the key of D major, you may use this same method to find the other chords compatible with the D major chord. Confused how? Let’s walk through it. First, we will form a triad on each note of our D major scale:

D Major = D, F#, A

E minor = E, G, B

F# minor = F#, A, C#

G Major = G, B, D

A Major = A, C#, E

B minor = B, D, F#

C# diminished = C#, E, G

These triads are the foundation for compatible chords with our D major chord. However, one thing isn’t completely clear… how do you know which ones to play? This is where scale degrees come in:

D Major = (Tonic/1st Degree)

E minor = (Supertonic/2nd Degree)

F# minor = (Mediant/3rd Degree)

G Major = (Subdominant/4th Degree)

A Major = (Dominant/5th Degree)

B minor = (Submediant/6th Degree)

C# diminished = (Leading Tone/ 7th Degree)

Each scale degree serves its own purpose as we touched on earlier. Our tonic is our home, providing a sense of calm and resolve. Our supertonic, above the tonic, shares close relations (2 notes) with the subdominant, acting as an optional substitute for it. The mediant, a weaker pre-dominant chord, shares two notes with the tonic, acting as an expansive chord from it. The subdominant, one of the more important degrees applies some tension away from the tonic but typically wants to lead to the dominant. The dominant, which is also important applies the greatest tension, begging for resolve, which tends to lead back to the tonic. The submediant shares two notes with the tonic, making it another great expansive chord from the tonic. Our leading tone holds a lot of tension, being right below the tonic, a very important degree for making 7th chords. Then you’re at the tonic again, one octave higher.

Based on what we’ve covered here, there are some tried and true chord progressions that many artists incorporate using these different scale degrees. Here are just a few of them in D major:

First, we have the I – IV – V progression, which is one of the more popular, yet simple chord progressions to get you started. It incorporates the chords D major, G major, and A major. It will begin on our tonic, which is our home, the root of our key. From our tonic, we will move to our subdominant, and this adds a little bit of tension. Our subdominant shares a note with our tonic, the D. As we move away from it, we add even greater tension, falling on the dominant. Our dominant shares one note with our tonic, the A, but not the D, the center of our tonic. Finally, at the peak of our tension, we will resolve back on our tonic, repeating our progression of three chords.

For our next chord progression, we have a four-chord progression of I – vi – IV – V. In our key of D major, these chords would be D major, B minor, G major, and A major. We start again on the tonic, our home and tonal center. From our tonic, we will move to the submediant, which happens to be a minor chord. The submediant shares two notes with our tonic, acting as an expansive “pre-dominant chord”. In other words, it’s a chord that comes before our dominant chord to draw out to tonic. From here, you will want to add some tension to the chord progression, so you move to the subdominant. Onward, we move to add even greater tension, the dominant, and wrap things up by returning home to our tonic.

Another four-chord progression consisting of the degrees: I – vi – ii – V. This progression contains the sequence of chords, D major, B minor, E minor, and A major. As per usual, we will start at our tonal center, the tonic. Instead of adding more tension, we will expand on the tonic by moving to the submediant. From the submediant, we will move to our supertonic, E minor, which acts as a substitution for our subdominant chord, sharing two notes with it, G and B. Now we move to our dominant, at the peak of our tension, which begs for resolve. Therefore, we return back home to our tonic.

D Minor

Now that we know quite a bit about D major and the Dsus2 chord, what about its minor counterpart, D minor? As you know by now, minor keys share different key signatures than their parallel major keys. In fact, D minor, relative to F major, only has one flat, B flat. This is easily determined by taking our saying from before, “Father, Charles, Goes, Down, And, Ends, Battle”, and reversing it to:

“Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’, Father”

If you know the right half of our circle of fifths (the side containing the sharps), then you can easily determine its left half. You only need to remember the number “7”. For instance, if we know that D# minor has six sharps, then D minor should have only one flat because when you add them together you get the number seven. Another example you’re probably more familiar with, we’ll look at E major, which contains four sharps. Therefore, Eb major would only have three flats, totaling seven.

