If you want to add some nice color and variation to your chord progressions, look no further than your seventh chords. In fact, we’re going to go over a particular type of seventh chord; a dominant seventh chord, F7. As you read on, we’ll cover how you can start playing this chord, and some music theory behind how it works so you can make the most of it today. Let’s dive in!

Contents

How to Play the F7 Chord

The beautiful thing about learning chords on the guitar is the discovery that they can be played in several different ways! We call these chord variations. Chord variations can come in handy for several different reasons. The first reason is for playability – how well it fits into the chord progression, and how easy it makes it for you, the guitarist, to fit it in with the other chords. For instance, if you have a bunch of chords near the open note position, why play a chord that jumps to the eighth fret? It might not always make the most sense!

The second reason, aside from playability, is your playing ability! Some chords might feel a little awkward, or uncomfortable, like our dreaded “barre chords”. In this case, you might opt for a more simplistic version of the same chord.

The third reason is that while these chords may be the same, they may have slightly altered voicings within the chord. Depending on this factor, you might choose one chord over another, based on how it sounds and brings out slightly different colors within the chord progression. If you really want to explore this concept, the CAGED system is a great place to start!

Finally, it can all just come down to personal preference. We all have our favorite chords, which may depend on any of the factors mentioned prior. There really are no right or wrong answers. It’s important to find what works best for you!

Now, let’s take a look at our F7 chord and its variations:

A chord chart of the F7 Guitar Chord in the first fret position.

A chord chart of the F7 Guitar Chord in the third fret position.

A chord chart of the F7 Guitar Chord in the eighth fret position.

Trouble With Chord Charts?

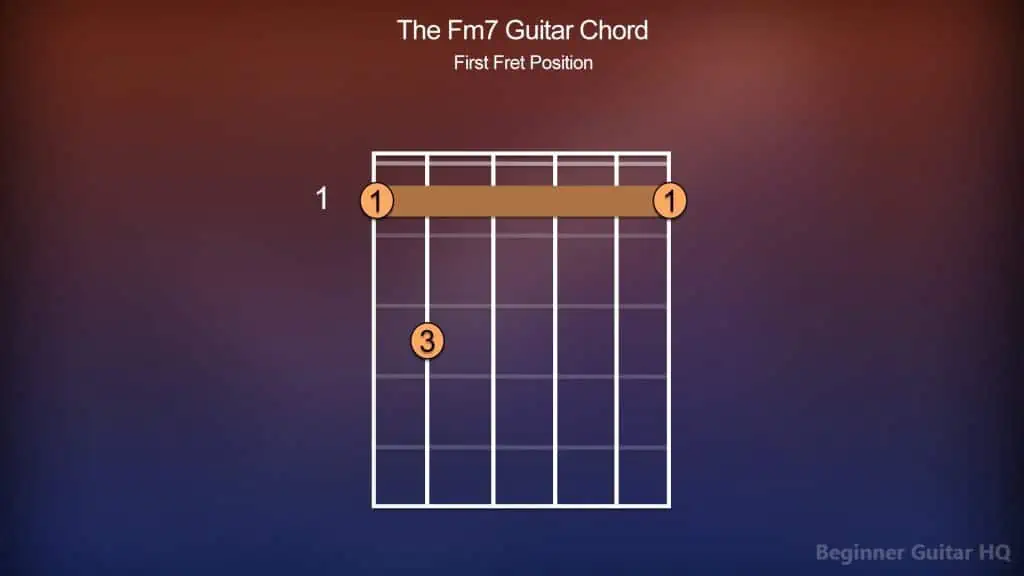

If you’re new to chord charts, it might look somewhat complicated and confusing! Don’t fret. The process of deciphering chord charts is very simple! Let’s first draw our attention to the big rectangular box housing a number of vertical and horizontal lines. Each vertical line represents a different string on the guitar. From left to right, we have our low E, A, D, G, B, and high E strings. The horizontal lines, however, separate one fret from the next.

Next, within the frets, and over the strings, you may notice a circle containing a number anywhere from 1 – 4 inside. These numbers represent your different fingers, and where they’re to be placed on the fretboard to complete our chord. The number 1 represents our index finger. The number 2 represents our middle finger. The number 3 represents our ring finger. Finally, the number 4 represents our pinky finger. You may notice a long dark bar connecting from one number to another, covering a series of strings on a single fret. This indicates you are to form a “barre”, a necessary part of forming a “barre chord”. To achieve this, simply drape your index finger across a grouping of strings on a single fret, and apply pressure.