When we take the D minor scale, key signature and all, we have a scale that follows this sequence of notes:

D > E > F > G > A > Bb > C > D

Different from our D major scale, our D minor scale has its own patterns of tones (T) and semitones (S):

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

When forming a D minor triad, we would get the notes: D, F, and A. However, when it comes to the intervals used in our minor triad, it differs only slightly from the major.

- minor 3rd (Between the 1st and 3rd degrees = D > F)

- Major 3rd (Between the 3rd and 5th degrees = F > A)

- Perfect 5th (Between the 1st and 5th degrees = D > A)

Do you see the difference? The interval between the 1st and 3rd degrees is an interval of a minor 3rd, while in a major triad, this interval is a major 3rd. Another difference is the interval between the 3rd and 5th degree is a major 3rd, while in a major key it’s a minor 3rd. It’s important to note, however, that converting a D minor triad to a Dsus2 is not any different than converting a major chord to Dsus2. The notes forming the triad are still D, E, and A.

Much like before, to find the chords compatible with D minor, we’ll form triads on every degree of our D minor scale:

D minor = D, F, A (Tonic/1st Degree)

E diminished = E, G, Bb (Supertonic/2nd Degree)

F Major = F, A, C (Mediant/3rd Degree)

G minor = G, Bb, D (Subdominant/4th Degree)

A minor = A, C, E (Dominant/5th Degree)

Bb Major = Bb, D, F (Submediant/6th Degree)

C Major = C, E, G (Leading Tone/7th Degree)

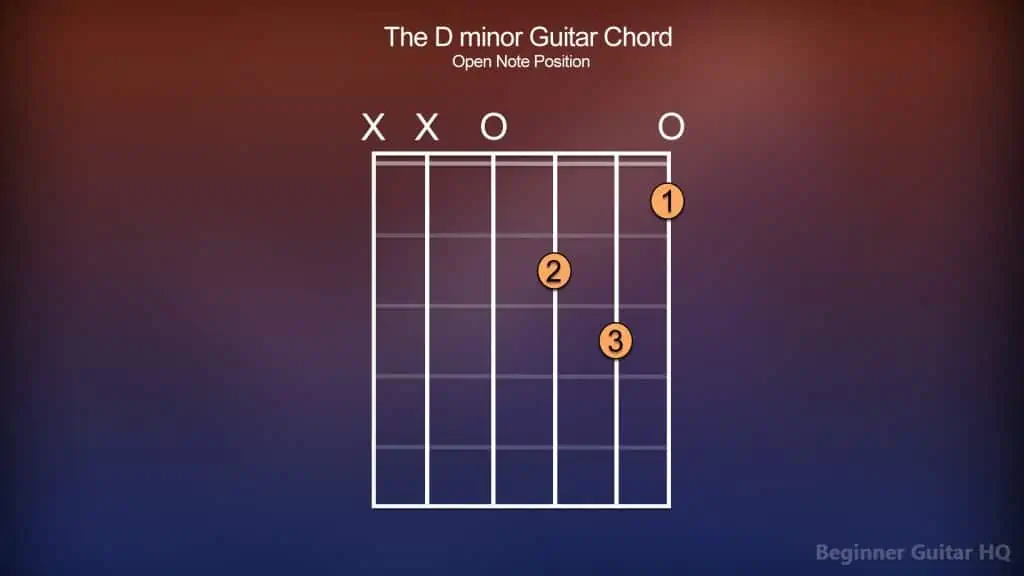

Now, let’s play our D minor chord:

A chord chart of the D minor chord in the open note position.

Conclusion

Now you know everything you need in order to get started with this wonderful suspended chord. It’s very easy to learn, in fact, from the open note position it’s even easier than it is to play your D major chord, requiring less fingerwork. How will you make the most of this nifty chord? Are there any songs that you enjoy that use it? It can be an excellent chord to spice up your progression, so make sure you use it well and keep on rockin’.