Atop the fretboard, particularly the strings, you may notice an “O” or an “X”. If an “O” is present, this indicates that you’re to play an open note (a string to be played but not fretted). If, however, there’s an “X”, this indicates that you are not to play the string to complete the chord. Finally, off to the left, beside a fret, there may be a number indicating the starting fret in forming our chord. If, however, there are no numbers present, then it’s generally implied that you’re playing from the open note position.

That’s all there is to it!

Breakdown of the F7 Chord

The F7 chord is what’s known as a dominant seventh chord. Chords like this are often used in blues music, providing a feeling of tension, however, our F7 chord isn’t uncommon in the genres of country, rock, soul, or funk music. So how does a chord like this work? It’s important that we understand a few of the core elements that build our F7 chord: the key, scale, and triad.

Let’s begin with the key. Our key can simply be described as a collection of musical pitches, no different than what you’d find within a scale. How are these musical pitches defined? That’s where our key signature comes into play. Every key has its own key signature. The key signature is visually represented by a collection of sharps (#) and flats (b) often seen after the clef on a piece of sheet music. When a note is marked sharp, it’s to be raised by a semitone. However, when a note is marked flat, it’s to be lowered by a semitone.

So, if we know what our key is, how do we find our key signature? This is where it can help to consult the circle of fifths.

A diagram of the circle of fifths, displaying the most commonly used keys.

The circle of fifths is a wheel-shaped diagram displaying all of our most commonly used keys and their corresponding key signatures. Within the wheel, we have two rings. The outer ring contains our major keys, while the inner ring contains all of our relative minor keys (keys that have a different root note, but contain the same key signature). Starting from C, going clockwise, you’ll notice that every key gains an additional sharp (#) to its key signature. On the other end of the spectrum, starting from C once again, and going counterclockwise, you’ll notice that every key gains an additional flat (b) to its key signature.

Since we are in the key of F major, how can we easily determine which notes are flat? We use the simple acronym of: BEADGCF. This stands for:

“Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’, Father.”

The first letter of each word within this sequence represents a note that is meant to be made flat. For instance, if we were in the key of Bb major, knowing it has 2 flats within its key signature, using our acronym we’d go, “Battle, Ends…” and therefore, our key signature of Bb major contains the two flats Bb, and Eb. Let’s try another example! The key of Gb major contains 6 flats within its key signature. Using our acronym we’d go, “Battle, Ends, And, Down, Goes, Charles’…” therefore, the key signature of Gb major contains the flats, Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, and Cb.

Using this method with our current key, F major, containing 1 flat, we know this key signature only contains Bb.

Let’s take a look at our F major scale, and how the key signature falls into place:

F > G > A > Bb > C > D > E > F

Major scales have a very strict pattern that they all follow, consisting of tones (T) and semitones (S):

T > T > S > T > T > T > S

As you can see, our F major scale follows this pattern to a tee! F > G and G > A are both intervals of a tone apart. The third interval, A > Bb is a semitone apart, thanks to our key signature containing a Bb. The intervals Bb > C, C > D, and D > E are all tones apart, and E > F is a semitone apart. It never fails!

Now, let’s try playing our F major scale:

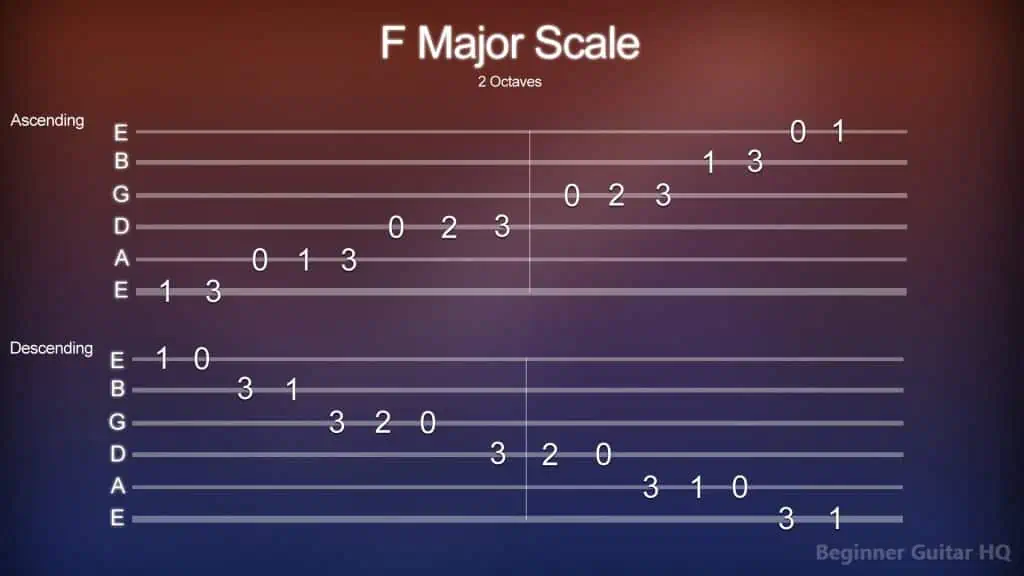

Guitar tablature of the F major scale, ascending and descending from the 1st fret.

Trouble With Tablature?

Guitar tablature, otherwise known as “tab” is a great way for guitarists with no musical background to write, play, and share their favorite songs and exercises. In fact, you may look at it as a more simplified alternative to sheet music/musical notation. Let’s first draw our attention to the six horizontal lines. Each line represents a different string on the guitar. From the bottom to the top we have our low E, A, D, G, B, and high E strings.

On the lines you’ll see different numbers, indicating the fret that’s needed to be played on the corresponding string. For instance, if we see the number 4 on the low E string, then you’re to play the fourth fret of the low E string. If we see the number 2 on the D string, then you’re to play the second fret of the D string. If you see the number 0 on any string, then it’s implied that you’re to play an “open note” (a string to be played but not fretted). That’s all there is to it!

Now, while tablature has a ton of immediate advantages for guitarists who are starting out, it’s fair to say that it comes with a couple of drawbacks. The first drawback is the amount of detail the guitar tab contains. With sheet music, you generally have an abundance of information on how things are meant to be played. So much, in fact, that it can be slightly overwhelming to beginners. Guitar tablature, however, most often doesn’t supply as much information. This means that in a lot of cases, it’s up to you, the guitarist, to use your ear and fill in the gaps. This isn’t to say that guitar tablature shouldn’t be used. It’s important to note that the quality of the guitar tab varies from tab to tab. In fact, here are some known symbols used on tablature to supply this extra bit of detail:

H = Hammer-on

P = Pull-off

B = Bend

X = Mute

PM = Palm Mute

\ = Slide Down

/ = Slide Up

~~~ = Vibrato

Another thing, especially for beginners, to keep in mind is proper playing technique. The proper playing technique we’re referring to here is fingerwork. Guitar tablature, and most often sheet music won’t supply you with information on where your fingers should go. Fingerwork is something that is often left out, because it’s generally implied that you already know, or can figure it out. Furthermore, this makes fingerwork a common pitfall for beginners, developing sloppy playing technique overall. It’s important to combat sloppy playing technique by reading ahead of what you’re about to play and finding a comfortable place for your hand to be situated. The general idea is you want the notes to fit within the space of your hand, whilst having your fingers come down directly on the strings. You don’t want a whole lot of movement, but to maintain the same shape with your hand, keeping things nice and loose.

Scale Degrees

We now know the notes contained within our F major scale – but did you know that each note within our scale has an important role? We call these notes our various scale degrees. Each scale degree has its own unique name, helping musicians refer back to them with ease. Here are the different scale degrees within the F major scale:

F = Tonic (1st Degree)

G = Supertonic (2nd Degree)

A = Mediant (3rd Degree)

Bb = Subdominant (4th Degree)

C = Dominant (5th Degree)

D = Submediant (6th Degree)

E = Leading Tone (7th Degree)

F = Tonic (1st Degree/Octave)

Let’s talk about each degree’s role a little bit more. Our first degree, the tonic, is our home, our tonal center, where things will come to resolve. The second degree, the supertonic, acts as a predominant degree, as its triad shares two notes with our fourth degree. The third degree, the mediant, shares two notes in its triad with our tonic, making it an excellent degree to draw our tonic out. The fourth degree, the subdominant, is an excellent degree for building a little bit of tension, sharing only but one note, with our tonic triad, F. The fifth degree, the dominant, is our most important degree, next to our tonic. This degree acts as the climax, the great tension-building degree, as naturally, it wants to resolve to our tonic. The sixth degree, the submediant, shares two notes with our subdominant triad, making it another great predominant, tension-building degree. Next, we have our seventh degree, the leading tone. The leading tone serves as a very important degree in building our seventh chords. Furthermore, the leading tone holds a lot of tension – try playing the C major scale and ending on B; your ears will want to hear it resolve to C. Finally, we’re back to our tonic, just one degree higher from where we began.

Triads

A triad is a type of chord built on the foundation of three notes played in unison. An F major triad, in particular, is built from taking the tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees of our F major scale (the 1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees). This gives us the notes: F, A, and C.

When we want to convert our F major triad, to an F7 chord (F dominant seventh chord), we simply take our existing triad of notes (F, A, and C), and stack a flattened seventh degree of our scale on top. This gives us the notes: F, A, C, and Eb in our F7 chord.

Finding Chords Compatible With F Major

Building a chord progression can be a challenge for musicians, let alone one we like! Thankfully, however, there’s a process to making this task just a little easier! To achieve this, we need to make use of our newly learned triads and create one on each degree of our F major scale.

F Major = F, A, C (Tonic/1st Degree)

G minor = G, Bb, D (Supertonic/2nd Degree)

A minor = A, C, E (Mediant/3rd Degree)

Bb Major = Bb, D, F (Subdominant/4th Degree)

C Major = C, E, G (Dominant/5th Degree)

D minor = D, F, A (Submediant/6th Degree)

E Diminished = E, G, Bb (Leading Tone/7th Degree)

Now you have all of the chords you can use in the key of F major! Now, while this might be great to know, you might still feel somewhat stuck in making your own chord progression. In this case, it doesn’t hurt to use some tried and true chord progressions as the foundation for your song! Here are a couple of different examples:

I – IV – V

The one-four-five chord progression is one of the most commonly used chord progressions out there! For this one, we start on the tonic, our home, F major. Things feel relatively calm here. Next, we’ll add some slight tension, moving to our fourth degree, Bb major. The Bb major chord shares one note with our F major chord, the note F. Adding even greater tension, we’ll shift away to our C major chord, sharing a different note in common with our tonic, C. Finally, at the peak of our tension, things call for resolve, therefore, we’ll return home to do it all again, on F major.

Our chord progression looks like this: F > Bb > C

ii – V – I

This chord progression is a slightly more complex, two-five-one turnaround, commonly used in the world of jazz music. For this, we won’t be starting on the tonic, but instead on the supertonic, a G minor seventh chord. We already have some tension, as remember: the supertonic acts as a predominant chord, sharing two notes with our subdominant triad! To shift to even greater tension, we’ll now move to our dominant, C major seventh. Finally, seeking resolve, we’ll shift to the tonic, an F major seventh, not to be confused with our F7 chord as Fmaj7 doesn’t flatten the E.

Our chord progression looks like this: Gm7 > C7 > Fmaj7

F7 to Fm7

Now that we understand quite a bit about the F7 chord, what about its minor counterpart, Fm7? We should first note the relationship between F major, and F minor is a parallel key relationship, meaning that they share the same tonic, but have different key signatures. This is the opposite of a relative key relationship, like F major to D minor, as they both have the same key signature, but contain a different tonic.

So what’s the key signature of F minor?

F minor contains four flats in its key signature: Bb, Eb, Ab, and Db. Understanding the key signature of F minor, let’s put it into scale form:

F > G > Ab > Bb > C > Db > Eb > F

Much like our major scales, minor scales have their own strict pattern of tones (T) and semitones (S) that they always follow:

T > S > T > T > S > T > T

Looking at our scale, we can see the first interval, F > G is a tone apart. The second interval, however, from G > Ab is a semitone apart. The third and fourth intervals, Ab > Bb, and Bb > C are both tones apart. The fifth interval, C > Db is a semitone apart, while the sixth and seventh intervals, Db > Eb, and Eb > F are both tones apart.

Now, let’s create an F minor triad. Just as before, we’ll be taking our tonic, mediant, and dominant degrees of our F minor scale (1st, 3rd, and 5th degrees) and stacking them on top of each other. This gives us the notes: F, Ab, and C.

When converting our Fm chord to an Fm7 chord, we take our seventh degree, Eb, and stack it on top of the other notes, giving us: F, Ab, C, and Eb.

Now, let’s try playing our Fm7 chord:

A chord chart of the Fm7 Guitar Chord in the first fret position.

Conclusion

Now you know everything you need in order to get started with the F7 chord! Seventh chords can bring a lot of value to not just songwriting, but building your skills as a musician in general. However, why stop there!? There are 9th, 11th, and even 13th chords. You even have diminished, augmented, suspended… the list goes on! It’s important to keep things fresh, and always find ways of challenging yourself on the guitar. Because, after all, you’re here to have fun! So what will you do with this newfound knowledge? Wherever your endeavors take you, keep on rockin’!